Continuous Integration

The use of COBOL cripples the mind; its teaching should, therefore, be regarded as a criminal offense.

--Edsger Dijkstra

Continuous integration (CI) is essential for scaling lean and agile development:

Our conclusion is that there is no inherent reason why Continuous Integration and Automated Build processes won’t scale to any size team. In fact… [they] become more essential than ever. Magennis07

With CI, developers gradually grow a stable system by working in small batches and short cycles–a lean theme. This enables teams to work on shared code and increases the visibility into the development and quality of the system.

There are misconceptions about CI; it seems a simple concept, but in practice it’s not. To get one misconception out of the way: Continuous integration is not automating the build and running tests .

The classic paper on CI states:

Continuous Integration is a software development practice where members of a team integrate their work frequently, usually each person integrates at least daily - leading to multiple integrations per day. Each integration is verified by an automated build (including test) to detect integration errors as quickly as possible.

Continuous Integration Practices

Continuous Integration is:

- a developer practice…

- to keep a working system

- by small changes

- growing the system

- by integrating at least daily

- on the mainline

- supported by a CI system

- with lots of automated tests

Developer Practice

Discussions about CI all too often are about tools and automation. Though important, CI in essence is a developer practice. Owen Rogers, one of the original creators of CruiseControl.NET1 writes:

Continuous integration is a practice–it is about what people do, not about what tools they use. As a project starts to scale, it is easy to be deceived into thinking that the team is practicing continuous integration just because all of the tools are set up and running. If developers do not have the discipline to integrate their changes on a regular basis or to maintain the integration environment in a good working order they are not practicing continuous integration. Full stop. [Rogers04]

Splitting changes into small increments, integrating them at least daily, and having the discipline to not break the build are all done by the individual developer. He needs the skill to work in small increments and keep his own copy of the system (or part of the system) working all the time.

Adopting CI requires a change in human behavior . We worked with several large products with an excellent automated build but where developers did not integrate their code frequently. Even worse, the message “thou shall not break the build” was strongly promoted, for example, by shaming the people who broke the build. The predictable result? Developers would delay their integrations out of fear of breaking the build. Despite their excellent always-green (always passing) automated build, they are doing the opposite of CI.

Test-driven development (TDD) with constant refactoring helps. When a developer is unit-test-driving his code, he ensures that his local copy is always working. All the tests pass all the time. In theory, he is able to integrate code every TDD cycle (about ten minutes2); in practice, he integrates after a couple of cycles.

CI on large products is hard precisely because it is a developer practice. If it were only about tools and automation, you could simply start a CI project or hire a company to “install CI.” But as a developer practice, CI requires a change to the daily habits of all developers. With many people, this is hard, takes time, and requires coaching.

With the right behavior, the developers will…

Keep a Working System

Similar to the lean concept of jidoka , CI means always having a stable system. When a test fails–run locally or on the CI system–the developer fixes it immediately and therefore always keeps a working and stable system.

Traditional sequential development has un-integrated work-in-progress (WIP). Nobody knows if these parts work together or if they are free of defects. WIP makes it hard to predict when, or if, the system is deliverable. CI increases visibility by removing this WIP–always having everything integrated–and with this comes more control and predictability.

Note : CI and iterative and incremental development in Scrum have the same strategy. However, CI is a more fine-grained level than a Scrum iteration. Both reduce variability, uncertainty, and risk by working in small batches--iteratively.

This working system, evolved in small increments, is created by…

Small Changes

We once worked with a gateway product group in Finland who needed to make a change to their protocol stack. They insisted it could not be split into small changes. They made the large change and spent three months trying to get the system to work again. After that painful experience, they agreed to never make such large changes in one big batch.

Large changes to a stable system will destabilize and break it in large ways . The larger the change, the more time it takes to get the system back to a stable state.

Avoid large changes. Instead, break each change into small changes–the lean concept small batches. Each change integrates in the system easily.

