Solarwinds

Incremental LeSS Adoption at SolarWinds

Disclaimer: This text describes the situation in one of the SolarWinds product groups until 2017, i.e. roughly three years before the event known as the Sunburst supply chain attack that happened in late 2020. Any statements in the text are unrelated to the attack.

Background

SolarWinds is a leading provider of IT management software, its products are used by tens of thousands of IT professionals around the world and allow them to have a better overview of their networks, applications, databases and other elements of the company IT infrastructure. One of its first products, Network Performance Monitor has been in development since 2001.

Soon after, the second product with a similar focus followed. Both products together created a family of products called the Orion family. The company realized that both products have many things in common and created a common platform - Core - the subject of this case study. Core has been developed by a group of 5-6 teams.

The company was successful and over time added the third, fourth, and even tenth product.

This caused the platform to expand the number of use cases to cover. In addition to serving more modules from a technical point of view, the Core teams (which are component teams) needed to coordinate work with more and more module groups (consisting of other component teams). As always with component teams, that led to a complicated planning and estimating process that took months, and of course was significantly invalidated after the planning, due to the realities of change and imperfect insight. The company hired many managers and fake “Product Owners” (actually, project managers and business analysts) to deal with the coordination problems, and with each additional manager prioritization was even more fuzzy because each had their own agenda and priority list. These management “quick fixes” always “fixed” the situation only temporarily because their long-term effect was increasing the organizational complexity.

The management was frustrated. There were so many capabilities they wanted to add to Core (new UI look and feel, support for high availability, make customer upgrade experience seamless). But the Core group was so occupied by the module requests and maintaining the current features that it had no capacity to add new capabilities to the product. Management came with the following approach: separate greenfield initiatives each focused on developing a new capability for all modules (e.g. a new UI framework, a new installer) - another instance of a quick fix. Predictably, that further increased the integration complexity and time to deliver the whole product build to customers.

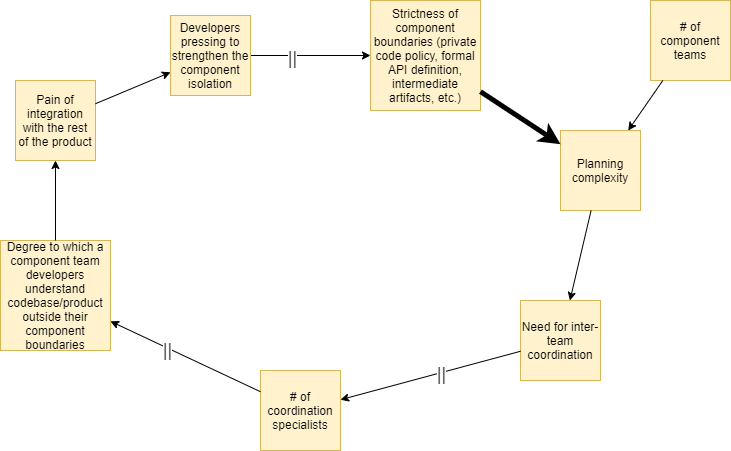

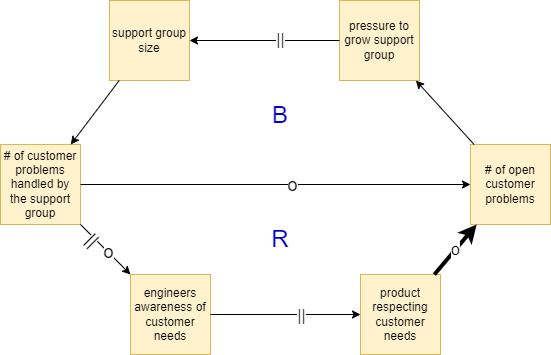

These quick fixes failed because they didn’t address the root cause - the existence of the Core teams (component teams), since the number of component teams increases planning complexity, dependencies, delay of delivering end-to-end customer features, and the need for coordination. The need for coordination is often handled by adding more coordinators (a management quick fix) which further decreases the ability of the teams to understand the whole product and creates a pressure for more strict component boundaries which again increases planning complexity. Of course,the whole vicious cycle can be eliminated or avoided if component teams are removed, or not introduced in the first place. Figure 1 illustrates the dynamics in a system model.

However, Core was introduced as a dedicated component group. Then, predictably, the following dynamic started (referring to 11 laws of systems thinking here). Adding a new coordinator was a “quick fix” that temporarily reduced coordination complexity. However as a result, organizational complexity grew, so after a while the need for coordination was even higher than before. (Law 3: Behavior grows better before it grows worse.) The delay between these two events made it more difficult to see. (Law 7: Cause and effect are not closely related in time and space.)

Having more coordinators (and thus higher organizational complexity) was a result of a long-term adhoc response to problems. It has its roots in the past, when the first coordinator was added, and then the next and then next and next. (Law 1: Today’s problems come from yesterday’s solutions). Each of these steps was seemingly innocent and harmless and seemed to make sense at the time - add one more coordinator. (Law 4: The easy way out usually leads back in.) With each additional coordinator, teams and senior management became more addicted to the results of the coordinators work (usually some intermediate artifacts such as a project plan, status report, acceptance criteria written down for each “story”). Soon nobody could imagine organizing work without them. (Law 5: The cure can be worse than a disease.)

Scope of the Adoption

The root cause of the coordination problems and more coordinators was the very existence of component teams, and so the solution is their elimination. But it wasn’t possible to make this structural change because of the false (and false dichotomy) management belief that work organized to (large) component teams is the only way of developing large products..

Given the constraint that we couldn’t eliminate the Core group, to at least achieve some minor improvement in increasing adaptiveness and more likely working on valuable items, we decided to change the following organizational design elements for some minor incremental improvements

- Define the “Product” as broad as possible

- Reduce the number of explicit and implicit backlogs in the organization

- Reduce number of coordinators

This case study shows how we used these elements to make the first incremental step towards the system optimizing goal of increased adaptiveness to more easily learn and pivot to working on newly-discovered more-valuable items.

Because we didn’t eliminate the first-order influencing factor - the existence of component teams - it led to a slow and painful partial LeSS adoption and the improvement towards the system optimizing goal was limited.

For example, the decision to use Core as an initial “Product” didn’t allow us to prepare a potentially-shippable Product more often, which delayed feedback from customers.

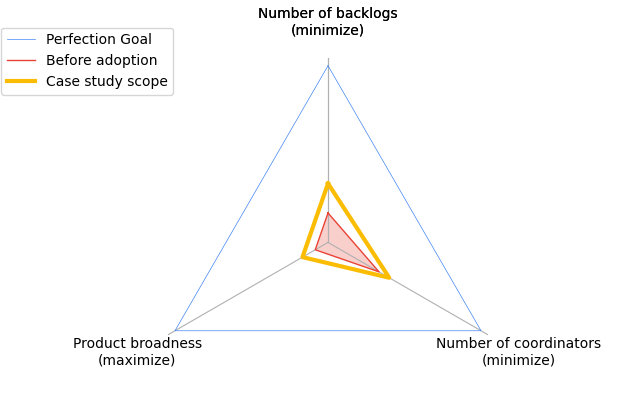

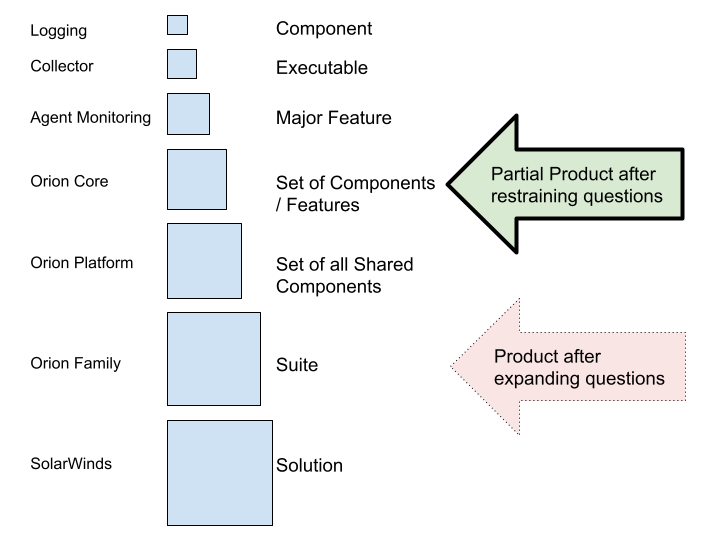

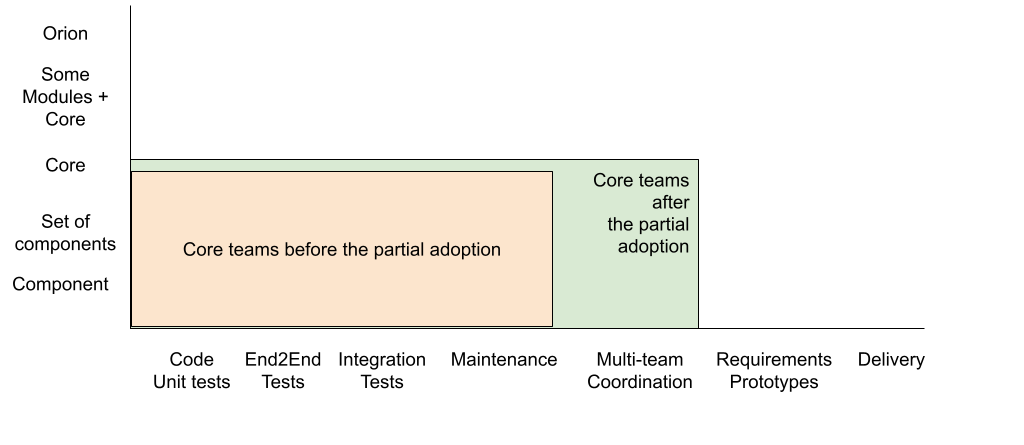

The perceived progress made in the first step is shown in Figure 2.

