Y Soft

Evolving Y Soft’s Organizational Design

Y Soft adopted LeSS in 2019. A differentiator of Y Soft’s LeSS adoption was not only making significant organizational design (OD) changes, but then also changing the changes based on learning. Such changes are a prerequisite for being adaptive and hence making Scrum or LeSS work. Learning and evolving in OD is often needed based on experience. Therefore, a theme of this case study is the evolution of their OD elements in their LeSS journey.

Each section describes an experiment of an OD change in the LeSS adoption. It is structured as:

- Context

- Narrative

- Inspection: reflection on recent OD changes

- Adaptation: changing the changes

My role (Mark - main author) in the LeSS adoption at Y Soft was the on-site coaching and improvement of the LeSS adoption after exactly one year (January 2020) into the LeSS adoption as the only external consultant. After over a year (Spring 2021), it became a more supporting and mentoring role (1-2 days a week) towards the Scrum Masters that support the product and the teams, until summer 2022. The scope of this case study is from the start of the preparation in 2018 until late 2021.

This study ends with interesting but secondary-topic appendices on Y Soft’s related experiments with improving technical excellence, and some key preparation events.

Who’s Y Soft?

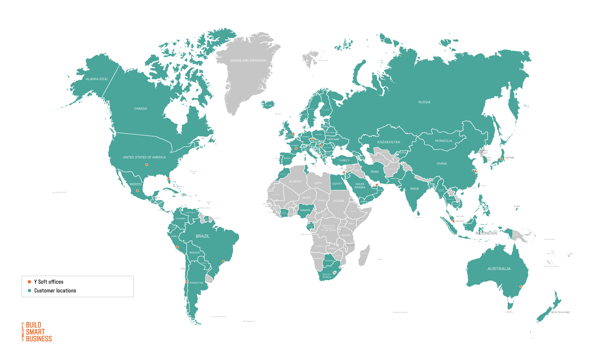

Y Soft is a multinational software and electronic hardware company founded in 2000 operating worldwide. The company’s headquarters are in Brno, Czech Republic with other offices around the world. Y Soft products are enjoyed by over 29,700 customers around the world, including 44% of the Global Fortune 500 companies.

Y Soft’s product development is centered in the Czech Republic with offices in Brno, Prague, Ostrava, but also Copenhagen with 120+ people within Research & Development (R&D), where most of the product development takes place.

Product

This section describes the status of the product involving the LeSS adoption at Y Soft, YSoft SAFEQ, in the timeframe from 2018 to late 2021, for context of this case study. Since then, Y Soft’s portfolio has changed and extended, and Y Soft acquired EveryonePrint in 2022. These developments are not taken into account in this section. For the latest information about Y Soft and its products, visit ysoft.com.

SAFEQ has a series of Print Management solutions for print devices. Big printer vendors have SAFEQ installed on their devices and are in direct contact with customers. For most customers, it’s unknown that they use SAFEQ.

SAFEQ has customers and vendors worldwide and their requirements might be different based on local/country strategies or regulations. Therefore, there is a constant trade-off between implementing features globally or locally and choosing which of those requirements are desired to be in the long-term strategy of the product. One of the key points why vendors & customers want to collaborate with Y Soft is their adaptability and speed to deliver new and innovative features.

SAFEQ complexity comes from different features that different print vendors and customers (in different markets) need. Additionally, vendors are using software in many - sometimes only slightly - different devices. But even small differences in devices have big consequences for the SAFEQ installation. At the time of the case study, most installations for customers are on-premise (note: since then, more and more customers have a cloud-based print management solution), and therefore there is a lot of contact with vendors, and if needed, customers for installation, support etc. Collaboration happens mostly with (local) customer departments, and R&D will be involved when customer departments can’t solve the problems. At the time of the case study, Y Soft is moving to a cloud-based product, which simplifies this complexity.

In the upcoming sections, the different steps of Y Soft’s LeSS journey are explained, step by step from mid 2018 until late 2021. Perhaps there will be a subsequent case study about the steps after this. More info about the latest developments, watch back the Y Soft talk at the 2023 LeSS conference in Berlin.

0. Before the LeSS Adoption

0.1 Context

Coming from waterfall-based product development, Y Soft started trying “agile product delivery”, a name they gave to their new way of working that had little to do with agility or product delivery. They re-organized into 9 component teams with an architect as “Product Owner” per team! it took at least 4 “Sprints” to get one feature delivered, while no team would be able to deliver this feature independently. Note that these were fake “Sprints”, since with component teams (rather than feature teams) the result of a “Sprint” is often just a set of component tasks and hence incomplete features rather than the true intention: a shippable product every Sprint. Many different roles (e.g. project managers, sales, marketing) approached and interrupted developers directly to work on features. To address the challenges with delivering customer features, Y Soft’s Vice President (VP) of R&D installed a product governance committee. They made decisions on product level and decided on features that teams needed to develop. This resulted in a heavily governed process with virtually no adaptiveness, and which didn’t give much transparency to what was going on. Additionally, people that wanted a feature or change used their connections with team managers and developers to get things done outside of the process. This demonstrated that the easy way out (by installing a product governance committee) usually leads back in and probably worsened the situation.

0.2 Narrative

The first attempt of a feature team was in the scanning area of the product, a recognizable area for customers. Two component teams and people from testing & releasing were merged together into one feature team and started something closer to actual Scrum. There were no big organizational changes involved yet, as implicitly required by Scrum, but a few changes were there to enable the team to work this way. This also led to hiring the first Scrum Master that helped in this change. The team did a first attempt for incremental & iterative development with delivery every 1 or 2 Sprints to customers. This enabled the team to work closer with customers. The collaboration helped the team to deliver the right things and avoid building the wrong things, because there was faster feedback and no middlemen in between the developers and customers. There was some increase in adapting based on learning. With this attempt for a feature team, the Head of Product within R&D (who was the manager of the team leads for all SAFEQ teams) also did a minor organizational change in the management structure: instead of three managers (from the two component teams and one testing team) for the new team, he selected one manager for the whole feature team. This was a first shift of management’s behavior towards a more supportive role. The experiment also led to the removal of team lead positions.

The scanning example was thereafter considered “the way to do it” across the entire R&D organization. However, due to the existing structure of the organization, and also the desire of various managers and specialists to stay in their status quo power structures, several critical factors were actually ignored, such as truly cross-component, cross-functional teams. In short, rather than real feature teams, they adopted trivial practice changes rather than the deep organizational design changes that would actually bring a large benefit in terms of adaptiveness, lead time, and customer delight. Therefore only a few minor things improved, and so Y Soft still looked for better ways to address their challenges.

0.2.1 Organizational design elements

Before the LeSS adoption, Y Soft experimented with a few OD elements on a small scale, which didn’t affect the larger organization. These OD elements had some minor effects on the agility, but couldn’t bring the larger impacts without the needed larger OD changes. In short, the OD-elements that were involved in a single experiment with a single team were:

- LeSS Rule: Each team is (1) self-managing, (2) cross-functional, (3) co-located, and (4) long-lived.

- LeSS experiment: Try…Eliminating the ‘Undone’ unit by eliminating ‘Undone’ work

- LeSS experiment: Try…Work redesign

All of these OD elements were limited, because the organization around the single team didn’t change. The team was more cross-functional, co-located and stayed long together. However, it was hard to self-manage, because they couldn’t deliver a working increment without help. And their ability to deliver end-to-end customer-centric features was only from their perspective, but not from the whole product’s perspective. However, from the small perspective they had, there were some minor benefits, work redesign and functions integrated that were organized in an ‘Undone’ unit before for their perspective. More explanation about these OD elements in the OD elements section of the first OD experiment.

0.3 Inspect

The first feature team attempt and the failed expansion feature teams led people in Y Soft to search for additional external information to find out how to move forward with their Scrum adoption(s). They found the first benefits of Scrum, but were unable to gather the benefits that it could bring without the needed organizational changes. They found the LeSS website through Google Search, and people participated in local agile communities and events which led to some genuine interest in LeSS. Especially the presentation by Jürgen De Smet at Agile Prague 2016: “How organizations go nuts” caught their interest in LeSS.

0.4 Adapt

The supporting VP of earlier changes wasn’t completely convinced about LeSS and decided to attend a public Certified LeSS Practitioner (CLP) in February 2018 together with another VP. This became the start of truly considering LeSS as the way forward.

Examining a possible LeSS adoption, the people in Y Soft R&D realized this was a kind of change where they would need external support for. They contacted Jürgen De Smet with a request for collaboration around April 2018, because of their positive experiences from the CLP. Together, they crafted a budget proposal for the LeSS adoption towards the board, including the why of the change and possible success metrics. The board approved the proposal by the end of May 2018, which initiated the LeSS adoption activities to start in June 2018. This led to the preparation of the first major organizational design changes.