By small changes you will be…

Growing the System

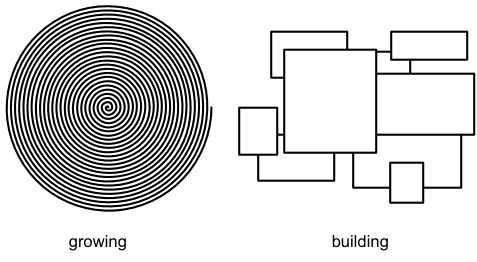

Growing versus building is an important mindset shift. Brooks, in his famous article, No Silver Bullet , reflects on his experience:

The building metaphor has outlived its usefulness… If, as I believe, the conceptual structures we construct today are too complicated to be accurately specified in advance, and too complex to be built faultlessly, then we must take a radically different approach… The secret is that it is grown, not built… Harlan Mills proposed that any software system should be grown by incremental development… Nothing in the past decade has so radically changed my own practice, or its effectiveness… The morale effects are startling. Enthusiasm jumps when there is a running system, even a simple one… One always has, at every stage in the process, a running system. I find that teams can grow much more complex entities in four months than they can build.

Building a system implies building separate components and, when they are finished, assembling them together. Growing a system implies nurturing it and evolving it into a larger system (See grow-ing versus building.).

Is this possible in big systems with legacy code? We get that question frequently. In almost every case, the answer is yes . If your developers or architects cannot do this or claim it is not possible, take that as a sign of lack of skill.

A developer continuously integrates his work while working on a task. He does not wait for the task or the whole feature to be complete and then “bolt it” on the system. Rather, whenever a small amount of work can be integrated without breaking the system, then he integrates it…

At Least Daily

How frequent is ‘continuous’? As frequently as possible! This is limited by

- the ability to split large changes

- speed of integration

- speed of feedback cycle

Ability to split large changes –splitting large changes into smaller ones, while keeping the old functionality working, is a skill that must be learned. The better developers are at this splitting, the more frequently they can integrate. TDD, in short ten-minute cycles, is an excellent technique for this.

Speed of integration –the more time it takes to integrate changes into the code repository, the less frequently developers will do so. Changes are batched for the sake of efficiency. Integration effort is impacted by the process overhead (the transaction cost), such as approvals and reviews needed before developers are allowed to integrate. Reduce this overhead or find creative ways to do things differently. For example, we worked with a 40-person product group where the check-in message had to mention the person who had reviewed the code. The result? Developers batched many changes to make the code reviews more ‘effective’ and thus delayed integration–a local optimization. Solution? Code reviews can instead be done on already integrated code–not delaying the integration.

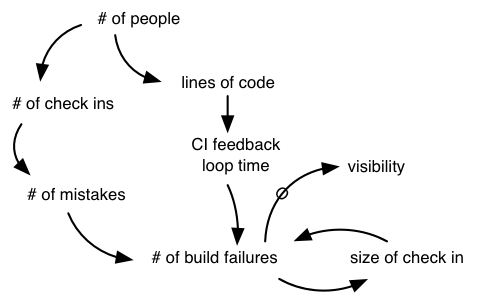

Speed of feedback cycle –a developer should only integrate changes that do not break existing tests. Ideally, he runs all the tests before integrating. For this to be possible, the tests must run very fast. If they are slow, the developer will delay the integration to “work more efficiently.” However, running all the tests quickly is hard for large systems. Therefore, developers only run a subset of tests before checking in, and a CI system runs the remaining tests. The CI system acts as a safety net by giving the developer feedback about the tests he did not run. What happens when the CI system is slow? First, there will be many changes during one cycle, increasing the chance the build breaks. Second, developers do not integrate their changes in the broken build; rather, they batch them. Finally, when the build is fixed, all developers integrate their batched changes, leading to a high chance of breaking the build again. Therefore, the safety-net-feedback cycle has to be fast. This decreases the chance the build will break and increases the ability to check in more frequently.

Rule of thumb for large products moving to agile and lean development: All developers integrate at least daily. Even though “daily builds are for wimps ” [Jeffries04], daily is a first step for large products. Recall the “lake and rocks” metaphor used in lean thinking–the big rock of just being able to build once a day with everyone’s updates is hard enough on big old systems with 300 developers in four countries. Eventually, that big rock is removed, and shorter cycles are possible.

On large products, it will take time to learn to split changes, simplify the integration process, and set up a fast CI system running…

On the Mainline

Developers integrate on the mainline or trunk [BA03]. Making changes on a separate branch means that the integration with the main branch is delayed.3 The current status is not visible, so you do not know if everything works together.

Branching during development breaks the purpose of CI and should be avoided. There are exceptions: First, customers might not want to upgrade their product to the latest release but still want patches. Thus, release branches are needed.4 Second, when scaling up a CI system, it can be useful to have very short-lived branches that are automatically integrated in the mainline–more about that later.