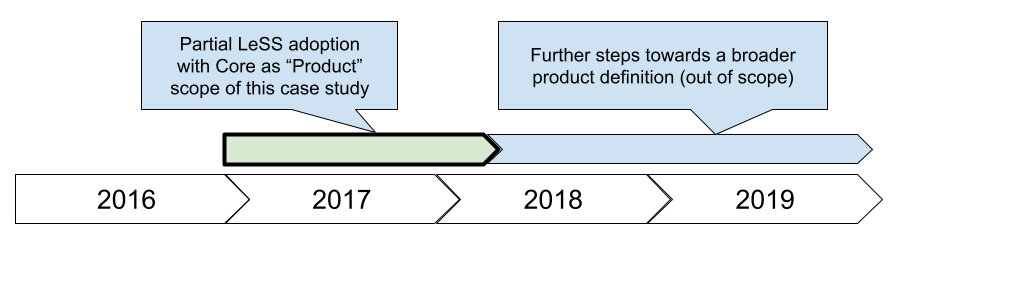

The partial adoption continued later with further steps that are out of scope of this case study. These steps included further broadening of the product definition and reducing the number of backlogs. See Figure 3.

But first things first. Let’s describe how the product development group had been organized before the adoption.

Initial state

Architectural Background: The Orion family consisted of multiple “modules” (i.e. components), e.g. NPM (Network Performance Monitor), SAM (Server & Application Monitor) and VMAN (Virtualization Manager). Each module focuses on monitoring a different aspect of the customer company infrastructure. For example, NPM monitors traffic on key network interfaces, VMAN monitors e.g. virtual machines, disks. A module can be downloaded and installed separately but all modules can also be installed together on the same server (as a product suite).

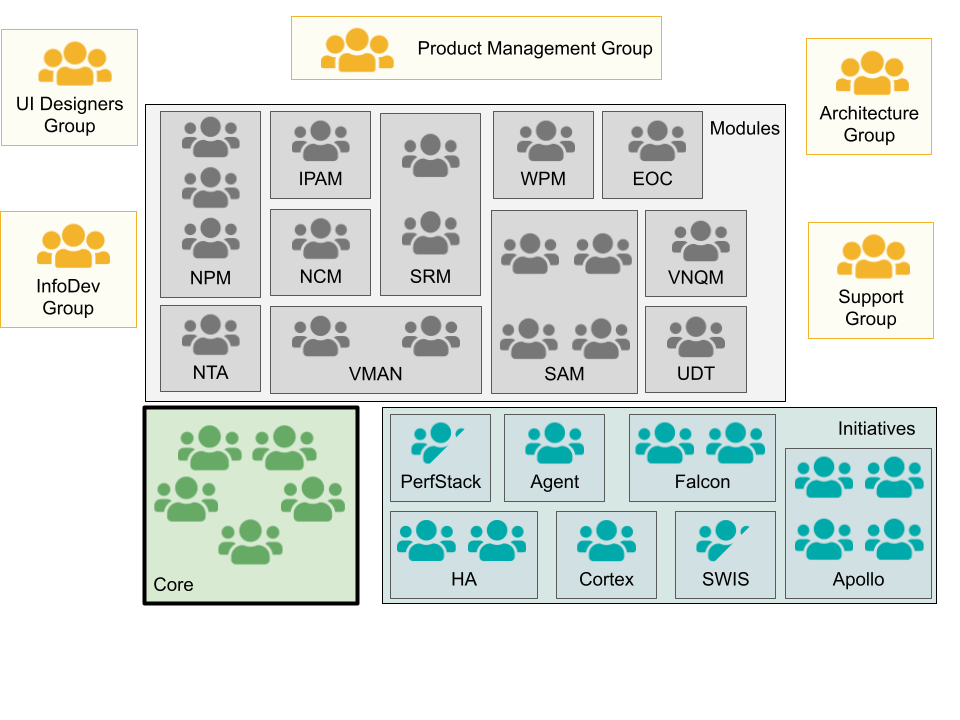

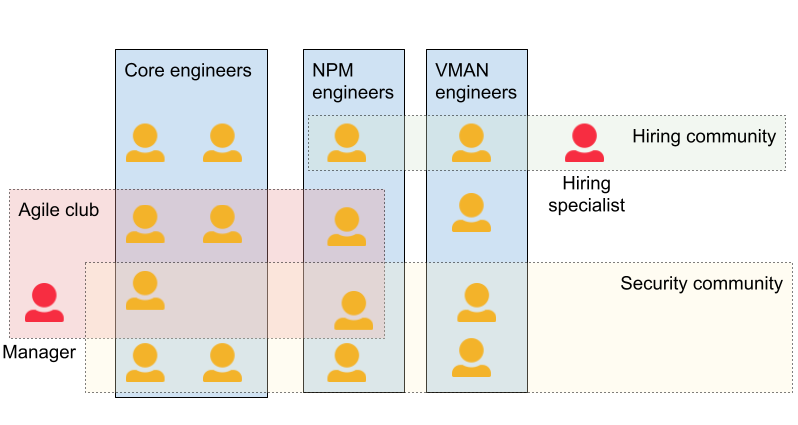

Before the LeSS adoption the development organization was structured in the typical local optimization of component teams, in the following way (see Figure 4):

- Module teams - each module group (e.g. NPM, SAM, VMAN) typically had its own development group consisting of one to three teams

- Core group - responsible for maintaining the majority of the shared components (e.g. user management, DB access layer) and some user-centric features (e.g. node and volume monitoring) consisting of 5 (later 6) teams.

- Partial LeSS adoption in this group is the scope of this case study.

- Initiative teams - as the need for shared services or components was growing and the Core team was unable to deal with the need to deliver new features, separate greenfield initiatives were set up by management. Like the Core group, each focused on developing a new capability for all modules (e.g. a new UI framework, a new installer)

- Other groups - some roles like architects or UI designers were not members of the engineering teams but created separate functional groups.

Approach to adoption

Initial Product Definition

To maximize adaptiveness it would be ideal to use a product definition that is as broad and end/user/customer-centric as practical (Book 3). “Define Your Product Guide” from Book 3 recommends defining the Product using expanding and restraining questions. Let’s revisit how they had been applied in our case.

Expanding questions

What would the end customers answer if we ask them, “What is our Product?”.

The answer to this question would probably be “SolarWinds”. Taking into account that Orion customers probably don’t know the complete SolarWinds portfolio and think SolarWinds=Orion we can safely modify this answer to “SolarWinds Orion Suite”

Do we have components that are shared or functionality that is the same across our current Products?

Yes, actually the majority of the code for Orion family was shared. It also shared the same UI patterns like dashboards, charts, menus, etc.

Our Product is part of? What problem does the Product solve for end-customers?

The users (who are almost equal to customers according to the SolarWinds business model) need to monitor their company infrastructure and be informed about any important events happening there.

Restraining questions

What is the Product vision? Who are the customers? What is the Product’s customer domain?

Different Orion modules serve different customers - e.g. network engineers vs system engineers. However, there are commonalities between the Products and the company actively tries to cross-sell multiple modules to customers who had already bought one module. So the answer to this question would advise us not to restrain the product definition.

What development is within our company? How much structural change is practical?

The last question was the most difficult. The guide includes considering department boundaries as a possible way to restrain initial product definition, especially if there are dysfunctional management-political forces that make it difficult to go broader. Further guides then recommend expanding product definition later. That makes the initial change politically easier as the amount of structural change for LeSS adoption is minimized.

On the other hand, there is a risk that the departments represent component teams and therefore an initially defined “Product” will cover only a set of components and not be a true end-to-end customer-focused Product. Also, without a structural change it is easy to miss how deep (front-to-back) LeSS adoptions are supposed to be, as the other supporting roles or intermediate artifacts will most likely remain intact, because they need to serve the departments not participating in the LeSS adoption and will likely interfere with the adopting group. Therefore, while the initial adoption may be easier, the forces in the rest of the organization may be strong enough to revert the initial change later.