1. Experiment 1 Organizational Design: A Single product with feature teams

1.1 Context

The Head of Product decided to start the LeSS adoption and set a time in the future to have a 4-day event to follow the LeSS adoption guide Getting Started and follow the steps of the guide to make a proper start. They called this their ‘LeSS Flip-forward’ event. The Head of Product with product marketing (outside R&D) chose a specific product and clear scope for it to go ‘deep & narrow’, following the LeSS adoption principle deep & narrow over broad & shallow. The 4-day event was used to do the structural change (organizationally & product) at once.

1.2 Narrative

Y Soft senior management chose Co-Learning (today known as Simplification Officers) as their partner in the LeSS adoption. The Y Soft internal supporters (Scrum Masters, developers and some middle managers) that volunteered to help prepare the LeSS adoption and the workshops came together to understand the current situation, challenges and learn what changes are needed (see following sections). This way, the internal people could take ownership of the change itself, which is a key factor of making a successful change and really owning the change. External knowledge is then used as guidance and a knowledge base.

1.2.1 Preparation for the LeSS adoption

An analysis of the Y Soft R&D context from different perspectives started the preparation: organizational, work processes and technical health of the actual code. The goal of the remote preparation is to learn about the current state of Y Soft, to acquire a better understanding for both Y Soft and Co-Learning (as the partner in the LeSS adoption) and to learn together about next steps. In the analysis were taken along:

- Analysis of internal tools like Confluence & ERP for the organizational assessment

- Evaluation of the technical health by analyzing the code, build- and deployment plans, branching strategies and architectural documentation

The technical health evaluation was used to validate and learn with the developers how to improve. An example learning point that developers took, is to make sure that the knowledge of people that are the single points of knowledge (of certain components or technologies) would be spread amongst teams in the team self-design and to make sure team members could learn this knowledge.

The following results from the initial evaluation were addressed in the preparation of the LeSS adoption:

- Many management layers for a reasonably small organization

- No clear Product Owner - there are “team PO’s”, architects and project managers while these roles don’t exist in Scrum

- In a constant state of firefighting and checkbox hunting

- Jira workflows with more status differences than employees working with it

- +/- 75 explicit backlogs

- 898 build plans in total, maximum build time 25 hours, 50 build plans in continuous failure

- Releasing was difficult and took a lot of time, since each team focused on a specific part around (a) component(s)

The results were validated in workshops and taken as preparation for the 4-day event’s workshops.

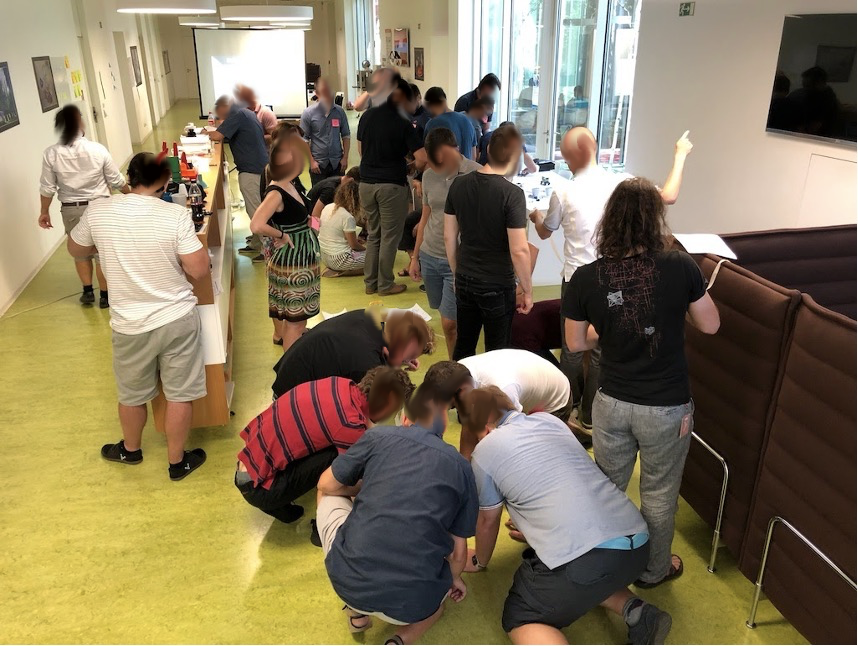

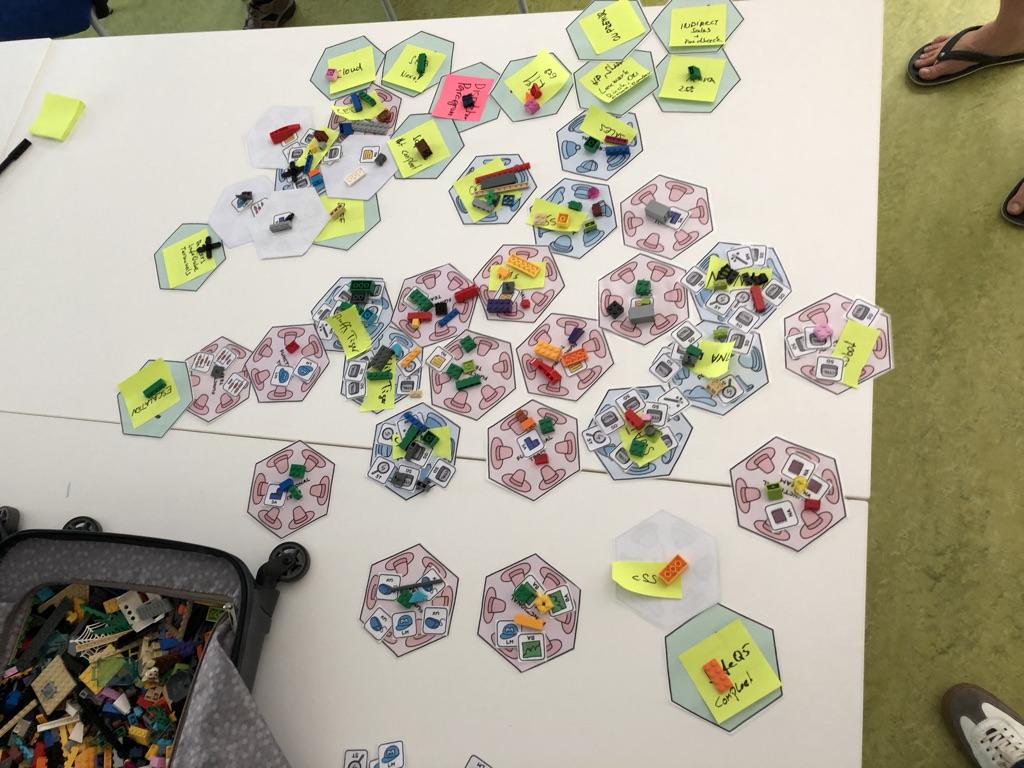

The first step of the LeSS guide Getting Started is: educate everyone. The VP’s and Scrum Masters all joined Jürgen de Smet’s CLP to get a deeper understanding of LeSS. For all developers - and some others - potentially volunteering in the LeSS adoption, there was a Lego 4 Scrum workshop towards a LeSS organization. Jürgen made the workshop very intense, to really get the right volunteers and to know where they would sign up for. Emphasis is to understand it’s extremely important to collaborate with other teams, customers and users.

More elaboration on the preparation for the preparation of the LeSS adoption can be found in this Appendix.

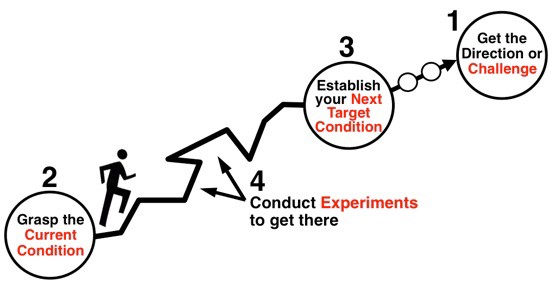

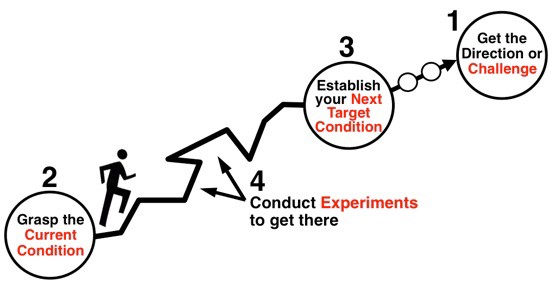

1.2.2 Initial Organizational Improvement Kata (August 2018)

Based on the results from the preparation, an Organizational Improvement Kata was organized, based on the Toyota Kata approach. The direction and challenge that was set forward was to find the optimal organizational structure for starting in the LeSS adoption after the 4-day event.