What about branching for customization? Bad idea! Instead, manage these through a configurable design or parameterized build instead of using your Software Configuration Management (SCM) system. We once worked on a network-optimizing product being built by a co-located product group who insisted on branching for different configurations. Developers worked on these separate branches for over a year. Afterwards, it took them an additional half-year –and lots of fighting–to merge them in the trunk.

Successful mainline development is…

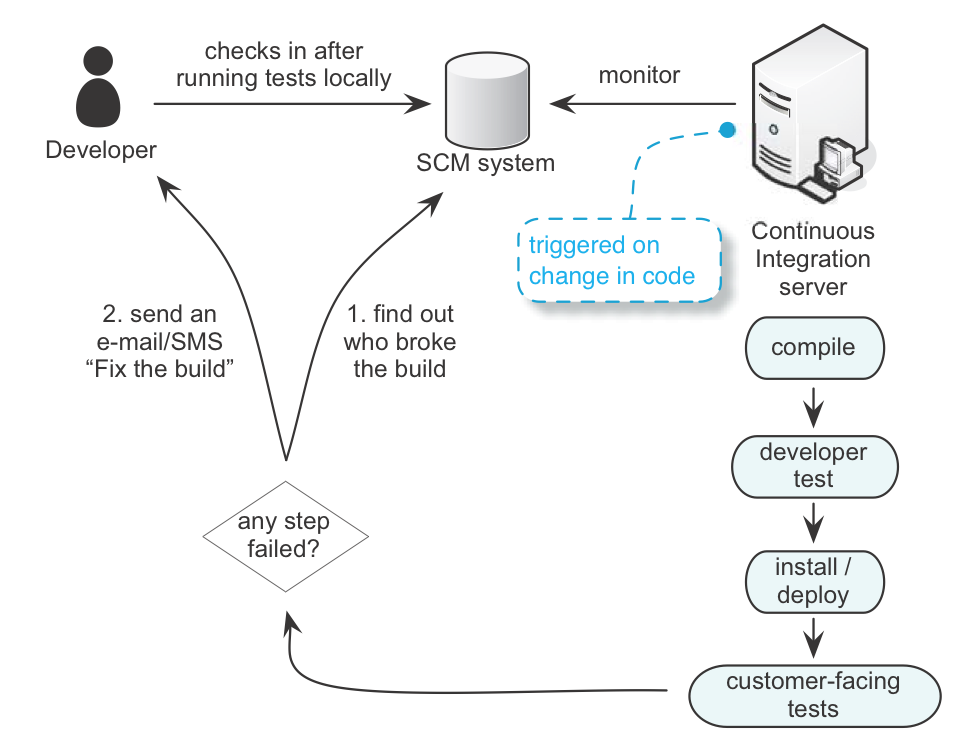

Supported by a CI System

Lean emphasizes minimizing inventory–one type of waste. Inventory acts as a buffer (another queue) in which mistakes are hidden. Mistakes become painfully visible when these buffers are removed–and that is a good thing. The same thing happens when all changes are integrated directly to the mainline. All developers update their local copy frequently; when someone checks in broken code, it is visible to everybody–they will be annoyed.

People make mistakes. That’s OK. A lean stop-the-line safety net is needed to detect them early. Developers fix a mistake before it affects others. This safety net, an andon -like system, in Toyota terminology, is a CI system.

A CI system (See CI system.) listens to the SCM system. When a developer checks in code, the CI system checks out all the code and compiles it, runs some tests, installs it, and runs more tests. All this happens fast; Extreme Programming recommends within ten minutes. If a developer breaks the build, the CI system will query the SCM system and find out who made the change. It sends him e-mail saying: “You broke the build, fix it!” Fixing the broken build is the number one priority because it affects everybody.

For a small product, it is easy to have a fast, ten-minute build. For a large product with legacy code and many people, it is quite a challenge. Later, this chapter examines several techniques for scaling up a CI system…

With Lots of Automated Tests

It is not very hard to have a CI system compile everything; it’s not very useful either. You want to have as many tests as possible running in your CI system. The more automated tests, the better your safety net and the more confidence your system is working.

For new products, creating automated tests is not hard. However, many large products have legacy code without automated tests. Developers need to add automated tests–which is a lot of work. The chapter on legacy code covers this.

