Adaptiveness at product level can be reduced to three very concrete metrics:

The first key metric of adaptiveness is WIP at the product level (or train level in SAFe) at the end of the iteration. It does not matter how agile an individual team is if the product as a whole is overloaded with started but not finished work. This unfinished work at the product level directly takes away your ability to sharply change the direction of the product when the context or priorities change.

In a good LeSS implementation, the product lives in short cycles: 1–4-week Sprints, a single Product Backlog, a single Definition of Done (DoD), and a single shared Increment for all teams. This creates the possibility of having WIP ≈ 0 at the end of every Sprint at product level: everything that was started is brought to Done, and the next iteration starts with a clean system.

In SAFe, work is aggregated around the Agile Release Train and Program Increments (PIs), usually 8–12 weeks. At PI Planning the train takes on a significant amount of work in advance, teams fix their PI Objectives and commitments, and the real “reset” of product/train WIP happens only at the end of the PI, while inside the quarter the train lives with high systemic WIP.

The more often product-level WIP returns to zero, the easier it is to radically change priorities without breaking the entire plan. LeSS is deliberately aimed at enabling the product to reconsider the entire Product Backlog every Sprint, while SAFe is aimed at enabling the train to hold its commitments over the PI horizon.

The second metric is Lead Time from idea to potential value. Lead Time makes sense to measure at the product level: from the moment a new idea or request first appears in the Product Backlog to the moment when the change is part of a Done Increment and carries potential value for the user.

In LeSS, short Sprints and a single Product Backlog make it possible to quickly “push through” high-priority items across the entire product: the Product Owner reorders the Product Backlog, and already in the next Sprint several teams can focus on a new idea, turning it into potential value ready for release.

In SAFe, major course changes are more often reserved for the PI boundary: changing a significant part of the PI Objectives in the middle of a PI is expensive, politically difficult, and risky for train synchronisation. Formally, Increments can be released more often, but the organisational design of the train nudges you to wait for the next PI Planning for serious changes, thereby extending the actual Lead Time from idea to potential value for unexpected requests.

The third metric is a proxy for “switching costs” at the product level: the percentage of items in the Product Backlog that can be worked on by at least 80% of the product’s teams.

In LeSS, the structure is deliberately rebuilt around feature teams: they are cross-functional and cross-component, capable of delivering end-to-end product features without dependencies. Regular multi-team Product Backlog Refinement sessions create shared understanding of product items across several teams, and the share of items that, in principle, can be taken by the vast majority of product teams grows over time.

In SAFe, train teams often specialise in components, subsystems, or narrow domains. This reduces the percentage of items in the product/train backlog that are available to most teams and increases the dependence on specific teams as “bottlenecks” for particular areas.

From the perspective of Transaction Cost Economics (TCE), this is a direct impact on transaction costs and switching costs: the higher the percentage of items available to ≥80% of product teams, the cheaper and faster the product can reassign work in line with changing priorities, and the less it gets stuck in an outdated plan.