Positive about the current situation:

- Component focus and deep knowledge of components

- Product is a central point for all requests

- UX & Security knowledge is within R&D

- Focus on support

- Lot of internal knowledge

Improvements for the current situation:

- Teams wait for each other a lot

- The build pipeline doesn’t work well on product level

- Almost no feedback back from the field

- No direct information flow to teams from the field

- Requests that go to the teams are not what the customer actually wanted

- No clarity for roles

- Support interrupts new development

- Escalations go through different channels

- Documentation is not right

A selected group was working to design a future state using the Meddlers Game from Management 3.0. They explored options to elevate the favorable patterns discovered and eliminate most (not to say all) less favorable patterns.

The same group defined together what ‘product’ could mean in the context of the new organizational setup. Define product is the second step in the LeSS guide Getting Started. Volunteers from the ‘educate everyone’ session were added to get feedback on the results for the organizational setup. The whole group did a Feature Team Adoption Map exercise. This LeSS guide Feature Team Adoption Maps helps to make transparent the kind of organizational change you can expect for the LeSS adoption. It’s a representation of the gradually increasing work scope of the teams on one axis and the degree of cross-functionality of teams on the other axis. It resulted in insights on the organizational setup and to set boundaries of what is in scope for the 4-day event that starts the LeSS adoption.

An important observation was that nobody wanted to be the Product Owner for the newly defined product.

More elaboration on the preparation for the preparation of the LeSS adoption can be found in this Appendix.

1.2.3 Preparing the 4-day event starting the LeSS adoption

Within Y Soft, the VP and the Scrum Masters took the lead to further prepare the 4-day event. There was no official change team and the responsibilities for all activities were taken by volunteers. The volunteers met twice a week to synchronize on progress and discuss and plan next steps.

One activity was to set up communities (AKA ‘Communities of Practice’) to be able to coordinate between teams, work together on designs and share knowledge between teams. The LeSS guide Communities is there to address cross-team concerns about e.g. skills, standards, tools and designs. Recommended communities include design/architecture and test. Developers were asked to set up communities they thought were useful, which resulted in many “communities” without any real impact.

Additionally external support was used to organize several in-depth technical workshops. In an event-storming workshop, volunteers linked their (technical) architecture back to business context. Teams had to move from a component focus to a whole-product focus, and these insights helped teams to better understand that whole product. Additionally, there was an internal code retreat on baby-step refactoring to bring in some necessary engineering practices for teams to move ahead. People could use the learnings of this workshop in their teams. This way, they could integrate all components in one product, including support, releasing and other activities.

One of the crucial activities that was needed in the preparation was to find a Product Owner. After searching and discussing this internally, the VP of product marketing took the role of Product Owner, as in the very first Scrum adoption at Easel in 1993. The people in his department from product marketing would help teams to get the needed customer understanding.

More elaboration on the preparation for the preparation of the LeSS adoption can be found in this Appendix.

1.2.4 The 4-day event starting the LeSS adoption

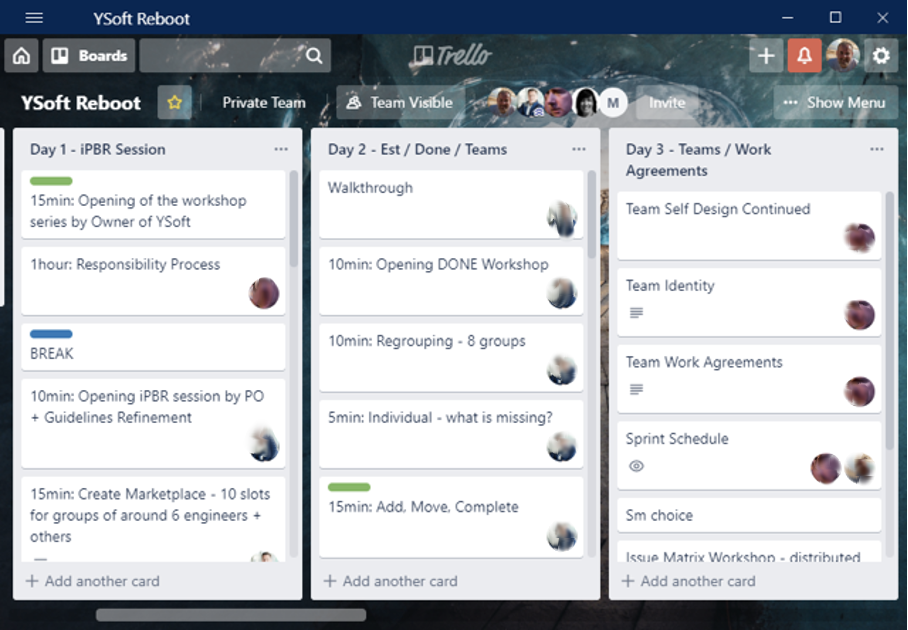

In January of 2019, the 4-day event took place. All possible volunteers would join, including the Product Owner, management and some other supporting roles. The Head of Product explained to everyone the reason for the change in the introduction.

Day 1: initial Product Backlog Refinement (initial PBR)

The Product Owner shared the product vision as a starting point for initial Product Backlog Refinement. The LeSS guide Initial PBR is to make sure that teams have a Product Backlog with enough understood items to start working. It’s important to do at the start of a LeSS adoption, because usually the so-called “Product Backlogs” that exist follow the old structure, often functional or component focused instead of customer-focused. With feature teams, the Product Backlog Items (PBI’s) will be customer-focused and therefore the old “Product Backlogs” will often not be useful, but can be a good source for the initial PBR. Among several other reasons why initial PBR is important, it’s needed to make sure teams understand the PBI’s, instead of having PBI’s written down by one person, team or someone else and assuming others understand it.

The product vision was the starting point for the initial PBR, done together by all participants. Engineers created a marketplace, and worked together with around 6 people per item. People worked in several iterations, and after each iteration, people shared the results to each other in something like a LeSS Sprint Review Bazaar, but only for item analysis, not for done features. After the Refinement iterations, groups of people did ‘mob documenting’, where they added the results of the Refinement to the Wiki and the Product Backlog. After this, the group did estimation on the refinement PBI’s.

More elaboration on the activities of the 4-day event can be found in this Appendix.

Day 2: Creating the Definition of Done & self-design the team

Everyone participated in a Definition of Done workshop, to get to a common Definition of Done (DoD) for the product. According to the LeSS guide Creating the Definition of Done, it was created before the first Sprint started. Participants re-grouped and with facilitation techniques from the LeSS guide Cross-Team Meetings, the entire group ended up with 1 DoD with diverge-merge cycles.

After that, they did an ‘undone’ workshop to discover which activities can be done each Sprint (following the LeSS guide Creating the Definition of Done). People divided activities that weren’t on the DoD - meaning teams weren’t able to get that ‘done’ - into the groups. Each group defined how the activities will get done (when, where & what) to identify all the missing pieces to get to a ‘perfect’ DoD and to be able to ship the product to customers. Teams would use this Definition of Undone to improve the DoD in the future. It gave teams transparency with whom to collaborate closely about what. This gave the teams insight into how to deal with (certain types of) ‘undone’ work and what opportunities there are to improve the DoD in the future.

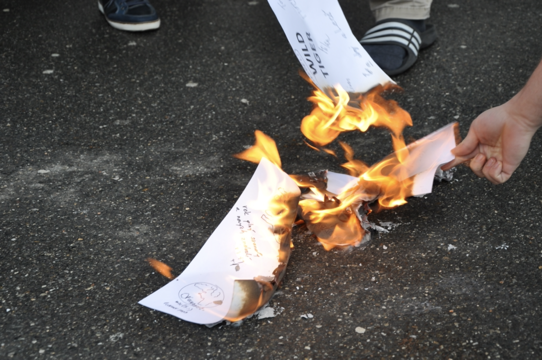

Then, people ‘burned’ their old teams. Teams made materials about their current teams and what it meant to them. They literally burned these materials, as a way of saying goodbye to the old teams and being able to design the new teams with a fresh mind.

Then, the team self-design workshop started. One of the LeSS adoption principles is Use volunteering, to engage people and it gives people the feeling of being empowered. An important part of this is to self-design the teams, meaning to let people decide themselves how the team looks like. The criteria for the self-design for the teams were:

- Team is co-located

- Size is between 6 and 10 people

- Being able to deliver as much PBI’s independently as possible

- High diversity of skills and personalities

Before starting the workshop, it was announced that only volunteers that want to be a team member (following the Use Volunteering adoption principle), Scrum Masters and managers could stay in the room, because they are the ones that are going to work together primarily in the new setting. All other people were requested to leave. Some architects were leaving and decided not to be part of a team. Each volunteer filled in a template ‘personal character sheet’. They included personal skills, technology skills and other important things that they wanted to add to their sheet. This sheet was used in each iteration of the team self-design subsequently. After three iterations, all team members were at least ‘ok’ with the team setup and that meant that the initial teams were final.