Scaling a CI System

First, the build and test need to be fully automated. Many large products groups we worked with have manual steps in their build. See the recommended readings for texts that are useful for automating the build.

The obstacles for scaling a CI system relate to more people producing more code and tests. First, the probability of breaking the build increases with more people checking in code. Second, an increase in code size leads to a slower build and thus a slower CI feedback loop. These together can lead to continuous build failure (See the dynamics of broken builds.).

The solutions are simple:

- speed up the build

- implement a multi-stage CI system

Job one: Speed up the build. If the whole product can be compiled and tested within one second , then scaling techniques are not needed. The one-second build is out of reach for large products, for now . Though every improvement brings us closer, the one-second build helps. Giving general guidelines for speeding up builds is hard–it’s often product specific. Some general solutions [Rasmusson04]:

- add hardware

- parallelize

- change tools

- build incrementally

- deploy incrementally

- manage dependencies

- refactor tests

Add hardware –the easiest way to speed up the build is to buy more hardware. Throw a couple of extra computers, extra memory, or a faster network connection at the problem and it goes away. Upgrading existing hardware takes investment and only minimum effort, making it the easiest and best choice. The build of one telecom product speeded up 50 percent by compilation on a RAM disk–and this only required a memory upgrade.

Parallelize –related to adding hardware is to parallelize and distribute the build. It often requires redesigning the build scripts, changing tools, or even building new tools. Therefore, more effort is needed compared with just adding new hardware. A large telecom product speeded up their build by building every component on a separate computer.

Change tools –upgrading tools to the latest version or replacing a slow tool with a fast one speeds up the build a lot. Simply by switching compilers we once made a 50 percent improvement in compile time. The most common problematic, slow tool we see used is IBM Rational ClearCase. Every time a product group switched from ClearCase to Subversion–a good free open-source SCM system–they… First, speeded up the build (our clients have seen 25%-50% improvement); Second, saved the company significant money by eliminating licenses; And third, improved the lives of the developers, since ClearCase is often the most hated development tool in the groups we work with. Some misinformed people incorrectly argue that Subversion is not suitable for large-product development. But we have seen it used successfully in product groups with four hundred people located at multiple sites around the globe. Ironically, the so-called large-scale features of ClearCase, such as multisite support, make real CI impossible because they force code ownership.

Build incrementally –you only need to compile changed components and run related tests. Easy in theory; hard in practice. Dependencies between components, changes in interfaces, or incompatible binaries are some of the things that make compiling only the change a difficult proposition. For the same reasons, finding all tests related to the changed component can be difficult. Incremental builds are rarely 100 percent reliable, and to prevent corruption of the incremental build, it’s a good idea to also keep a clean daily build.

Deploy incrementally –on large embedded products, it can take a long time to deploy or install software; a radio network’s telecom product we worked with took more than an hour to deploy. This is not unusual. Testing speeds up when the deployment is done incrementally–only the changed components are deployed. The changes need to be loaded, and this can be done by rebooting the system. However, starting a large system is time consuming, and therefore some systems are upgraded dynamically–an important feature in telecom and other industries where downtime is very expensive. Incremental deployment–especially dynamic upgrading–requires changes to the system, making this option difficult.

Manage dependencies –unmanaged dependencies are a common reason for slow builds. Examples: Header files including many other header files, or multiple link cycles to resolve cyclic link dependencies. For a multimedia product, we spent several hours on re-ordering link dependencies–cutting link time in half. Reducing dependencies speeds up your build and, as a side effect, improves the structure of your product.

- Note a key insight

- Improving the build improves the structure of your product. Why? Because bad structure becomes painfully visible when you try to shorten the cycle time of the build.

This is a lean insight discussed before: A powerful side effect of shorter cycle times is the need to dramatically improve the processes and the product to support short cycles and small batches.

Refactor tests –unfortunately, many developers care less about test code than production code. The result? Badly structured test code and slow tests. We once spent only half a day refactoring tests–and speeded up the build by 60 percent! By profiling and refactoring tests you can frequently make these kinds of quick gains.

A multi-stage CI system splits the build and executes it in different feedback cycles. At the lowest level, it has a very fast CI build containing unit tests and some functional tests. When this CI build succeeds, it triggers a higher-level build, containing slower system-level tests. Larger products have more stages.