Another weakness of starting with a partial product definition that is only a set of components (rather than a true front-to-back definition) relates to manager status quo political games: The managers of the existing component teams will want to keep the existing structures so that their positions are not threatened. By allowing a “Product” definition to start with just a set of components opens the door to distorting the change intention so that components can be incorrectly called a “Product” and then component managers can be (fake) “Product Owners.” This has been observed many times in the myriad fake “scaling agile” adoptions around the world.

An alternative way of thinking would be to ignore this question and keep the initial product definition unrestrained. That would typically mean that we are in a LeSS Huge situation, which makes the adoption more complex - we would need to include multiple groups into the initial discussions, adoption would take more time (with one Requirement Area at a time) and would therefore be more vulnerable by company politics.

Choosing the Product

As you can see, it is not an easy choice. In our case, if we take the output of the expanding questions (SolarWinds Orion Suite) as input to this step we end up with the Product consisting of hundreds of thousands of lines of code in C#, C++, Javascript, SQL, python, go, VB6. The total number of teams developing the Product is 30-40 even if we do not count additional roles currently not included in the teams (architects, UI designers). Even if we imagine removing all coordination roles and imagine reduction of required developers for a simplified Product, it will still mean that we need more (probably a way more) than recommended 8 teams for a smaller LeSS adoption. This means that we are in a LeSS Huge situation.

Out of the two options described above we had chosen the first one: restrain the initial product definition to one department - “Core” (a multi-component group highlighted in Figure 4). Why? Doing structural change for multiple departments in multiple locations seemed … scary. We assumed that our initial “Product” will later become a Requirements Area for a larger Product, so we tried to keep other properties compatible with a typical Requirements Area definition, namely:

- Appropriate size - five teams at the time of adoption, later expanded to six teams

- Partial customer orientation - although “Core” served as a shared collection of components and services for other parts of the Orion suite, the Core teams had been able to deliver some customer-oriented features themselves (for example, monitoring and visualizing CPU utilization of a network element)

To reduce confusion, we will further use the term “partial Product”, “partial-Product Backlog”, etc. when referring to Core and the term “Product” only when referring to the Product after expanding questions (the Orion suite).

We believed that this partial Product would serve as a role model for the other departments later - delivering customer-oriented features with a decreased need for coordination by managers. However, later we realized that it was not a good first choice. In particular the fact that Core was primarily a multi-component group and served internal stakeholders instead of customers led to typical problems:

- Partial-Product Backlog was full of technically-oriented component tasks instead of end-to-end customer features (see section Product Backlog)

- Major coordination effort was still required to integrate Core work with module and initiative work to deliver customer-oriented features. A customer-oriented feature often needed implementation in both module and Core codebase. Due to the fact that both groups had different partial-Product Backlogs, this work had to be planned, tracked and checked at the end.

- One month long test phase before each release was another example of coordination effort required between modules and Core.

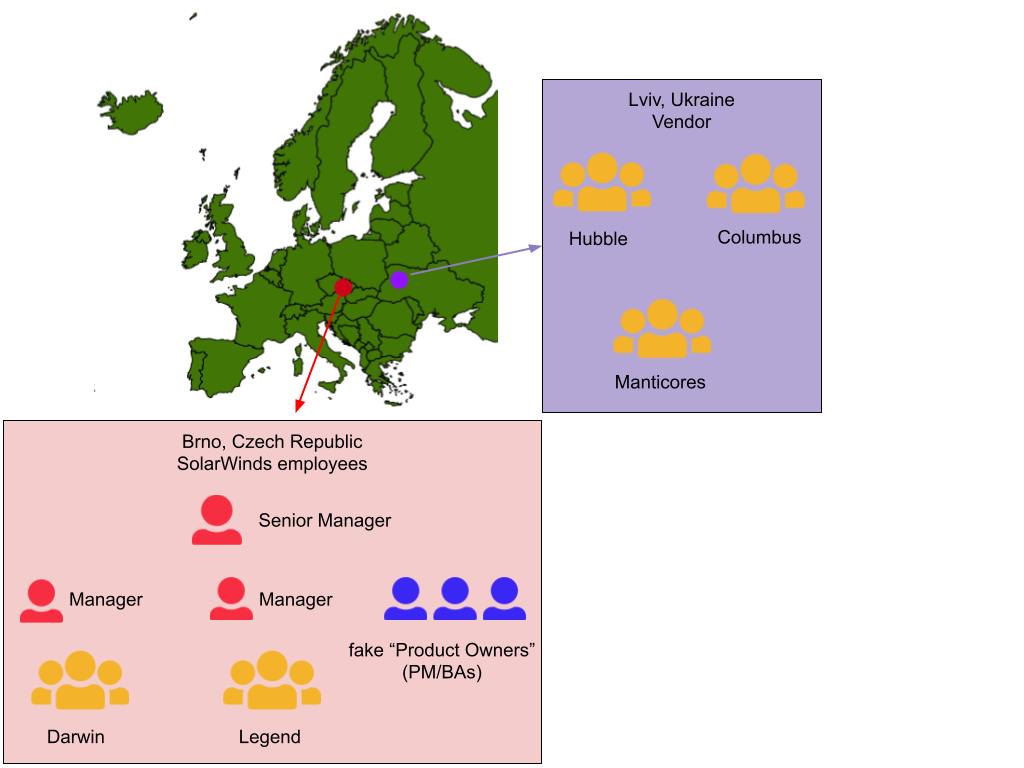

For completeness, there was one more reason considered but dropped against choosing “Core” as the initial scope of the product definition, which we were aware of from the beginning: the fact that the Core teams had been located in two sites (Brno, Czech Republic and Lviv, Ukraine). We had at least a little concern that including two sites of teams in the first step of the change would be too risky. Moreover, the Lviv teams had been employees of a vendor, not SolarWinds itself. However, this disadvantage was perceived as relatively small. Nevertheless, we were careful to overcome communication boundaries that naturally arose and including the two sites didn’t turn out to be a major obstacle.

With Core as an initial Product (see Figure 5) we can show progress of the partial adoption on a feature team adoption map on Figure 6.

Steering part of the organization towards more adaptiveness

Defining the initial “Product” as Core (essentially, a big component) constrained further changes we could make. This section will describe how we reduced the number of coordinators, reduced the number of backlogs, and it also outlines some effects of a slightly broader product definition on team coordination.

Before we do this, let’s recall some aspects that were common to all these activities - my personal role in the engineering group and education of people before adoption.

History

In 2015, about a year before this case study, I was a member of a group that introduced “Scrum” to the company, which in retrospect mostly meant introducing Scrum theater in the company, with one notable exception. We established the concept of a Team: 5-9 members, long-term membership, partly cross-functional (programmers and testers), but not cross-component across all the components of Core. In 2016, I accepted a position of one of the many inter-team and inter-group coordinators. My official title was “Product Owner”, but as usual in most “agile” faux adoptions, it was just a synonym for a project manager. My assignment was Core. With five teams working in one group I was looking for better ways of organizing the work, for example prioritizing the backlog based on global priorities or looking for ways to gather feedback from customers more often. Starting with LeSS seemed like a natural choice.

Education

I gave the third LeSS book to two first-level line managers and a potential partial-Product Owner and asked them to read chapter 2 (Introduction of LeSS). Scrum Masters had discussed LeSS a couple of times in their community. I had the most LeSS knowledge - reading all three LeSS books and working as a Scrum Master in a large-scale context for 12 years. And that was it.

In retrospect, the education was desperately insufficient. LeSS adoptions are complex and need deep understanding of all involved participants - management (both first-level and higher management), engineers, Scrum Masters, business departments. All these people need to thoroughly understand the effects of the organizational structure elements on teams and the whole organization before the adoption starts. It is a warning to all people eager to start LeSS adoptions not to start them too early - not before they understand the organizational design and dynamics of their organization.

Reducing the number of coordinators

Core organizational structure before adoption

Core engineering group was organized into teams (see Figure 7). Teams were typically long-term, the same people stayed together for months or even years until natural attrition or the need for fresh air into the team. Each team had a name of their own choice, for example, Hubble, Legend, Darwin. The team size was usually 5-9 members with the bias towards the lower end of the scale. The teams consisted of developers (mostly C#, rarely other languages) and testers. The teams were always collocated. (Guide “Team Based Organization”, Book 3) Typically, members of a team reported to the same engineering manager and a single manager managed two teams. Scrum Masters existed as well and they had been part-time team members.

Other roles outside of the teams still existed, for example, UI designers, documentation writers and architects. These employees fell under different management structures and they were often located in different countries like the US. Of course, it reduced adaptiveness because teams could only deliver features preprocessed or post-processed by these other specialists and could not easily change course. This aspect is visible on FTAM on Figure 6. Also, the existence of these roles generated some amount of coordination work, which has been mostly handled by dedicated coordinators.

In contrast, if we use real Scrum teams we include all these roles in the teams and as a consequence coordination work would mostly happen inside self-managing teams without the need for external coordinators.