More elaboration on the activities of the 4-day event can be found in this Appendix.

Day 3: Team agreements & follow-up with teams

Teams started day 3 with the final iteration of self-design. After the team self-design, teams worked on several things to get to some team agreements:

- Team name

- Team song

- Guiding principles to weigh options and make decisions

- Potential struggles for the team and how to cope with that

- Work agreements

The teams were also able to choose a Scrum Master from the group of Scrum Masters (constraint: co-located). After that, each team did a Done/Undone review in its team, to learn which parts of the DoD they were able to deliver and where they should improve.

Then, participants discussed the support for the product. Besides customer features, there will be other types of work, often bugs or defects coming in, often ‘sudden’ and not plannable. A support department within Y Soft takes care of first, second and third level support of the product, directly with customers. If the support department can’t fix the problem for the customer or needs R&D for that, they create a ‘level 4’ support ticket that is handled by R&D (meaning: the teams). The newly formed teams decided that one team per Sprint takes care of these level 4 support tickets and works with the support department (and customers sometimes) to fix these problems. This team is the fast-response team from the LeSS guide Handling Special Items, that enables a rotating responsibility shared among the teams for support and gives the other teams focus. Because the teams in the old structure were component focused and handled this support separately, for many teams it meant that they didn’t have the knowledge to support all tickets, and as a consequence they needed to learn that.

More elaboration on the activities of the 4-day event can be found in this Appendix.

Day 4: Sprint Planning

On the last day of the event, teams did their first Sprint Planning One in the new setup, following the LeSS guide Sprint Planning One. Jürgen explained the purpose of the Sprint Planning and the guidelines of the Sprint Planning. The Product Owner opened the Sprint Planning by explaining the priorities from his perspective.

Each team shared which availability they had for the upcoming Sprint (holidays, meetings etc.) and the things they needed to finish that were already in progress. Additionally, they added bugs to solve. Then, there was a bazaar for teams to share their selection and design of their Sprint, for the PBI’s they picked themselves. These PBI’s were printed so teams could grab them to select and discuss with other teams who would pick which PBI.

In the next step, each team crafted a Sprint Goal individually. Then, all Sprint Goals were collected and there was an agreement on an Overall Sprint Goal for all teams combined for the upcoming Sprint. Important to mention is that LeSS - in contrast to Scrum - doesn’t require a Sprint Goal. When useful and when there is a natural clear overall goal, it’s good to apply. But when there isn’t a natural clear overall goal (e.g. because of the heterogeneity of work across teams), then it’s better to not have a common Sprint Goal.

Each team selected the - printed - PBI’s they want to work on into their Sprint Backlog (magic whitepaper on the wall) in their team space in the room. In the LeSS guide Multi-Team Sprint Planning Two, it’s emphasized to have the Sprint Planning Two in the same room with all teams, to be able to coordinate with other teams using the ‘just talk’ or ‘just scream’ technique.

Team members looked at the selection of other teams with the instruction to minimize dependencies between teams and move things from teams to other teams. In LeSS, there are no dependencies, because each feature team has the necessary knowledge and skills to complete an end-to-end customer-centric feature. If not, the team is expected to learn or acquire the needed knowledge and skill. The teams were new, and therefore some features didn’t have teams yet with all the knowledge and skills to deliver it end-to-end. In Sprint Planning Two, the teams coordinated between each other how to deliver the features end-to-end, with help from knowledge and skills from other teams if needed, preferably by learning them. This way, there is no dependency, because the teams together - at the same time - make sure the features get done. In hindsight, the instruction to minimize dependencies might have given the wrong perception to teams, because the focus should be on learning or acquiring the knowledge and skills, by working together with the other teams. And these are not dependencies, but simply working together to learn and get features done. Over time, that should have eliminated the perception of having dependencies, by giving the right message.

At the end, all participants celebrated with a dancing challenge! And from that moment the new teams would start working together in the new structure.

More elaboration on the activities of the 4-day event can be found in this Appendix.

1.2.5 Organizational Design elements

A summary and short elaboration of the OD-elements that were involved in the OD experiment:

- LeSS rule: Structure the organization using real teams as the basic organizational building block.

Products are created by teams, while traditional organizations are built around individual accountability. Individual accountability doesn’t promote well-functioning teams that take a shared responsibility to achieve their goal. That’s why an important OD-element is to structure the organization around (real) teams and thus the LeSS guide: Build Team-Based Organizations. Building your organizations around teams has significant implications. Teams are the primary go to for work, rather than individuals, which also means that individuals are not shifted and ‘resourced’ through the organization. This also means that work goes to teams, instead of individuals. As a consequence, the organizational structure will stay (much more) stable and doesn’t need to be restructured, with all of its negative consequences. These teams form around customer value, not around sub-products or organizational functions. Many organizations are organized by functions, and in that case, the implications are big. Before the LeSS adoption, Y Soft experimented with cross-functional teams, but didn’t change their R&D organization yet this way. From the start of the LeSS adoption, teams became the building block for the product. The exception were the Architects and the UX specialists, who were still outside of the teams in the LeSS adoption.

- LeSS rule: Each team is (1) self-managing, (2) cross-functional, (3) co-located, and (4) long-lived.

As a corollary to the previous OD-element, LeSS defined what it means to be a team. Some interpretations of a team won’t give the benefits the team-based organization should bring. Therefore teams are self-managing, cross-functional, co-located and long-lived. Additionally - perhaps unnecessary - each team member is dedicated 100% of this time to one and only one team. The teams need to have the (functional) skills to produce a shippable product (and improve the cross-functionality over time). Long-lived teams need to have stability if you want them to care about how they work as a team. The teams within R&D redesigned themselves into cross-functional teams, at one location and these teams stayed together for a long time (exceptions are natural changes like people moving). Over time, the teams learned to self-manage more. However, this improved especially in the second OD experiment, when additional OD changes were made, more about that in upcoming sections.

- LeSS rule: The majority of the teams are customer-focused feature teams.

Creating Feature Teams according to the LeSS guide Understanding Feature Teams, means that the team organize around customer value and specialize in customer domain instead of technological domain (technological specialization is an accidental specialization as it follows the customer-focus). A Feature Team is a stable, long-lived team with the necessary knowledge and skills to complete an end-to-end customer-centric feature. If not, the team is expected to learn or acquire the needed knowledge and skill. This doesn’t mean that every team can deliver every feature. For example, a big feature is splitted into customer-centric parts (instead of component or technology parts) and delivered by - often - different Feature Teams. Each team can deliver that feature (or learns or acquires to do so). In the LeSS Adoption Principle Use Volunteering, teams can be formed by self-design to redesign the existing teams into Feature Teams. Another option is to grow the scope and cross-functionality over time, for example using the Feature Team Adoption Map (LeSS guide). This way, the teams over time grow to Feature Teams. The teams working for the product redesigned themselves at the start of the LeSS adoption to become cross-functional and customer-focused. They optimized to have as many skills in their team as possible. More about that in the inspection section.

- LeSS rule: The definition of product should be as broad and end-user/customer centric as is practical. Over time, the definition of product might expand. Broader definitions are preferred.

Before the start of the LeSS adoption the ‘products’ were architectural parts of the whole products, each with a team focusing on one part of the architecture. After deciding to start a LeSS adoption, and in preparation of the LeSS adoption, in the organizational improvement kata workshop the participants defined the product definition together. The initial product definition was the whole product - SAFEQ - and all architectural parts of it, except for the infrastructure. Additionally, all surrounding functions were included in the product definition, e.g. the support duty, regression testing and releasing the product. This included the largest part of the R&D department, and as SAFEQ was at the time the main product of the company, it affected the collaboration with most other departments of Y Soft. A broad product definition, which couldn’t be more end-user/customer centric.

- LeSS experiment: Try…Eliminating the ‘Undone’ unit by eliminating ‘Undone’ work

Having an ‘Undone’ unit (Y Soft had a test & release team) delays creating a done increment, delays learning and feedback and removes responsibility from teams. Therefore, the ‘Undone’ units should be removed. Most significant ‘Undone’ unit within Y Soft was the test & release team. In the team self-design, the people from the test & release team joined the feature teams. Teams made the agreement to have teams rotate for creating releases (per release) and support duty (per Sprint). This team is the fast-response team from the LeSS guide Handling Special Items, that enables a rotating responsibility shared among the teams for support and gives the other teams focus.