A CI system is comparable to the “stop the line” culture at Toyota. When a defect is detected, Toyota stops the line, and the first priority is to fix the defect and its root cause. Isn’t a multi-stage CI system hiding defects and against this lean principle? No. A stop-the-line attitude is absolutely needed, but this does not mean that you should blindly stop all the work. Even Toyota does not do that [LM06a].

Toyota has developed a system that allows problems to be identified and elevated without necessarily stopping the line. When a problem is identified and the cord is pulled, the alarm sounds and a yellow light is turned on. The line will continue to move until the end of work zone–the “fixed position stop” point… the line will stop when the fixed position is reached and the andon will turn red.

A multi-stage CI system works the same way. You identify the problem early and act on it, but you do not want it to affect everyone. Only if the problem turns out to be really serious do you “stop the line.”

When building a multi-stage CI system, consider

- a developer build

- component or feature focus

- automatic or manual promotion

- event or time triggers

- the number of stages

A developer build –developers practicing CI need to verify their changes before checking in. Therefore, they must be able to work with a subset of the system, often a component, and be able to run unit tests for it. Take this into account when automating your build.

Component or feature focus –a traditional multi-stage CI system is structured around components. The lowest level builds one component, the next level a subsystem, and the highest level builds the whole product. With teams organized around components, the team takes care of “their” CI system [AKB04 (originally at: http://www.cmcrossroads.com/articles/agilemar04.pdf)]. But where to include higher-level acceptance tests, and what about feature teams? An alternative is to structure your CI system around features. When someone checks in code, all the related feature-CI systems are triggered. Tests are now run in parallel, but the same component is compiled multiple times.

One distributed product group we worked with mixes the two approaches. On a lower level, the CI system is organized around components, and the output of this triggers multiple-feature CI systems running higher-level acceptance tests in parallel.

Automatic or manual promotion –letting all stages of a CI system listen to the mainline creates a mess. When a developer makes a mistake, all the stages fail. A higher-level CI system needs to be triggered by an announcement that the component can be used. Such announcement is called a promotion and is done by labeling (or tagging) the component. Promoting a component can be done automatically or manually [Poole08]. With automatic promotion the lower-level CI system promotes a component after it passed. Avoid manual promotion whereby the team decides when the component is “good enough” and promotes it.

Event or time triggers –every CI system is triggered by either an event or by time. The low-level CI systems are always triggered by an event–a code check-in. For higher-level CI systems, the trigger is either the promotion of a component or time. A trigger by promotion is faster, but for slow builds it is not worth the extra effort in configuration and maintenance. A higher-level daily build might be good enough [Vodde08]. For example, one distributed product group we worked with had low-level, code-triggered CI systems, a higher-level promotion-triggered CI system, and a daily build running tests that lasted over eight hours.

The number of stages –the size and ‘legacy-ness’ of the product determine how many levels of CI systems are needed. Common stages are

- fast component-level –a very fast low-level CI system for quick feedback. It runs unit tests, code coverage, static analysis, and complexity measurements.

- slow component-level –a slower low-level CI system. It runs integration or slow component-level tests.

- product stability-level –a very fast product-level CI system for quick feedback on the basic product stability. It runs fast functional tests (smoke tests) .

- feature-level –a slower high-level CI system. It runs functional and acceptance tests.

- system-level –a slow high-level CI system. It runs system-level tests, which often take hours.

- stability-performance-level –a very slow high-level CI system. It continuously runs stability and performance tests, which often take days, if not weeks.

We have yet to see all stages in one product. Most products select stages most important for them and add more stages only when needed. An unnecessarily complex CI system is a waste.

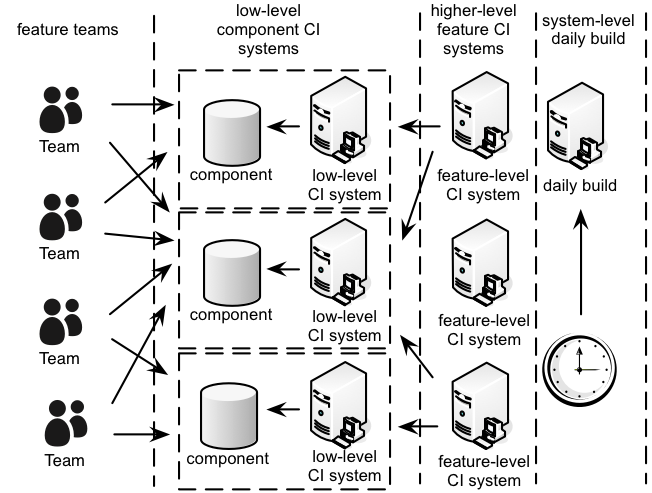

Example Staged-CI System

See scaled CI system. shows an example staged-CI system. In this example, every component has a CI system executing unit tests, plus static analysis and code coverage metrics. A successful build promotes the component and triggers feature-level CI systems executing higher-level tests. A daily build executes system-level tests such as performance tests.