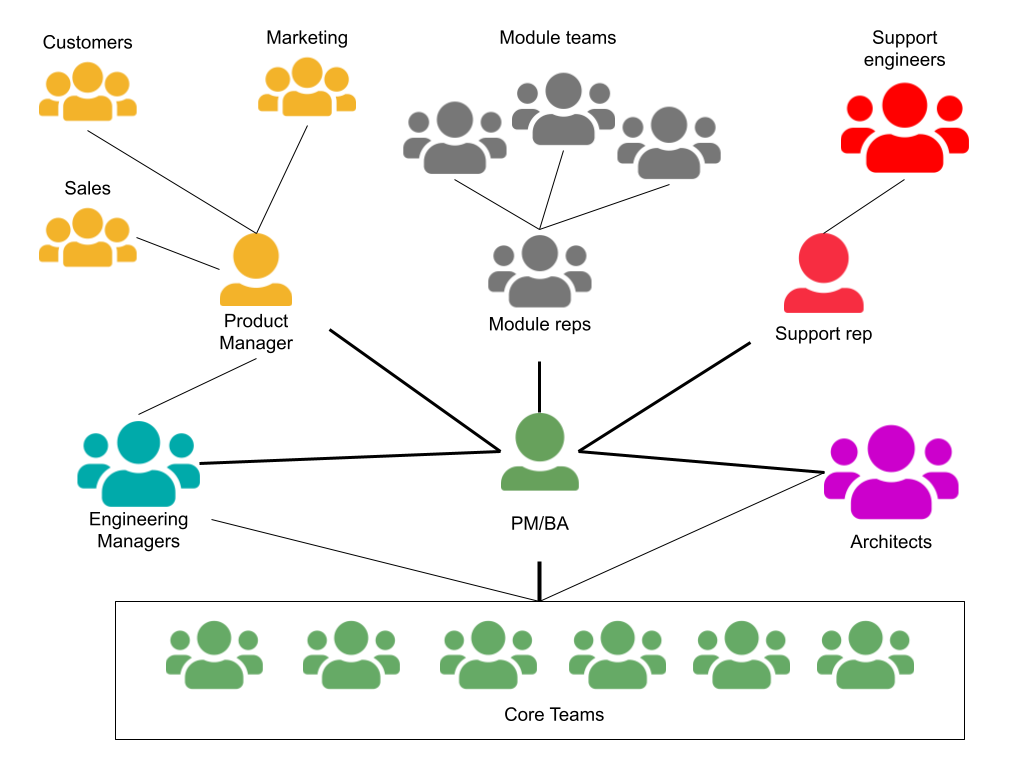

Engineering managers and the fake “Product Owners” (in fact project managers and business analysts = PM/BA) reported to one senior manager who bore ultimate responsibility for Core.

The teams were placed in two locations: two teams in Brno, Czech Republic, three teams in Lviv, Ukraine. The three Ukrainian teams were not employees of SolarWinds, but hired by a vendor company and working for SolarWinds based on contract. However, all of the above is valid also for vendor employees - they were organized in long-term teams consisting of developers and testers. No other product development roles were present on the vendor side. The most experienced vendor employees worked for SolarWinds for close to 10 years.

The vendor teams didn’t formally report to SolarWinds management but to local vendor management. The vendor organization appointed a contact person that served as a counterpart of the senior manager for people-related decisions like hiring or firing developers. Other than that the contact person had no authority over the work of the teams.

Fake “Product Owner” (PM/BA)

Work items for teams had been prepared by fake “Product Owners” who were not that, but just people doing project management and business analysis activities (PM/BA). They were also responsible for coordinating team work with other teams in different groups (e.g. modules) and with other roles (e.g. UI designers), see Figure 8.

As a consequence, PM/BAs had so much on their plate that they could rarely manage more than two teams. When more than two teams were needed a new organizational unit was created with another PM/BA. Core had five teams with three PM/BAs.

For Core, coarse-grained backlog prioritization was done by one Product Manager who was responsible for communication with customers and other parts of the business like top management, sales or marketing. He should have been the one and only one person playing the role of (partial Product) Product Owner.

Reducing the Number of Coordinators

Figure 7 shows that there were three PM/BAs assigned to Core. We decided to reduce this number to one to reduce the number of coordinators and to create pressure for teams to start coordinating their own work. So the next step was convincing three individuals skilled at business analysis and project management to find a new role - a usual problem even for partial LeSS adoption which is explored in the Guide “Job Safety, but not Role Safety”.

Fortunately for the adoption (though not so much for the company), two of them decided to leave the company before the partial adoption started (for unrelated reasons) and the third one (myself) wanted to be a Scrum Master. So a new person for the role was found. He transitioned from a different part of the company and also changed his role from a test lead. Having a new person in the role emphasized the fact that the adoption of a new approach starts.

To improve adaptiveness it would have been even better if the role would have been filled by the existing product manager, a classic Scrum choice for someone approaching a real Product Owner, but organizational constraints prevented us from doing that. He was simply from a different department and engineering management was convinced that they needed someone from the engineering department to be responsible for coordination with the other groups in the company.

One of the key tasks of the PM/BAs was to maintain a balance between requests from different groups of stakeholders (see Figure 8), which consumed a significant part of their working time. By having only one PM/BA it became clear that he could not do this work at the previous level of intensity - some had to be done by the teams themselves. The techniques we used for it were Product Backlog Refinement and common Sprint Planning.

Product Backlog Refinement

With one PM/BA per one or two teams, teams were used to a much higher level of detail being given to them in the form of product backlog items, usually in a written form using acceptance criteria. This changed with only one PM/BA. Being alone he had no capacity to analyze requirements coming from stakeholders in detail because he had much more on his plate. He had to spend some portion of his time prioritizing or reporting to management. He also had to manage undone work, tasks existing because of the teams’ insufficient Definition of Done. The teams were encouraged to talk to stakeholders to clarify details of their backlog items. Stakeholders were willing to discuss with engineers, but as they were typically located in different offices (even different time zones) and spoke a different language, clarification constituted a challenge especially for some of our introverted developers. The teams often delegated the clarification to the most eloquent team member, which again created an information bottleneck, delay, information scatter and loss, and more misunderstandings and “requirement defects”

Also teams were not talking directly to users/customers, but just to internal stakeholders within the company. Even some of these internal groups didn’t talk directly to customers! As a result each group of internal stakeholders came with different ideas of how to implement backlog items and which items to implement first. That generated conflict and a lot of discussions - another consequence of choosing Core as an initial Product.

In other words, by introducing one PM/BA we reduced the number of coordinators and passed some coordinating and clarifying work to the teams (which supports team adaptiveness), but we didn’t significantly reduce the total amount of coordination work.

Try … diverge-merge for backlog refinement

It was interesting to experiment with different formats of the Product Backlog Refinement in a multisite scenario (each team collocated, but teams in multiple sites). Since the beginning we struggled with less interactivity and engagement compared to local sessions. The real, deep discussions happened locally just after the official refinement session had finished. It almost looked like people were waiting for an official end of the meeting so that they could start talking! We tried various experiments to make the sessions more interactive, e.g.

- invite external experts to bring more insight,

- have an advocate for each backlog item who studied it before the session,

- use a shared document to work with during the session.

None of them really helped the participants to overcome language, physical and psychological barriers caused by the multi-site setup.

Finally, we iterated towards the following model that uses diverge-merge cycles (loosely inspired by Guide “Multi-Team PBR”, Book 3). We started with an Overall PBR using a wiki page where the PM/BA copied a list of items he wanted to be refined. The teams marked each item for local refinement in Brno or Lviv. Then two local Multi-Team PBRs were organized in parallel where teams refined selected items without site or language barrier. These local sessions were usually attended by all team members.

A couple of days later an Overall PBR session was organized. Team reps from one location introduced the results of the local refinements to the team reps from the other location.

Sometimes we intentionally let both locations refine the same items in parallel to potentially discover two solutions. This way everybody had a chance to participate in the deep local session as well as keep an overview of the complete backlog.

This model is not ideal and the teams continue to experiment, but we deemed it as good enough at that time.

Sprint planning

Before the LeSS adoption teams had team backlogs.The teams were used to preselect some items from their backlogs and move it to their virtual Sprint space before the Sprint Planning. Also the unfinished items from the previous Sprint were almost automatically added to the currently-planned Sprint.

The first LeSS Sprint Planning One meeting was different. Not only there was only one (partial) backlog, but also no preselection was used and unfinished items were all returned back to the backlog and teams were told that we were starting from scratch (Guide “Sprint Planning One”, Book 3 - a group of teams with a set of items). In short, all decisions were expected to be made directly on the Sprint Planning One meeting. Teams were surprised but accepted the fact and we began the event. It turned out that some previously preselected and leftover items were no longer the most important and different items were selected for the Sprint. This first planning event was long but a new standard was established.