This removed bottlenecks and created big improvements on shared ‘processes’, like support, fixing bugs, regression testing and the releasing of the product. Teams learned a lot to accomplish this (and needed to teach and help each other), and after a year most teams could do most of these ‘processes’. Additionally, teams improved a lot in these processes, because they are responsible for them throughout the whole product now. It felt sometimes painful and was a lot of effort and mistakes were sometimes made, so the implications were not small. However, teams learned to know the whole product better and shared responsibility.

- LeSS experiment: Avoid…Functional units

Many organizations are structured around functional specializations like test, development, architecture and product marketing. These functional units lead to local optimization with limited perspective for the functional specialists. Instead, have the (cross-functional) teams as the organizational units. In Y Soft’s case, before the LeSS adoption, there were functional units within R&D with (middle) managers responsible for testing, development, architecture etc. In the restructuring at the time of the LeSS adoption, the managers became manager of a few (cross-functional) teams. The only exceptions were security and architecture, but the architects decided not to take part in the teams (yet). The security specialists did take place in teams, but were also very active to spread the security knowledge to teams without security specialists, which limited the local optimization for security.

- LeSS experiment: Try…Work redesign

In Scrum, teams finish complete customer-centric Product Backlog Items each iteration. This has a big impact on the organization of work, but also at the design of the work. Important in this is to design the work with broader responsibilities for teams from a customer perspective. As a logical consequence of having component teams, the work design within Y Soft was focused on components, technology and functions. When starting the LeSS adoption, the work was redesigned to cover customer-centric Product Backlog Items, combining tasks (of different components and functions) in the feature teams.

Inspecting at the organization design principles from the LeSS principle More with LeSS:

We use the following organizational design principles to descale into LeSS organizations:

- From Specialist Roles to Teams: teams became the organizational building block. Over time, specialists in certain (mostly technological) domains shared their knowledge within and outside their team, so teams would gain that knowledge instead of relying on individual specialists.

- From Resource-Thinking to People-Thinking: the building block of the organization became teams and individual performance appraisals changed to team feedback. There was still a desire to add ‘capacity’ in the form of full teams, which suggests still some Resource-Thinking and over time this is something that slowly improved to more People-Thinking. One example of People-thinking is that the CEO found out that the compensations were below average compared to the market, and he increased the compensations massively for everyone in R&D to get above average.

- From Organizing around Technology to Organizing around Customer Value: teams became feature teams working on customer-centric Product Backlog Items. Technology was obviously still important, but specialism was shared within and amongst teams.

- From Independent Teams to Continuous Cross-team Cooperation: the LeSS adoption improved the cross-team cooperation and transparency on what’s going on. After the start of the LeSS adoption, there was more cooperation, but real and more continuous cooperation took a while to learn.

- From Coordinate to Integrate to Coordination through Integration: this was still a challenge, see also this section. Because teams became responsible for all product-related work, they started improving the preconditions and behavior to integrate continuously.

- From Projects to Products: for R&D there were no more projects and all work came from a single Product Backlog. Though there were projects outside R&D, they had limited impact on the teams, sometimes there were PBI’s on the Product Backlog that originated from a project. These projects were used for e.g. marketing.

- From Many Small Products to a Few Broad Products: instead of having component teams working on specific components and functional teams working on functions, the definition of the single product was redefined to one with many teams working on the same product. A good first step moving from many small products to one broad product. Outside this product, there were some other (still small) products in the company, but the product was the main product for Y Soft at the time.

1.3 Inspect

In this section, there is an inspection on the Organizational Design (OD) experiment by looking at the OD changes and the LeSS adoption. First, a generic inspection, and later an inspection on the OD-elements that were changed with the start of the LeSS adoption.

1.3.1 Generic inspection of the first OD experiment

Y Soft experienced big benefits from the LeSS adoption, even though the first 3 months were bumpy and considered ‘painful’ (see below). First, all the future work was collected in one Product Backlog and was prioritized by a single Product Owner. Though this wasn’t perfect yet, teams had more clarity about priorities and could make decisions easier themselves. Second, teams were better able to see and understand the whole product, and additionally able to deliver customer centric features more end-to-end than before. Third, there were less queues and waiting time because of the improved cross-functionality and cross-component nature of teams and the shared responsibility of teams. This is the fourth main benefit: removed bottlenecks and improvements on shared ‘processes’, like executing regression tests, solving bugs, having support duty and releasing the product. More reflection on the last point is in this section.

After the start of the LeSS adoption, the newly formed feature teams started working in the first Sprint. Teams were delivering whole features end-to-end. These features were more customer-centric (though not perfect yet). For the rest of the organization, R&D was less of a black box, because of the higher transparency of the Product Backlog and what the teams were working on. Stakeholders within Y Soft had better understanding of what was developed and could better use this in their work, e.g. in communication with customers (for e.g. product marketing).

Y Soft already had a high customer focus: customer requests are taken seriously, get priority and the collaboration with ‘vendors’ (the partners that sell the printers with the print management solution of Y Soft embedded) is intensive. People in Y Soft are passionate about the product and eager to move things forward and deliver value to customers. After the start of the LeSS adoption, teams got more in direct touch with customers and vendors, because they were working on customer-centric features instead of component requirements.

However, the transparency of the old pains also had a downside, a very predictable one familiar to groups adopting Scrum: some people blamed the new way of working and LeSS for these pains. People needed to share their knowledge with other people for whole product knowledge (which some people didn’t like), people had to do regression testing while they didn’t have to do that before, doing Product Backlog Refinement together while before some people created requirements etc. Instead of working to improve the system, the blaming prevailed. This was reinforced by some of the managers of the teams that were focusing on “efficiency” and output (not outcome), and they pushed teams into doing the things fast, and not always focusing on quality and improving the product. And that pushing of course was driven by historic “efficiency and output” management measurement and bonuses, which were removed, but people didn’t change their behavior based on that yet. However, there was still focus of top management on so-called “velocity”, the amount of work that teams did in a Sprint. That continued this behavior initially, even though there were no bonuses attached to it. Later, when things settled down and the new Product Owner (see this section) came, slowly the feeling of teams to get pressured decreased.

All in all, the first Sprints were described as ‘painful’, but they brought a lot of transparency to continue working on improvement. With some external support, the Head of Product and the Scrum Masters kept working on improving product development further, which was a bumpy ride.

After a few months, there seemed to be a lot of improvements in the product development. Though value was still not measured, the output and predictability of teams had grown massively. Teams felt this as important improvements for themselves, even though output (vs outcome) is not important if it doesn’t bring value and doesn’t contribute directly to adaptiveness. Some other signs that felt like improvements:

- Customers and vendors directly involved in some of the main features.

- Internal stakeholders showed gratitude for better results on developing features.

- Internal stakeholders worked more closely with teams.

- More interactive PBR with more sharing and learning between teams.

- More transparency on the Product Backlog and more explicit - and hard - decisions taken on the priority of features.

- Teams were visibly happier about the way of working.

Though most teams were happier, Y Soft lost around 20% of the people in the first year of the LeSS adoption. People might have felt forced into the change to LeSS, instead of being a volunteer. As the product is the one big product of the company, there were limited options to move to other parts of the organization. Communicating well about the real option of volunteering and setting expectations with people well, could have prevented part of the people leaving. Note: later the CEO found out that the compensations were below average compared to the market, and he increased the compensations massively for everyone in R&D to get above average. For some people leaving, compensation was the reason they mentioned.