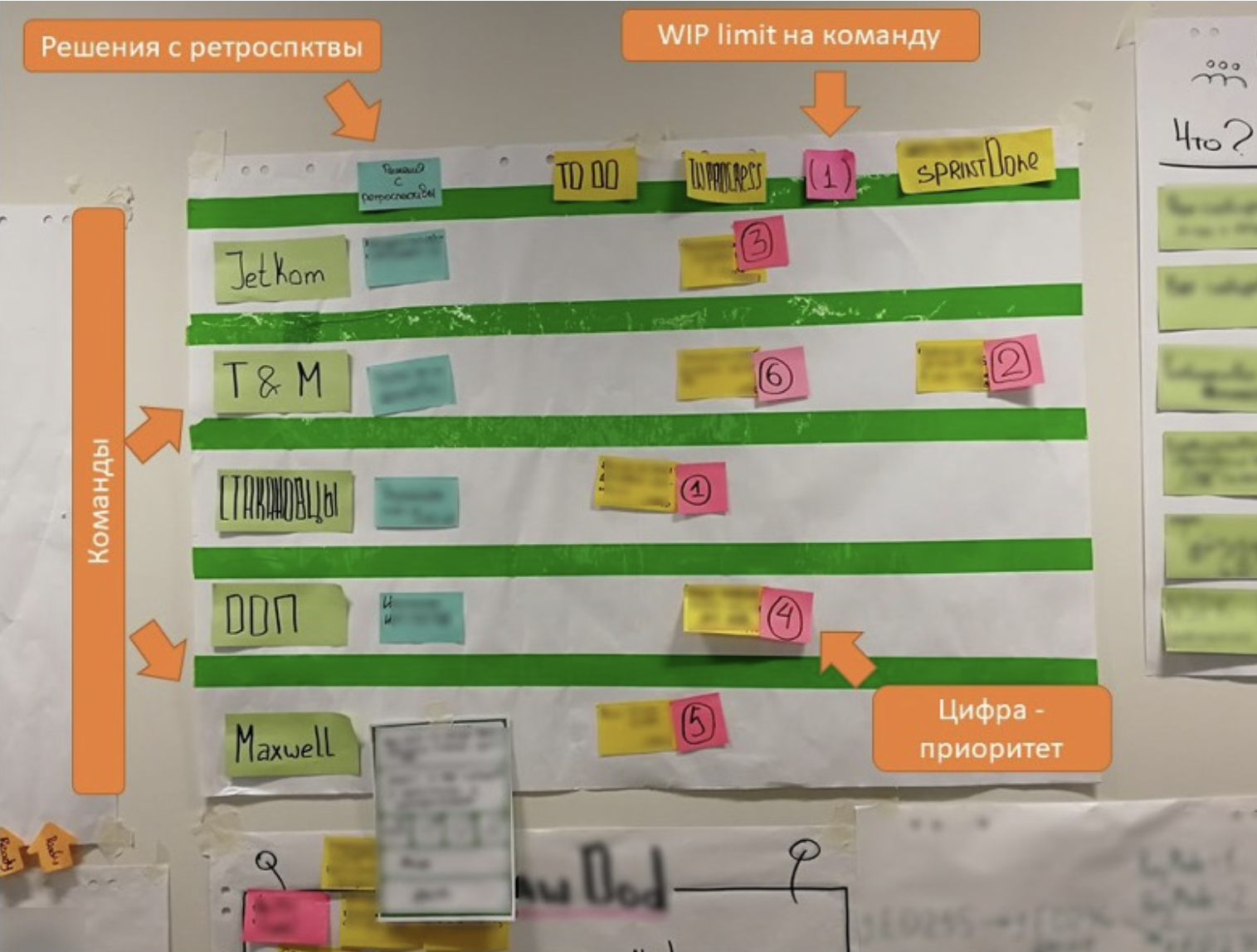

In one of the LeSS cases (SBP), it is clearly visible how these three metrics show up in practice exactly at the product level.

There were five interchangeable feature teams working on a single product in two-week Sprints. Each team could take almost any product feature within the domain — thanks to the feature-team structure and regular multi-team PBR, where teams jointly refined items from the shared Product Backlog. This gave a high percentage of items available to most product teams, and not just to one or two “elite” teams.

In the photo of the board from the middle of the Sprint there are three columns (roughly: To Do / In Progress / Done) and WIP = 5 at the product level: each team has one feature in progress, and all items are moving towards Done. At the same time, by the end of each two-week Sprint, product WIP systematically tended towards zero: everything started was brought to Done, and any unfinished work was consciously removed and returned to the reordered Product Backlog, opening the way to new priorities and new potential value.

As a result, the product in this LeSS case had high business flexibility:

LeSS optimises adaptiveness at the product level through a single Product Backlog, a single Increment, feature teams, and multi-team PBR, which together create the conditions for frequent “resetting” of product WIP, reducing Lead Time and lowering switching costs thanks to high team interchangeability.

SAFe optimises coordination around the train and the PI: this gives a strong synchronisation structure, but often at the cost of higher product WIP for the whole quarter, a long path from idea to potential value for unexpected changes, and strong dependence on specialisation of train teams, which increases switching costs.

What to choose? Ultimately, it all comes down to an honest answer to the question: what level of flexibility do you really need?

If you operate in a low-competition market — for example, you are a state monopoly or a large organisation with slowly changing regulation and predictable demand — then SAFe might indeed be enough for you, where you can reconsider the product direction every 8–12 weeks at the PI level.

If, however, you live in a turbulent market — fintech, e-commerce, online services, B2C products with strong competition — and want to be truly flexible, to change product direction every 1–4 weeks, then you need to keep WIP and switching costs low at the product level, and your choice is LeSS.