A CI system can effectively include visual management–a lean principle. When the build breaks, a visual signal indicates failure–an andon system (Toyota terminology). The intent is not for managers to punish the developer who broke the build; it is for developers to see the status of the build. What would they do with this information? Investigate what is going on or delay their integration when the build fails. If, after some time, the visual signal still indicates failure, more people may explore why it is not fixed.

A popular early visual tool to plug into a CI system was a lava lamp. A green bubbling lava lamp indicated a passing build. But when the build failed, a red lava lamp started bubbling.

After lava lamps, people started attaching all kinds of displays to the build, such as Christmas lights, sirens, and moving skeletons that screamed when the build broke. Though less entertaining, a simple monitor showing a Web page of a large red or green color blob (a red-green screen ) is more easily reproducible. Red-green screens seem to have become ubiquitous in large-scale CI. Some versions include a yellow signal to indicate “the broken build is now being fixed.” The simple large color blob–visible from a distance–is the key element, but the display can also add text or chart data, such as build duration or test coverage. The information does not need to be limited to build information [Rogers08].

One warning related to visual management, well stated by Jeffrey Liker [LH08]:

Just because there is visual presentation does not mean there is visual management. It is relatively easy to set up nice display areas that are for show. The challenging part is making them “for go.” Many people who visit Toyota openly voice the difference of their approach. We often hear comments such as “Now I see, the things that Toyota displays are actually driving action on a daily basis.” This is indeed the difference, and Toyota would suggest that if it is not driving daily action, get rid of it.

On large products it is even harder to split large changes into small ones. Developers sometimes want to restructure or re-architect their legacy system and are convinced that it must be done in one large change. But we have yet to see a large refactoring that could not be done gradually. Every time, after discussion with the developers, we found ways of splitting the must-be-done-at-once large refactoring [RL06].

Interface changes are a common problem in large systems. Many components use the interface and need to be changed–making it impossible to do gradually, right? Not so. In fact, an interface change in APIs is common, and there is a well-known solution:

Every step can be done independently and at different times. For public APIs, it is impossible to find out if there are still users of the old interface. This makes removing the old interface difficult. But most interfaces are not part of a published API, so do not forget to remove the obsolete one. We have seen many products with three or four file system interfaces or logging interfaces because the old ones were never removed.

Do’s and Don’ts

The previous section alluded to CI do’s and don’ts:

DO commit and integrate every TDD cycle (e.g., every 5 or 10 minutes)—And as hands-on developers ourselves we know that speed is easy with new code, but hard with messy legacy code.

Do NOT develop on branches—If using a distributed tool such as Git, push to the common ‘master’ every TDD cycle.

Do NOT have a policy to review code before commit—If you do that, you will have long-delayed integration creating other big quality problems and many hidden issues! Instead…

DO build quality in to the code to support optimistic integration— How to move from a pessimistic policy of delayed integration after a code review to an optimistic policy of early integration?2 Create a culture of software craftsmanship, TDD and refactoring for clean code, pair or mob programming to review-while-coding, and automated code- checking tools. And if code reviews are still desired, do them on a slower cycle of small batches of already-checked-in code.

Do NOT have a “don’t break the build” policy; and do NOT have blaming and shaming when it breaks—if you do that, it will create fear and avoidance of integration. Then once again, long-delayed integration with many hidden problems. Instead…

DO make it is easy to fail fast, stop & fix, and learn from ‘mistakes’— Create a lighting-fast CI system that gives rapid feedback when the build breaks. Eliminate the barriers that inhibit people from practicing stop and fix. Create an environment of personal safety where people can admit problems and learn to improve.

DO “stop and fix” when the build breaks—“We’re too busy dealing with problems to fix our broken build.” Need to spell it out? Didn’t think so.