Re-Alignment Workshop

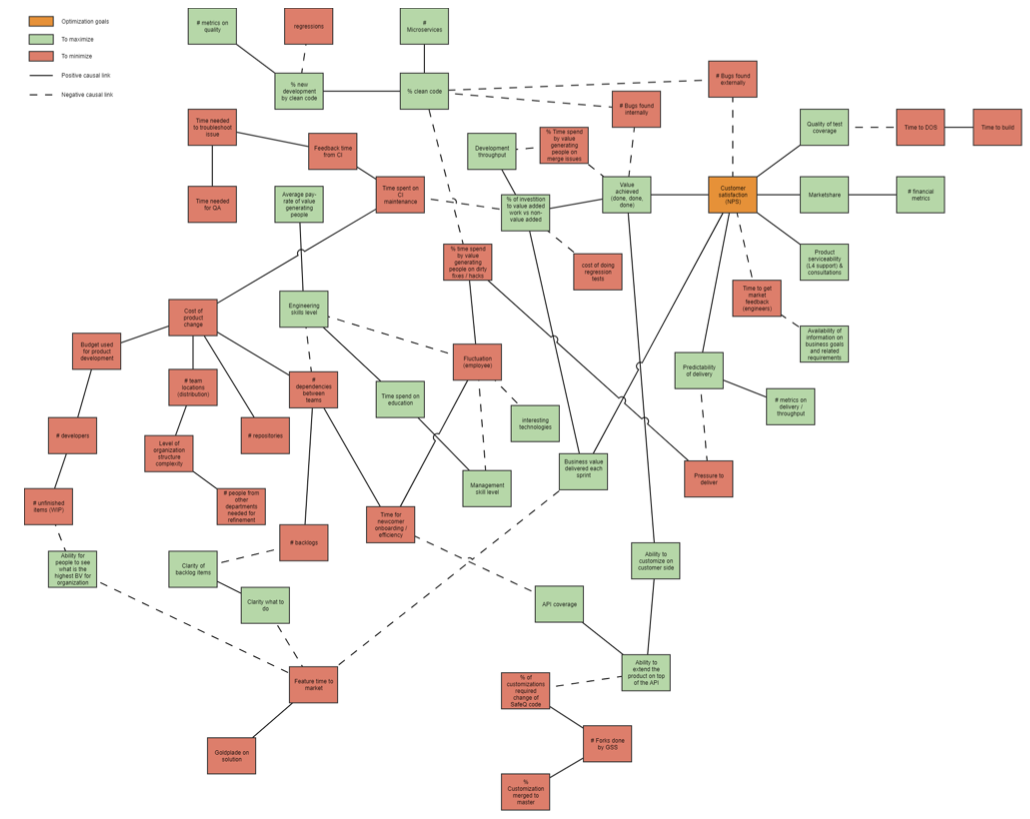

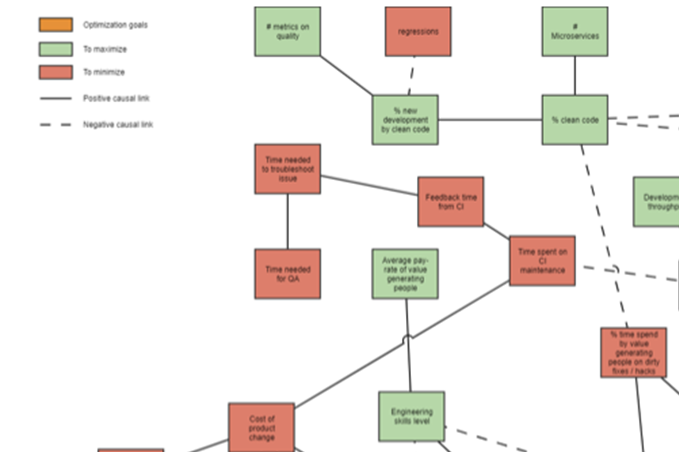

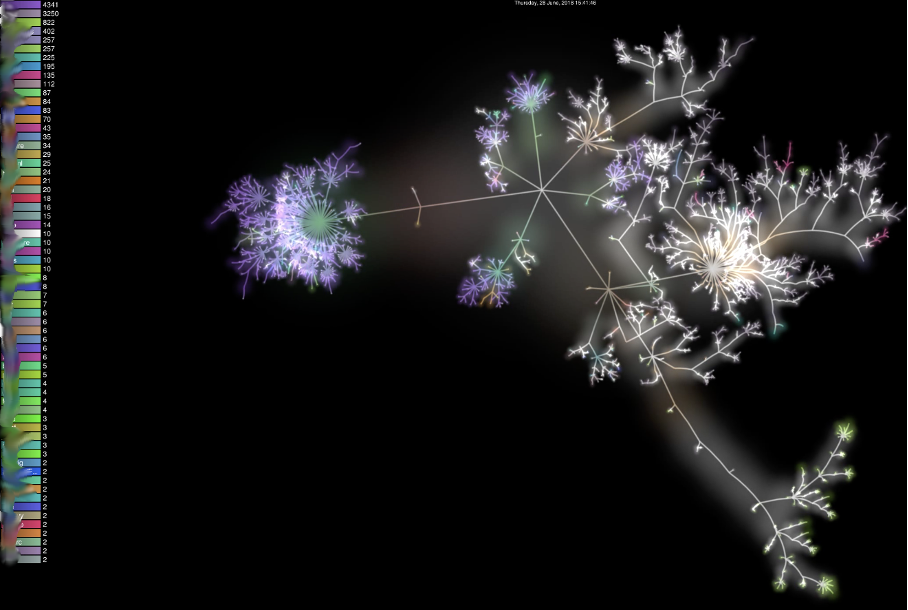

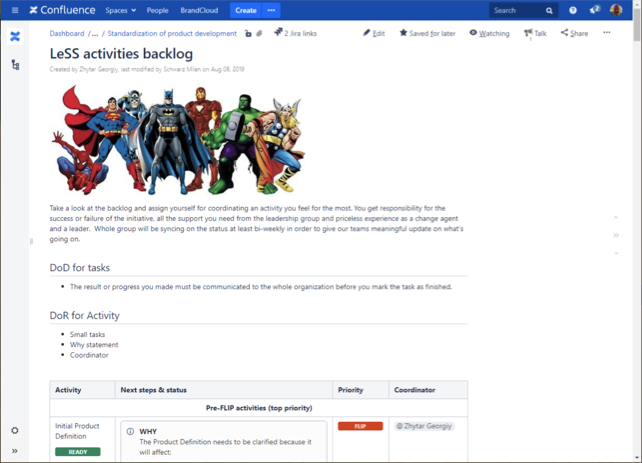

After a few months, Y Soft realized that they needed help with their LeSS adoption. They asked Jürgen De Smet to do a series of workshops to inspect the LeSS adoption, improve further and help prepare for a future move to LeSS Huge. The first of these workshops was a re-alignment workshop to get a better understanding of the organizational system and be able to determine which system variables to improve. The CEO, Head of Product, R&D management and Scrum Master representatives participated in this workshop.

The participants created a system model (causal loop diagram) and identified trend metrics to regularly evaluate whether actions done would lead to overall system improvements. Some of the main metrics to evaluate that came out of this workshop were:

- Time to merge pull request

- Ratio features vs other types of PBI’s

- Time to fix broken builds

- Time to fix bugs

- Estimated business value per Sprint

- Work satisfaction

- Predictability of Sprint delivery

- Predictability of Release delivery

The resulting causal loop diagram:

Zoomed in on a part of the diagram:

The result of the workshop and the system metrics led to better understanding. They collected many of the insights for a while, but didn’t focus on shared understanding to really improve them. The metrics the participants chose to focus on were mostly ‘predictability of Sprint delivery’, ‘ratio features vs other types of PBI’s’ and ‘time to merge pull requests’. Teams used especially the first two often to check progress and identify further improvements. Note that the predictability metrics are not what is desired in Scrum and LeSS, because the optimization goal is to be adaptive to discover highest customer value or delight, which in some cases is the opposite of predictability. The need for predictability also originated from the past, where customer requests and agreements were not met for all sorts of reasons. Product marketing and the CEO wanted more predictability to be better able to make agreements with customers. There was no pressure from them to have it as soon as possible, as long as the delivery would be at the time (or earlier) they set together. Since the LeSS adoption, teams set the expected dates of delivery, in contrast to the previous project manager set deadlines. The intention of the workshop was to let the people from Y Soft find out their own metrics, and little emphasis was on the discussion of the results of metrics.

The results from the product development system dynamics modeling were used as the foundation for the follow-up workshop on maturity models and creating a new organizational design. The follow-up workshop was an Improvement Kata workshop to identify steps to the next target condition.

Engineers, Scrum Masters and management participated in the two-day maturity model workshop. The mixed group of participants defined a definition of ‘maturity’ in Y Soft context, and identified which roles and elements are relevant for maturity models. This led to several maturity models for the categories:

- Empowered self-driven teams

- Product Backlog

- Scrum Masters

- Managers

- Technical excellence

The participants defined areas for each category. For example, for the category ‘empowered self-driven teams’, the participants defined areas like ‘engineering skill level’ and ‘process customer feedback’. For each area, they described the definition of the five maturity levels. For example the description of level 3 of ‘engineering skill level’ was described as: ‘delivering features by our design: We are able to design and deliver the feature on our own. Where the team includes novices, they are appropriately supported (but not supervised or checked constantly) and their development planned.’

The CEO, Head of Product, middle management of R&D and one Scrum Master discussed the resulting maturity models. An external consultant did an analysis of the current state (for each category). In the preparation, the Scrum Masters used the outcomes of previous workshops and this analysis to select several topics to discuss with the CEO, Head of Product and management:

- Organizational structure (including LeSS Huge)

- Product and product area definition and setup (incl backlogs)

- Roles & responsibilities within this structure

- Communities

- Enablers to become technology leader

- Information flow and availability within the structure

- KPI structures

The group improved some of these topics after the discussion. One of the improvements was the dissolution of the architectural team, and instead architects joining the teams. This inspection led to improvements in the current OD and LeSS adoption.