Still the Sprint Planning One event suffered from two problems:

- Sprint planning with 5 (later 6) teams was long and most of the time people passively sit on the call and wait for their turn

- The current tooling was not good enough in visualizing the team’s speculated load for the Sprint.

The following sections describe an experiment that tries to overcome these difficulties.

Try … multisite Sprint Planning in a shared document

The PM/BA chose enough items for one Sprint in a private document by copy-pasting them from the tracking system. The facilitator of the Sprint Planning event prepared the following document with all team reps and the PM/BA having edit access to the document.

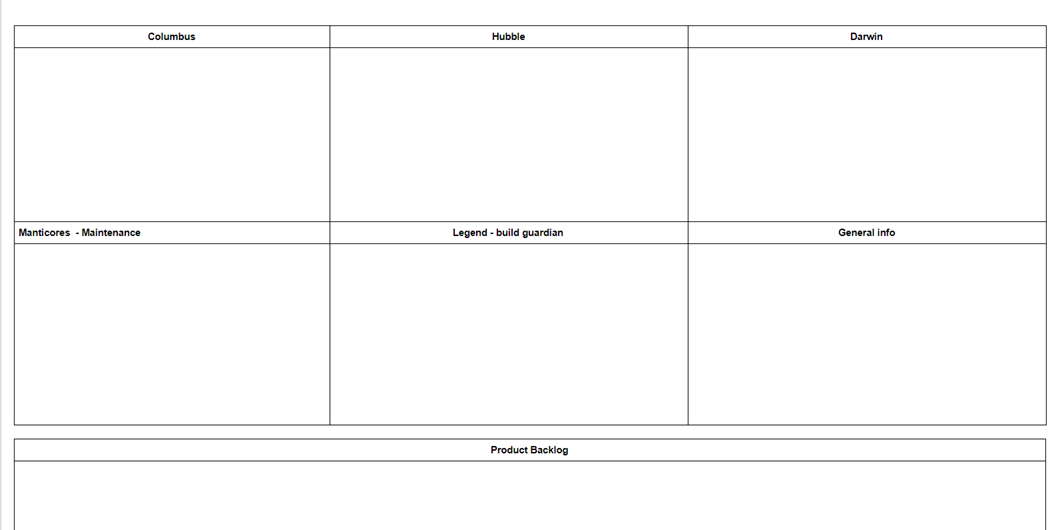

The first five cells constitute space for team Sprint plans. Each cell was identified by a team name (e.g. Columbus, Hubble, Darwin) The sixth cell can contain a general Sprint info (e.g. Sprint goals, public holidays)

The PM/BA started Sprint Planning One by communicating the goals of the Sprint and providing general info. After answering all questions he started copying backlog items to the “Product Backlog” area below the team cells.

Whenever he copied a batch of items to the document, team reps started moving the items to their cells all at the same time in parallel. This limits waiting and increases engagement of the team reps in Sprint Planning. When all items from the first batch were distributed, the PM/BA copied the next batch and so on until all teams were full.

At each moment it was highly visible how many items each team forecasted for the Sprint and their decisions can be challenged by other teams, if any conflict arose it was solved on the spot. For example, when two teams wanted to work on the same item, their reps immediately agreed which team is more suitable for the item, for example if they wanted to learn more.

Usually the team with the best knowledge took the item, but sometimes a team asked for an item from a new area and if they really wanted it the team with a better knowledge “allowed” them to take it. When no agreement could be reached (a very rare case) we had to roll a (virtual) dice to distribute an item which nobody wanted.

After Sprint Planning One was finished the agreed plan was reflected in the tracking system. The PM/BA then informed the rest of the world about the results of the Sprint Planning One. The whole meeting usually didn’t take more than 30 minutes with five teams. It reduced waiting and greatly improved transparency and coordination

Number of backlogs reduction

Product Backlog

Our starting point was having multiple explicit and multiple implicit lists.

Each of the PM/BAs had their own explicit list for a few teams.

And there were many more implicit lists too. That is, if Team X was the specialist for task Y, then Team X did Y, a local optimization which degraded the adaptiveness (agility) of the teams to do new and different work, due to their narrow limited knowledge. In this way, even though there was only one explicit list for multiple teams maintained by each PM/BA, in reality there were N implicit lists for the N teams, each for their single specialization.

With the elimination of the multiple PM/BAs (and their multiple explicit lists) and moving to only one PM/BA for all the teams (the “partial-Product Owner”) these multiple explicit lists disappeared and only one explicit prioritized list was maintained.

Though having one explicit list enables more adaptiveness than multiple lists it still suffered from deficiencies preventing improving adaptiveness significantly:

- Most items were not end-2-end customer-oriented features, but just component tasks

- Only coarse-grained items might possibly benefit stakeholders and prioritization typically happened on this coarse-grained level

Let’s look at these two issues in detail.

Lack of customer orientation in product backlog items

The content of the backlog was constrained by two important factors:

- initial product definition

- teams setup

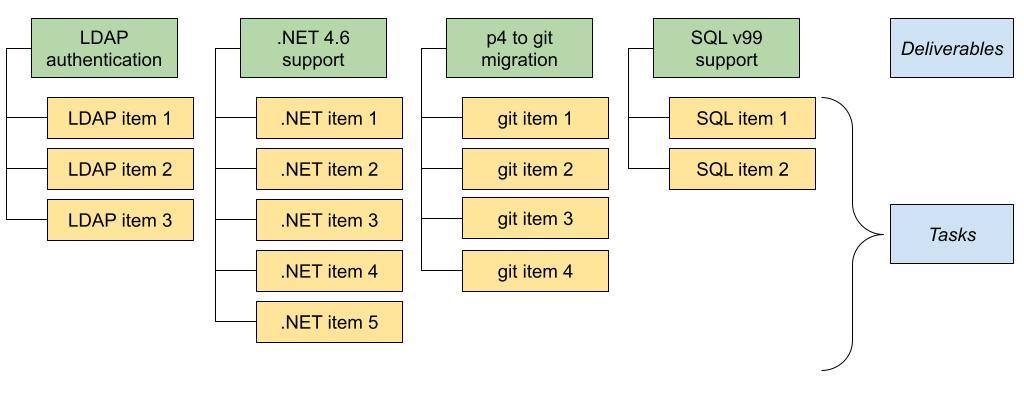

Both of these factors left some groups outside Core teams intact. Having Core as an initial partial Product meant that module teams existed outside of the initial Product group. Having only developers and testers in the teams meant that architects, UI designers and support reps existed outside of the initial Product teams. All these groups had their own interests and some of these manifested as items in the Core backlog. Some examples:

Architectural improvements - Architects (a separate group, see Figure 4) came up with ideas for new architectural elements that were hypothesized to bring benefit later.

Module requests - Some requests started as a customer request to a module team. The module team then did a preliminary analysis and realized that the request has a “module part” and a “Core part”. The Core part was put to the Core list often without the original business context.

Engineering improvements - these were brought by engineers themselves and reflected the inability of programmers to improve the Product incrementally.

Customer features - a Product manager did the job of market research and brought a couple of coarse grained items to the Core list.

Supportability improvements - Usually brought by support representatives and engineers who worked with real existing customers. They were supposed to address the pain experienced by the current customers.

Coarse-grained prioritization

Two factors influenced the fact that coarse-grained items were the perceived unit of prioritization:

- six-month release cycle driven by The Contract Game

- backlog items were defined by internal stakeholders

We discuss the long release cycle in later sections, now we would like to focus on its effect on backlog items. When stakeholders have a one-in-six-month chance to get something into the Product they want it to matter. They see this vast six-month space in front of them and imagine all the big things that can be delivered in this time period. As a result, the items they initially propose are typically bigger than necessary with all the bells and whistles they imagined.

The second effect that plays a role here is the fact that the backlog items are not defined by customers themselves but by internal stakeholders - typically company middle managers. The stakeholders spend different amounts of time with real paying customers - some of them close to zero. When they lack direct contact they speculate. When speculating they want to cover all bases (because what if they are wrong) and therefore their proposed backlog items tend to be more complex and bigger than necessary. This effect is stronger with the distance of a stakeholder from the real paying customer/user.

This thinking is based on the assumption that company top/middle managers know in advance what is best for the customers. This is rarely true. Even if all managers are domain experts (unlikely in a big corporation), they need validation from real paying customers to make sure their prior ideas are beneficial for the customers.

Both these effects caused Core partial-Product development to be organized as a series of projects (called releases). Each project had its defined deliverables (coarse-grained items). To finish a deliverable a series of tasks has been defined. These tasks formed a list that teams used for their Sprint Planning - fake partial-Product Backlog (see Figure 9). Stakeholders were only interested in progress towards finishing these big coarse-grained deliverables.

This stands in stark contrast with a true Product Backlog idea according to Scrum: an ordered list of independent potentially-valuable items that can be finished in one Sprint, which is adapted (items added, removed, changed priority) every Sprint based on learning, and prioritized by a true Product Owner. Why did such deviation happen?