DO use visual management showing the state of the build—Install old and unloved computers and monitors ‘everywhere’ to show build state.

Use Feature Toggles

As with continuous integration, feature toggle are often (unfortunately) not seen as a mechanism to support coordination and integration.

A frequent large-group integration-coordination problem is that some teams have added features that are immediately ready for use, and other teams have added features that aren’t ready for prime time and shouldn’t be made visible. This is usually because they aren’t feature-rich enough to be minimally useful. Rather than delay integration by working on a separate branch or not checking in the code, what to do?

Use feature toggles that expose or hide features based on configuration settings, while still integrating continuously across all developers and teams. And for scaling use a free open-source tool such as Togglz.

At the simplest level, a feature toggle is just a conditional statement around code. So why a special tool? What makes tools such as Togglz useful in a scaling context are the administrative features they provide for toggle management of many features in different deployments, such as production versus sandbox.

Conclusion

How to start? Using CI requires

- changing developer behavior

- setting up a CI system

Changing developer behavior –Because large products have many people, this is the hardest task. Focus on TDD–a great way of splitting a large change into smaller ones. Using TDD coaches, who pair-program to teach, is an efficient way of learning TDD. But be patient. TDD is a hard change for most developers and learning takes time.

Setting up a CI system –Most products we worked with set up a separate project for building a CI system. This works, though a better alternative is to add the work to the Product Backlog and let an existing feature team work on it. This creates more visibility and a sense of ownership–the developers are also users.

Most problems implementing CI are organizational and not technical. In many products we worked with, CI became an organizational mess. It involved many traditional functions and roles: developers, managers, testers, test automation engineers, Scrum Masters, agile coaches, SCM administrators, and the IT department. The result was unclear responsibilities, blaming, and committees (aka “steering groups”) who were forever discussing without anybody doing real work. The result? No progress. If this happens, do not try to hide the organizational problems with technical solutions and do not give up because “our product is too complex for CI. ”

Why not give up? Because every product group we have worked with who went through this “big rock removal” process toward CI has unequivocally found it immensely useful .

Recommended Readings

Original texts related to CI:

- Extreme Programming Explained , by Kent Beck. The term CI was first coined in the Extreme Programming method.

- Continuous Integration , by Martin Fowler. Probably the best CI description available.

Recommendations related to automating builds:

- Managing Projects with GNU Make , by Robert Mecklenburg. When working with C/C++, you will probably use Make. This book provides a great overview of Make and also talks about Make in large-scale development.

- Ant in Action , by Steve Loughran and Erik Hatcher. When working with Java, you will probably use Ant. This book’s focus is Ant, but it covers other topics. Maven –another popular build automation tool–is also covered.

- Groovy in Action , by Dierk Koenig, Andrew Glover, Paul King, Guillaume Laforge, Jon Skreet. Groovy is a recent JVM-based dynamic programming language. It has some excellent build automation support.

- Pragmatic Project Automation: How to Build, Deploy and Monitor Java Apps , by Mike Clark. A small book that covers lots of technology related to automating Java builds.

- Continuous Integration: Improving Software Quality and Reducing Risk , by Paul Duvall, Steve Matyas, and Andrew Glover. The focus of this book is on the automation of builds more than on the practice of CI.

CI in large development:

- “Scaling Continuous Integration ,” by Owen Rogers (also at: exortech.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2008/05/scaling-ci-3.pdf) in Extreme Programming and Agile Processes in Software Engineering 2004 Conference Proceedings.

Notes

- CruiseControl.NET is a CI system server for Microsoft .NET.

- For Java, ten minutes is too long. For C++, about average. For C, probably too short. Ten minutes is an average language-independent TDD cycle.

- To be more precise, avoid branches that live longer than ‘hours’. Branching has gotten easier with modern distributed version control systems such as Git and Mercurial. Some short use of short branches can be useful…but it is a sharp-knife tool that can easily be misused [Fowler09].

- Tip: Create a release branch off the mainline just before release, not at the start of a release (a release line).

- This was from a paper called Continuous Integration and Automated Builds at Enterprise Scale which used to be available at blog.aspiring-technology.com/file.axd?file=Continuous+Integration+at+Enterprise+Scale.pdf. Unfortunately, the link stopped working. If anyone has a new link to the document, let us know people.