The CEO goes to Gemba and Blogs

One of the teams in Prague invited the CEO to participate for two full days to work with them. In those two days, he joined all their meetings and participated in mob programming sessions (including coding, he started developing the product himself when he founded the company) to do actual product development.

Some highlights from his blog to the whole company about these two days:

‘After some time, I feel I have information worth sharing with everyone.’ […]

‘I welcomed the initiative of the <removed team name> team from Prague’s R&D office to join them for a couple of days. I thought becoming an engineer (again) for two days would not only be fun, but it can also help me to explain some reasons, why we aren’t more efficient. It was actually even a greater experience than I expected, so I decided to share my experience and findings with the entire world.’ […]

Day 1

‘The first day we were troubleshooting a defect in <name of component and what it does>. After upgrade to a new version of the tool, it seemed that some additional configuration needs to happen before the backup can be launched. We used a technique called Mob Programming. We had about 6 people in the team, one computer and each 15 minutes, we changed who is sitting behind the keyboard. At the beginning, I thought it was very inefficient and I was pretty sure, that just two people working on it would be much faster. After two hours I realized, that thanks to the technique, the whole team – who was not familiar with the part of SAFEQ we’ve been troubleshooting – gained the knowledge and experience about it. Even I, who never seen the installation tool called <name> before, was able to write code pretty fast. I would never believe that I can actually contribute this fast, but thanks to the mobbing I learnt so quick.’ […]

‘What really made my day was when I challenged the team, that just fixing a defect will not improve customer experience. The team actually took it seriously and added an incremental improvement: once <tool> is installed, now it will be automatically configured for the database. This is the right way, how we should work: when we are fixing something, we should always ask, how can we improve customers’ life? But that’s not all. The team also took the <tool> configuration files and put them under standard source code control, which will make it very easy for future changes. So the code is now a little bit cleaner. Again, small quick improvement. But if we do small, insignificant, improvement with every defect we fix, SAFEQ will become significantly better.’

‘To sum up my key takeaways:

- Mob Programming should be used more often as a learning technique or to fast-track newcomers.

- Lot of different tools lead to massive inefficiencies. We need efforts to simplify and better document, how are we using them (especially the tools that are use rather sporadically)

- It is possible to bring small improvements with small bug fixes and improve the life of SAFEQ users and admin.’

Day 2

‘We started with a refinement session. The purpose of it is to dive deeper into a certain topic and refine how it delivers value, what needs to happen and estimate efforts. These inputs are later used by product marketing for roadmap planning. The main takeaway was that there is not enough business knowledge. The teams did not have a clear idea, why <topic> is important.’ […]

‘When the refinement session had at least one knowledgeable person (<example topic>), the meeting was very productive and it also helped many people to get acquainted with the specific problem. The estimation process was constructive and efficient. Good experience.’

‘After that I took regression testing of <part of product>. The process was well documented, but troubles with

‘I took a short nap in the train dreaming about the day, when our engineers won’t need to do simple admin steps with no value add because even <component name> regression will be automated. Afterall, the whole IT industry is about automation, isn’t it?’

‘Key takeaways from day 2 are:

- Refinements significantly improved, but only if knowledgeable people are present

- We don’t have enough understanding how Epics deliver value and how important they are

- We improved a lot with automation, but we are still spending significant time on manual testing (but it is now improved in order of magnitudes compared to where we’ve been a year ago).’

1.3.2 Inspection OD-element: LeSS Rule: Structure the organization using real teams as the basic organizational building block.

From the 4-day event that started the LeSS adoption, there was a single Product Backlog and teams directly selecting work from the Product Backlog. To enable the teams to select this work following customer value and knowing what (skills) to learn, it became very transparent that the product strategy and vision was too weak. For example, during Product Backlog Refinement the Product Owner couldn’t explain well what was needed and even during refinement priority changed sometimes. People in Y Soft were used to working in projects and split the work into functional and component tasks for different groups. Working from a product perspective was a massive change for product marketing, the Product Owner and the rest of the organization. Having teams as building block required this, and the Scrum Masters and VP had underestimated the effect of having teams as building block and a weak product vision.

Many people outside R&D still used unofficial communication channels to get work done from R&D, e.g. people from other departments that still contacted engineers directly. This was reinforced by some of the R&D managers that accepted this and even brought this work to the teams! Scrum Masters needed to make sure others understood they had to work with the PO directly to get work prioritized (and why work was not picked up based on priority), and that stakeholders had to help teams directly to make sure teams understood the context and value. The OD change took a while to work properly.

1.3.3 Inspection OD-element: LeSS Rule: Each team is (1) self-managing, (2) cross-functional, (3) co-located, and (4) long-lived.

The teams had self-designed themselves at the start of the LeSS adoption, they were co-located, stayed together and had most of the (cross) functional skills they needed or acquired the skills. The self-management was harder to achieve. Work was defined customer-centric and teams had more end-to-end skills to get work done. However, they still hold on to reactive behavior for work to be done, improve and make sure things get to done. Because they had more of the necessary skills, it automatically became easier, but there was not more improvement.

One of the reasons was that some basic Scrum principles were not implemented well, a consequence from having inexperienced Scrum Masters in Scrum and LeSS adoptions. This resulted in low empiricism and limited learning within and between teams. For example, in Sprint Planning there was low transparency on the work to be done, and little interaction between teams to come up with the best selection of value for the Sprint. A rotating Scrum Master ‘led’ the Sprint Planning and most team representatives just wanted the Sprint Planning to be over. Consequence was that there was limited transparency on the value to deliver and the choices made, which led to little interaction and almost no discussion on what best to do next. Another example was the Sprint Review, which were basically demo’s where teams shared some of the delivered features, without feedback and without transparency about the whole product Increment. Limited number of internal stakeholders joined, and there was no transparency - and thus no inspection and adaptation - on future work in order to get feedback on next steps. On top of that, the overall feeling was that ‘improvements are for Scrum Masters’ (one team member said that literally), so teams didn’t take responsibility to improve the way they worked and collaborated. The Scrum Masters didn’t organize an Overall Retrospective in over 6 months! At the start, the Product Owner and supporting Product Marketing people took responsibility from teams, by acting as both the domain experts and customers, which prevented teams from figuring out the customers’ problems and reinforced the previous behavior by teams: please tell us what to do. These factors are not helping to set the stage for teams to learn to self-manage.

The Scrum Masters were really diligent to help and move things forward. However, this led to compensating behavior, filling in gaps that appeared and helping to ‘push’ things forward to deliver features and fix problems. However, teams didn’t learn to self-manage this way, and didn’t take responsibility for these ‘gaps’ and kept relying on others, now on Scrum Masters instead of project managers. After a while with external help, Scrum Masters refocused and improved the basics of Scrum and LeSS to improve empiricism. One example was the improvement of Product Backlog Refinement (PBR), and helping teams how to do PBR, split big pieces of work in a good way and making sure that teams were the ones to make PBR useful, taking initiative and inviting users and stakeholders.

1.3.4 Inspection OD-element: LeSS Rule: The majority of the teams are customer-focused feature teams.

In the team self-design at the start of the LeSS adoption, one of the criteria was ‘being able to deliver as much of PBI’s independently as possible’. This led to teams trying to involve as many different specialties as possible within their team, instead of focusing on a specific - customer focused - part of the product. Some teams started learning from each other to increase knowledge within their team, e.g. testers learning to code and developers learning developing on more components. Other teams still had focus within their team on their old specialties, which led to a lot of handovers in the team, bottlenecks when wanting to work on certain features and limited ‘challenging’ and trying to understand the features at hand and the problems to solve. Consequence was that some teams started working on the ‘newer’ technologies for features, while other teams kept working on features that they ‘know’. This resulted in teams working on lower priority PBI’s, because those teams didn’t feel confident to work on the ‘newer’ technologies. Obviously, this didn’t help to adapt to work on the highest customer value.

This is a good example of the False Dichotomy thinking mistake sometimes made when adopting LeSS: incorrectly going from the extreme of a person and team knowing only one thing, to the other extreme of aiming for teams to know “everything.” The degree to which customer-area focus is important when starting to form the new teams is influenced by the difficulty in learning; in some smaller and simpler product groups this is not a concern. Although we had not adopted LeSS Huge at this point, note that this is the motivation for LeSS Huge: focusing teams within a smaller scope so that the learning required is not overwhelming.

1.3.5 Inspection OD-element: LeSS rule: The definition of product should be as broad and end-user/customer centric as is practical. Over time, the definition of product might expand. Broader definitions are preferred.

The broad product definition brought initial challenges for teams to have whole product focus and understanding. This was combined with eliminating most of the ‘undone’ work and bring it to the teams, for which the challenges explained in the following section.