Items in our lists were not independent because each of them belonged to one deliverable - each item was interesting only to the point, to which it contributed to finishing the deliverable. Item independence was not appreciated by anyone in the company. Not by stakeholders (they wanted deliverables), not by PM/BAs (they wanted to finish deliverables to stakeholder’s satisfaction).

For the same reasons the items were typically not small and were often not finished in one Sprint. It didn’t matter whether one item was finished, it mattered how it contributed to finishing the respective deliverable.

Item ordering was not absolute but rather followed a two-dimensional scheme shown in Figure 9. PM/BA had the right to prioritize items in one column, while deliverables were prioritized by the product manager - another indicator that the product manager should become a true Product Owner.

Why did stakeholders want big deliverables? We’ve already mentioned two reasons: big expectations and covering what-if scenarios caused by the six-month long release cycle. Let’s add another important one. In a company with multiple management layers lower and mid-level managers will not have business success of the developed Product as their primary objective (implicit or explicit). In fact, they can’t have business success as their objective, since their scope of influence is just a narrow set of components or a predefined set of items to deliver in “the project” (all part of the Contract Game). So they will focus on “delivering features”, especially if the added feature is clearly visible or its idea can be sold internally in the company. In other words, they prefer predefined big-bang deliverables to small incremental improvements that are adaptively based on learning and feedback.

Focus on big deliverables obviously reduces adaptiveness at a global level. If the delivered items are big, they take longer time to deliver, which delays customer feedback and delays validation of our hypotheses/speculation about customer behavior. Also, implementing bigger items tends to bring more complexity to the Product and codebase which makes further development more costly and further reduces adaptiveness.

Impact of big deliverables on opportunity cost

Big deliverables are also more likely to contain a mixture of probable higher-impact items and probable lower-impact items. Holding shipping of probable higher-impact items until all probable lower-impact items are ready to ship brings opportunity cost to the company. Let’s demonstrate it in an example.

We have a deliverable consisting of two items - I1 and I2. I1 is hypothesized to have impact 100 (imagine e.g. increased sales by $100,000), I2 is hypothesized to have impact 50. Now imagine that there is an item I3 with the hypothesized impact 75 in the backlog and waiting for a team to pick up. If we decide to deliver items I1 and I2 (because they are part of the same deliverable) then our opportunity cost is 75-50 = 25. The bigger the deliverable is, the more likely it is that at least some items in the backlog have higher probable impact than the unfinished parts of the deliverable currently being worked on.

Reducing planning duration and complexity

Six-month release cycle combined with wishlists from multiple groups of stakeholders led to another common problem - to estimate and plan a large number of backlog items in the beginning of the six-month cycle. This was now exacerbated by the fact that there was only one backlog instead of five - the list was much longer and we wanted all teams to participate in estimates and the planning process.

Before the adoption, the estimation and planning process took a significant amount of time and effort. In the further text, we describe two concrete experiments that allowed us to reduce planning overhead (waste from the lean point of view) - using affinity grouping estimates for the backlog and using the “Buy a feature” game for planning with many stakeholders.

Once again though, let us emphasize that this improvement in adaptiveness was relatively minor (an order of magnitude smaller) compared to the situation, when a broadly-defined Product is delivered by feature teams frequently to customers and feedback is gathered directly from customers. Nevertheless, we thought these experiments might be worth sharing because all were triggered and made possible by the fact that we merged three lists into one.

Try … Reduce planning duration by using affinity grouping estimates

Asking for estimates for deliverables took a significant amount of time. How did it work? Deliverable definitions were typically very fuzzy, sometimes as much as “support monitoring of device X”. Engineers did not feel comfortable to provide an estimate for such a fuzzy requirement and asked for research time. “Research” (in fact a synonym for upfront requirement analysis) was planned as a product backlog item for the next Sprint. When the Sprint was over, the outcome of the research was consulted with the stakeholder who requested the feature. This often led to another research item in the next Sprint and so on.

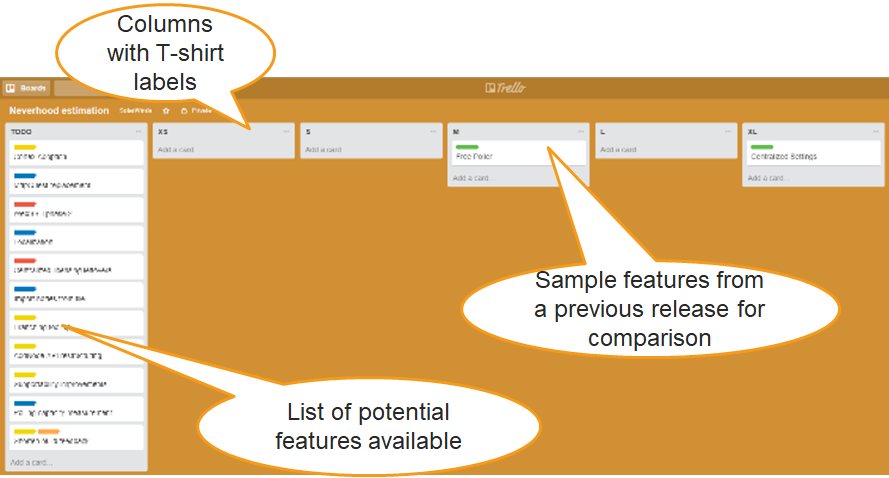

To reduce this ping-pong we asked teams to do a time-boxed one week research on all deliverables given by the business. After this period we organized a one-hour estimation session with representatives from all teams. As a preparation for this session we prepared a Trello board with 5 empty columns (XS - XL) prefilled with examples of features finished in the last six-month cycle. As these items were finished, their size was known so they can be assigned to the appropriate columns (see Figure 10).

The first column of the board was pre-filled with titles of all the coarse-grained items. At the session the team representatives took the trello cards one by one in a round-robin fashion and moved them to the appropriate columns. Always one item was moved by one person. If the next person disagreed he/she can move the already assigned item to a different column instead of assigning a new feature. Finished item served as reference for better comparison especially at the beginning of the session when only a few new items had been assigned.

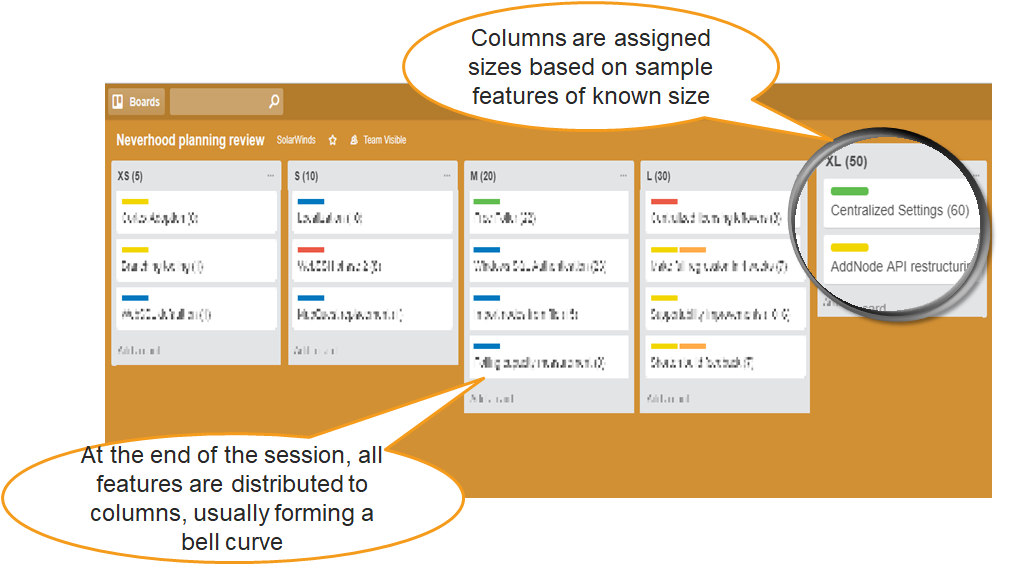

The session typically took about an hour and resulted in an item distribution shown in Figure 11. The columns were then assigned numbers corresponding to the number of fine-grained backlog items corresponding to each deliverable. The number was estimated using the finished-items examples.

We didn’t use story points for individual backlog items, but rather followed the #NoEstimates assumption that all backlog items are of the same size on average, the assumption backed by historical data in our case.

Another observed effect was playing it safe for vague items. For example, the “AddNode API restructuring” item in the picture below ended up in the last column (XL) just because the teams knew nearly nothing about it at the time of estimation. This clearly indicated to the item donors (architects in this case) to communicate more with the teams regarding the item content.

Time-boxing the research and doing all estimations in one hour helped us reduce time needed for the planning phase and the teams could spend more time working on the Product, learning by doing.

Try … Buy a feature game when you have many stakeholders

Even after all items were added to one backlog, stakeholders still looked at some items as “theirs” and pushed hard to have them prioritized over the others. This attitude led to the backlog consisting of items satisfying one particular stakeholder instead of a prioritized list that all stakeholders would agree on.

To break this dynamic we used the Buy a feature game. First, we prepared the list of all features with estimated costs given by the engineering groups, see section Try … Reduce planning duration by using affinity grouping estimates. Second, we gave each stakeholder a certain amount of virtual money. The table could look like this:

| Stakeholder | Jeff | Tom | Kate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget | 60 | 20 | 20 | |

| Feature A | 40 | |||

| Feature B | 25 | |||

| Feature C | 15 | |||

| Feature D | 20 | |||

| Feature E | 50 | |||

| Feature F | 20 |

Then, we organized the session with all stakeholders where they can invest their money into features. At the end of the session the table could look like this.

| Stakeholder | Jeff | Tom | Kate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget | 60 | 20 | 20 | |

| Feature A | 40 | 25 | 15 | |

| Feature B | 25 | 25 | ||

| Feature C | 15 | 10 | 5 | |

| Feature D | 20 | 5 | ||

| Feature E | 50 | |||

| Feature F | 20 | 20 |

In this artificial example, features A, B and F would be planned into the major release, while features C, D and E would be rejected. Sometimes we organized multiple rounds of buying features so that stakeholders could reallocate their money and spend money from rejected features.

Overall this approach brought better transparency to the planning process and less fights between stakeholders (like Jeff and Tom buying feature A together in the example above). However, it also came with some drawbacks. The Contract Game was still here, although in a more collaborative way - stakeholders assumed that what had been bought will be delivered in a six month release. Also it was difficult to set priorities between the accepted (green) features - again, stakeholders assumed that all features would be delivered.

Product broadness effects on team specialization

Before the partial LeSS adoption, teams were used to having the work prepared by multiple PM/BAs. Let’s remember that there were three PM/BAs for five Core teams so one PM/BA typically served 1-2 teams.

The previous paragraph reveals two interesting facts. First, the work items were prepared to be suitable for teams, not individuals - which is consistent with adaptiveness as the highest goal. Second, there were multiple PM/BAs, which led to implicit team specialization. The team specialization did not necessarily respect the component boundaries in the code, but rather boundaries given by the specialization of “their” PM/BA. This kind of single-specialization (even if it is not defined by code boundaries) is not consistent with adaptiveness as the highest goal.

By replacing three PM/BAs with one we removed the boundaries that nudged the teams to single-specialize and opened the path for broader knowledge and flexibility. No strict code ownership policies were in place so we didn’t have to unlearn anything. We also had an advantage of relying on historical knowledge - some team members developed the partial Product for years and remembered times when they were not single-specialized.

Of course, primary tools to nudge teams towards broader knowledge are Sprint Planning with a single backlog and Multi-Team Product Backlog Refinement. We mentioned them in the section Reducing the number of coordinators. Here, we would like to mention two additional elements that supported this process - communities and maintenance.

Communities

The concept of communities was introduced in the company in 2015, about one year before the partial LeSS adoption. Since then several communities have been established (see Figure 12). Examples include: security community, continuous integration community, hiring community, automated testing community, agile club. The communities were typically not limited to Core but spread across the whole company (although they tended to stay in one location). Engineers were actively encouraged by managers to participate in community life. In general, communities helped their members to get inspired from the other teams or groups and often helped them overcome the local mindset and see the whole. Specifically for the members of the Core teams, participating in the community helped them see Core as a part of a bigger system (Orion product development) and reduced their pushback to learn multiple components of Core during their work.

Handling Maintenance Load

The Product we developed historically had a high maintenance load. Why? There are multiple reasons.

First, it has been caused by the nature of the Product. Orion is an on premise software installed at tens of thousands of customer sites in very diverse environments. Although the perceived product quality is high (judging from the very high percentage of customers renewing their paid maintenance support every year) the diversity of environments still brings unexpected situations that cause customers to report problems.

The second reason for high maintenance load is systemic and company-internal. Each customer problem is primarily handled by a representative of a support department, a group separate from engineering. Support reps handle the vast majority of the issues taken, but a minority of the most difficult ones had to be handled by the engineering group.

In the short term this setup looks like a good idea (see Figure 13). The more customer problems are handled by a support group, the less open problems we have, the less support reps we need, which creates a balancing cycle B. There is, however, a strong long-term effect. When customer problems are handled by a group separate from product developers, these developers are unaware of customer problems and it is highly likely that they will develop the Product in a way that customers will not like (at least existing customers). If this dynamic is not understood, it creates a reinforcing cycle R of a growing number of customer problems followed by a growing size of the support group.

As our adoption was only a partial adoption we didn’t address the fundamental problem described above. Our ambition was only to use the engineering effort spent by maintenance as a learning opportunity that will lead to a better understanding of the whole partial Product and therefore more adaptiveness. As a side effect we expected a slight decrease of customer problems reported.

Our starting point was 20% of engineering time spent by working on customer problems. A rotating maintenance duty had been established (based on the Batman idea from The Art of Agile Development book, first edition). Every Sprint one of the five teams had been “sacrificed” and dealt only with so-called customer issues. Two advantages were expected. First, the remaining teams will be shielded from unexpected interruptions and switching context in the Sprint. Second, as customer issues come from all areas of the partial Product, teams will learn the whole partial Product over time which will lead to more informed design and implementation decisions when developing new features.

The number of interruptions slightly decreased, however, the overall situation didn’t improve as the expected learning didn’t happen. Teams hated maintenance duty. In addition to that team members knew they needed to deal with customer issues only once in five Sprints. So the path of least resistance was to delay the customer issue resolution until someone else took over. Several attempts had been made to improve the situation. For example, a group of the most experienced engineers from all teams met every day and discussed the most difficult long-term customer issues. Or we tried to share success stories of fixed customer problems. However, none of these experiments were able to overcome the lack of learning within the teams.

After almost two years of experimenting with rotating maintenance duty teams themselves came up with the idea of splitting the partial Product into parts - each team would specialize in certain partial-Product functions and deal with all customer issues related to these functions. (Let us emphasize here that the split didn’t apply to the partial-Product Backlog - teams were still supposed to implement items according to their priority.) This proposal had been implemented and it led to more learning than before although the learning happens in a limited scope only. Moreover, teams were able to identify problems in their parts of the partial Product faster and propose improvements there.

Interestingly and showing the situational – perhaps even individual – nature of this dynamic, in contrast to the Core group that didn’t (or couldn’t) take advantage from rotating, rotating maintenance duty was successful in other parts of the company. Some smaller groups (up to 4 teams) were able to apply it long-term and it improved their teams’ knowledge of the partial Product. A key difference between these groups and Core is the codebase size and partial-product complexity. Both were an order of magnitude higher for Core so some specialization was probably inevitable, because the cognitive load of understanding the whole partial Product and codebase is too high for the teams.

In future, when introducing specialization we shall avoid the false dichotomy between “every team knows the whole Product” and “every team must be specialized on a few fixed components”. We shall rather consider the cognitive load of developers to be a system constraint and try to support the highest adaptiveness possible while maximizing the constraint. This is the same dynamic that leads to introducing LeSS Huge, where cognitive limits of the Product Owner are usually the limiting factor.

Multiple approaches can be taken that lead to higher adaptiveness than fixed component assignment. For example, if LeSS Huge is used, teams can be responsible for all customer issues in their customer-oriented areas regardless of the components that they need to know to solve them. Or they could use accidental specialization for distributing customer issues as it is used for backlog items.

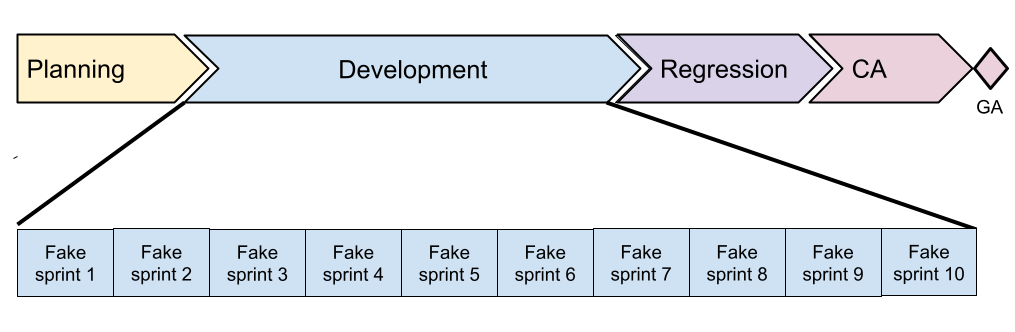

Release frequency

Learning to be potentially able to release software to customers every Sprint is often a major challenge in agile adoptions. When a sequential lifecycle is used, releasing is a big event that requires heroic effort of many individuals and takes weeks if not months (as you can see from the figure below this was also our case). Changing this to frequent releases and following the Guide “Ship at Least Every Sprint” (Book 3) is … difficult. We were not successful in this aspect, mainly because our product definition was too narrow and we had to coordinate releases with other groups in the company.

Still, it might be interesting to share some of the analysis that shows how a long release cycle affected adaptiveness of product development.

Release cycle

Core was released to the public every six months. It had always been released together with NPM - a flagship module. The release cycle consisted of four phases shown in Figure 14. As you can see it is a sequential (waterfall) lifecycle with a typical fake Scrum adoption pattern - using fake “sprints” only for the development (which doesn’t improve adaptiveness), and which violates the very meaning of real Sprint: that each ends in a completely Done Product Increment (including all forms of testing)

- Planning. The goal of the planning was to fix the content of the whole release (See also The Contract Game section).

- Development. Development was organized in two-week fake Sprints that were really just development increments. Software was typically integrated multiple times a day and each Sprint resulted in a build that could be consumed by modules, but it was not potentially shippable (and lots of undone work, such as regression testing, was growing).

- Regression testing. About one month long regression-testing phase where all the previously undone work was planned in order to get the software into a shippable state.

- Customer Acceptance (CA). This one-month phase was used to collect feedback from customers on the new features and overall quality of the Product. It started with a release candidate build given to the customers and ended with the General Availability (GA) milestone.

Historical reasons that prevented more frequent releases

Delivering once in six months is not ideal when optimizing for rapid feedback from customers that tries to invalidate hypothesized customer value. The thinking behind long releases was of course rooted in management conviction that we know what to do and do not need to try to invalidate our hypotheses.

There are two important historical reasons why SolarWinds was able to develop successful products for years despite long sequential release cycles. Let’s summarize them here before we move on.

First, over time the company developed multiple surrogate mechanisms to collect feedback. Product Managers spent hours every week on calls with customers, the company employed UX researchers who gathered feedback on the product usability, customers had an opportunity to upvote features on a community portal and the whole CA phase was focused on collecting feedback from the customers.

Second, the company was implicitly optimized for a six-month release cycle for every product with an online marketing campaign following each public release being the main event. Each campaign drove new sales, maintenance renewals and brand awareness. Six months was determined as an optimal time interval between two subsequent marketing campaigns. With a little exaggeration it can be said that a new product version has always been only a deliverable to the marketing campaign.

Consequences of six-month releases

Long releases of course come with costs. We have already discussed one in the section Coarse-grained prioritization - big deliverables. Big deliverables are a consequence of the need to prepare regular marketing campaigns - it is easier to build marketing around big features rather than around small ones.

As long release is one big (in fact, huge) deliverable itself, it brings all problems described for big deliverables, especially Opportunity cost. We will not repeat the analysis here as it is identical.

Other costs are interesting as well, though, especially the ones that create reinforcing loops. For example, if you ship your Product to customers rarely, you typically don’t care too much about the upgrade experience (because upgrade is a rare event). As a consequence, upgrading a Product is usually a pain. People in the company who have to deal with the customers’ upgrades (for example, in the support group) feel the pain and push for less frequent releases so that they do not need to go through the pain often.

It was the case in our situation. Especially bigger customers had to spend hours, sometimes days upgrading the Product per each new major version released. To revert this trend the company had decided to explicitly invest in improving upgrade experience (one of the so-called “initiatives” in Figure 4), but at the time of this case study this initiative was at its beginning and no improvement in upgrade experience was observed yet.

A lean answer to painful upgrades would be: if it hurts, do it more often. Each public release is an opportunity to identify what exactly makes the customer upgrade experience painful and slow and to address it so that next time they need less time and effort to upgrade. By applying this repeatedly, we would gradually decrease transaction costs of upgrade to (almost) zero that would allow us to upgrade at a whim and (supposedly) earn higher customer satisfaction as a side effect.

Long releasing cycles also led to lack of proper test automation - when you release once in a while it is acceptable to do manual testing. And when you need to use manual testing in order to ship the Product, you don’t want to repeat this effort too often - another reinforcing cycle. In our case, manual testing occupied a major part of the regression-testing phase.

Lack of test automation coverage was exacerbated by the fact that Core was only a partial Product - in order to produce a shippable Product Core group had to coordinate the regression testing with module teams. The coordination and testing of all integration points was a manual activity that required a couple of weeks to finish.

The Contract Game

Long release cycle also led to what is known as The Contract Game (Book 2, Section Thinking About Product Management). The business side of the organization starts with a long list of requirements. The engineering side provides estimates that make it clear that only one third of the requirements can be delivered in the release. The business side is unhappy and asks engineering leaders to deliver more.

Both parties meet several times to discuss various options for increasing the group capacity or changing the scope of individual deliverables (the process called “horse trading” in SolarWinds). The horse trading takes up to two months and consumes a significant amount of the engineering group capacity. After two months nobody is happy but only three months are remaining for development within a six-month-long release cycle so all parties quickly agree on something and the development starts. Of course, no one wants to later revisit the question, “Are we still today doing the most skillful things?” And as a result, resources are spent on outputs for which we usually have only weak speculation, which itself may have become invalidated over time.

Near the end of the cycle engineering realizes that the initial estimates were wrong and another round of negotiation starts. Programmers come with ideas to cut tasks that keep the gist of the big deliverable intact. If they are lucky they will find some. But as the deadline is approaching this is less and less of an option. So programmers look into their secret toolbox and find some magic tools that make the deadline happen with “original scope”. This is the time when they stop refactoring or writing automated tests, do quick fixes of bugs instead of finding root causes and so on.

Try … Regular cumulative service packs to gather customer feedback more frequently

Of course the world doesn’t stop when you spend time planning and “executing” on the long major release. Customers that use your Product discover many ways to improve them. Some of these tasks are very difficult to postpone for 6 months or more. Examples include:

- An important security fix

- A very small improvement that immediately helps close a very large deal

- A bug that affects many customers

- An incompatibility with a new version of another software your Product integrates with

Of course, when shipping to customers every Sprint one can just include all of the above as backlog items and properly prioritize them. With a six-month major release cycle the company used so-called hotfixes to deliver these critical fixes. As we didn’t succeed in shortening the major release cycle (which would be a major improvement towards adaptiveness) we experimented with using hotfixes as a way of collecting feedback and trying to invalidate our hypotheses.

During the partial LeSS adoption we changed the way of releasing hotfixes significantly, in fact turning them into small and regular minor releases.

First, we completely automated hotfix installation (no more copying binaries).

Second, we had made hotfixes cumulative, i.e. every new hotfix had to include everything included in the previous hotfixes. By doing this we increased the chance that problems with combination of fixes will be discovered internally before the hotfix will be released to customers.

Third, we had changed the installer so that it automatically installs the latest cumulative hotfix whenever a customer installs the latest major release. That increased the number of customers with the latest hotfix installed and thus the amount of feedback on changes released in this hotfix.

Fourth, we defined a regular cadence of cumulative hotfixes - one every month.

Fifth, we were able to ship some fixes hidden under feature toggles and enable them for selected customers.

All these changes helped reduce The Contract Game at least for small items. Stakeholders were much more relaxed at the major release planning because they knew they could ship some of the small critical items in regular hotfixes.

Conclusion

This case study describes a partial and incremental LeSS adoption in a multi-component product group that was a part of a larger product suite. We decided to use Core (a large set of low-level components) as an initial Product and proceed with adoption in the corresponding multi-component product group consisting of 5 Teams.

It was a mistake. It constrained our thinking and organizational changes to one big component and kept many mechanisms that prevented adaptiveness in place - component teams, big batch releases, big deliverables and so on. It would have been better to start with all of Orion as an initial Product, take a LeSS Huge approach and incrementally start the adoption in one true customer-oriented Requirement Area.

All that said, “the art of the possible” is an important mindset and behavior in organizational change. We didn’t have the senior management support needed to start in the recommended “top-down and bottom-up” LeSS adoption approach, and so we did what we thought we could, learned a lot from that, and did nudge the organization towards some improvements.

Of course, this key decision allowed us to do only relatively minor improvements towards adaptiveness - reducing the number of fake POs improved Teams’ ability to coordinate, reducing number of backlogs let us reduce the overhead of planning and using a bit broader Product than before helped us reduce Teams single-specialization.

Many aspects affecting adaptiveness remained unchanged though. Component teams (existing due to both lack-of cross-functionality and too narrow product definition) still required a lot of handovers and coordination by managers and other intermediaries. The Product could only be released to customers every six months and each release required a major manual coordination effort. This, too, was a consequence of the initial decision of taking a set of components and calling it a “Product” and we were not able to overcome it even in the years following this case study.

References

I frequently refer to the 3 LeSS books in the text.

Book 1. Craig Larman, Bas Vodde: Scaling Lean & Agile Development: Thinking and Organizational Tools for Large-Scale Scrum, 2008

Book 2. Craig Larman, Bas Vodde: Practices for Scaling Lean & Agile Development: Large, Multisite, and Offshore Product Development with Large-Scale Scrum, 2010

Book 3. Craig Larman, Bas Vodde: Large-Scale Scrum: More with Less, 2016

The other books and resources are directly linked from the text.