For the other parts of the organization, the broad product definition was also a shift. Before, they had to connect to multiple teams to get things done. While now, they had to contact a single Product Owner and work with multiple teams during Product Backlog Refinement. Overall, this went quite well, though there were some challenges in people approaching developers that they knew well directly instead of bringing ideas to the single Product Owner.

1.3.6 Inspection OD-element: LeSS experiment: Try…Eliminating the ‘Undone’ unit by eliminating ‘Undone’ work

Before the LeSS adoption, there had been a component focus and many activities were scattered across the organization. Examples are the execution of regression tests, fixing bugs, other support (all spread across many component teams) and testing & releasing the product (separated team). From the start of the LeSS adoption, teams shared these activities. For example support duty and releasing the product were done by teams on turns (‘duty’), reflecting the LeSS suggestion of rotating any required focussed task (eg. handling release, surprise defects, improving the build system) across the feature teams. Teams found out that their build system and their own practices didn’t support them to be able to integrate easily and deploy their work. The build pipeline was not optimized for the whole product and consisted of many different branches, not a clear master branch, and no easy way to integrate into the master. Before, teams didn’t have the mindset to integrate their changes quickly, and created many different branches without merging to the master branch and removing obsolete branches. There was a lot of confusion on which branches to use and integration took a lot of time and effort. LeSS guide Integrate Continuously explains clearly that Continuous Integration (CI) is developer behavior. And to support this behavior the policies and tools should help, but the developer behavior and habits are still the main part of being able to integrate continuously. Executing regression tests and fixing bugs were - mostly, except for high urgency bugs - done by (automated) selection and if needed discussed in Sprint Planning 1.

Because the ‘undone’ work was the responsibility of the teams, the teams took more responsibility for these ‘pains’ and created more understanding of broader product matters by teams. Teams could do more - often small - improvements in how these things were done. For example when they develop a new feature, often they created automated tests as well, which made regression testing easier, faster and better. Before, the pains led to delays in delivery and quality problems in the product, which is significantly better now all teams (can) take responsibility for them. Though these pains aren’t completely gone - even not after 2 years in the adoption -, the teams reduced the pains significantly and it at least didn’t block the delivery of value. Most ‘pain’ right now is for teams having these ‘duties’ and working on these pains instead of developing (customer) features. Slowly, this is improving as well, but the biggest pains are at least conquered. Note that ‘pain’ as described here is the work that has to be done for teams, but the removal of many of the ‘undone’ work made the pain for the product significantly less, as a consequence of the OD change.

1.3.7 Inspection OD-element: LeSS experiment: Avoid…Functional units

There were several functional units prior to the LeSS adoption, which will be inspected in this section. In the team self-design, the Head of Product identified three types of specific roles that could either join teams, or stay outside of teams (use volunteering):

- Security specialists

- Architects

- User Interface (UI)/User eXperience (UX) specialists

From the start of the LeSS adoption, the security specialists decided to join (different) teams and spread security knowledge across teams, being ‘regular’ developers. They set up a strong community, invited all teams to send a representative (‘security champion’) to the community, to share knowledge and make sure each team knows the basics of security. The Head of Product and teams considered this approach successful and all teams were able to address at least the basic needs in regular development on security. Teams brought more complex matters to the community or they moved it to teams with security specialists. Teams felt more sense of urgency on security, which was a great result from spreading this knowledge across teams.

The architects decided not to join teams and stayed a separated group at that time. Following the LeSS adoption principle Use Volunteering, there was job safety for them (but not role safety). The agreement was that they couldn’t be blocking any developments and if they wanted to have influence on the product, they needed to work closely together with teams. Some of the architects did this quite well, and some architects didn’t like to work this way and eventually left. A few of the architects joined teams along the way, and from the next significant OD change (see upcoming section) they formally became part of a team. Their knowledge in teams helped teams to better understand the product, and the architects got closer to the actual product. This way they had much more impact, because they spread their knowledge more across the organization.

The UI/UX specialists decided not to join teams. In a later stage, they experimented to join teams, but teams and the UI/UX specialists didn’t consider it a success. In the experiment, they were working ‘in’ a team, but basically doing their own work and not getting involved in the teams much. For them, there wasn’t much overlap with the work of the teams, and teams saw no benefit in having them in the team, because they were mostly working on non-product related work. This was the general conclusion, and they moved to other parts of the company where they could use their skills. In the meantime, some teams had hired ‘frontend developers’, who were hands-on and joined development in teams. Their role was useful for teams and helped them in addressing ‘frontend’ work better.

The Product Owner was the manager of the product marketing group, organizationally located within Marketing, outside R&D. Most members of the product marketing group worked closely with the teams, similar to the PO representative or Supporting PO from the LeSS experiments (Practices for Scaling Lean and Agile Development). The PO representatives organized themselves mainly around ‘topics’, often customer centric features but also e.g. around requests or bugs from specific vendors. The PO representatives took their main role in Product Backlog Refinement, but also had an active role in Sprint Planning and Sprint Review. They discussed together with teams the importance of features and helped in making trade-offs. However, they still acted as a separate functional unit and while the collaboration had improved, teams weren’t able to do the work related to product marketing themselves and always needed to work with them to get things shipped.

The group of Scrum Masters worked within R&D, but acted as a functional unit. They were very diligent and were closely collaborating together. A downside of that was that they were too focused on the group of Scrum Masters and less focused on other important aspects from the Scrum Master role, especially supporting the Product Owner. Their main focus to teams was to organize and facilitate team- and multi-team events. We did a system modeling session with the Scrum Master group to understand the system and the main challenges. This led them to understand that they should address certain challenges where they were not focusing on. It was a start for them to understand the system better, understanding which challenges to address and how to make these things transparent. Very soon the group started taking the approach to make topics that they wanted to address more transparent, especially around the product (mainly the Product Backlog). With some support, the group of Scrum Masters were soon focusing on the main challenges, instead of the smaller focus they had before and their own group.

Considering these functional units, the best improvements resulted from the functional specialists when joining the teams. The OD change to avoid (and thus remove) functional units leads to major improvements in adaptiveness, but has serious consequences in the organization.

1.3.8 Inspection OD-element: LeSS experiment: Try…Work redesign

When starting the LeSS adoption, the work was redesigned to cover customer-centric Product Backlog Items, combining tasks (of different components and functions) in the feature teams. The teams struggled with this in the beginning - coming from component teams - because they weren’t used to seeing the whole product and the customer perspective. Working more closely with vendors, large customers and internal stakeholders that work directly with customers and vendors led to better understanding of the customer domain, and less ‘whispering game’. Before, teams received their work mainly from project managers or internal stakeholders, with almost no interaction to real customers and users. Starting defining customer-centric PBI’s required learning from the teams, especially in the area of refinement and work design. Over time, the teams got better at this and the OD change to redesign the work led to this improvement eventually.

1.4 Adapt

A summary of the main adaptations that happened in this experiment:

- A single Product Backlog with a single Product Owner

- Cross-functional and cross-component teams with shared responsibility for the whole product

- Teams shared the common work for the whole product (support duty, fixing bugs, regression testing & releasing) instead of having separate ‘undone’ units or teams

- Teams to self-manage (and improve in this area)

This brought the following main results:

- More emphasis on technical excellence

- After a while, better focus on whole product releasing

- Define Product Backlog Items more customer-centric combining component and function tasks in the end-to-end Product Backlog Items

- Teams being able to pick up more customer-centric Product Backlog Items and work together with other teams to learn when needed

After the re-alignment workshop, the Head of Product decided to add external - more intensive - help in their LeSS adoption, mainly focused on the mentoring of their Scrum Masters. This way, the Scrum Masters could learn and be able to move things forward by themselves. This is when the main author came in.

Based on the inspection, after a year Y Soft wanted to make the next big step forward. This next step involved a team redesign, removing the managers within R&D and the Scrum Masters role becoming the agile coach role and getting other people onboard with more experience in organizational design and team coaching. Y Soft CEO and Head of Product had several reasons for making the next step:

- Extend self-management of the teams, remove delays in decision making and increase organizational level transparency. The CEO decided to remove the management layer between the Head of Product and the teams, to get more transparency on things that happen within teams on organizational level and less people required for decision making (to get rid of delays in decision making) by removing the management layer.

- The amount of people (& teams) in the product has grown and the teams differ greatly in size. Teams hired new people and incorporated other roles (e.g. architects). The Head of Product added a full ‘team’ to the product from the infrastructure department (still as a component team), from which the skills needed to be divided between the teams. Additionally, the CEO and the Head of Product had the desire to add extra teams (capacity), so two new teams (fully hired from a consultancy company) started.

- Both teams and management wanted to improve the ability of teams to deliver end-to-end customer centric features better. This would result in more cross-functionality in the teams and teams being able to work on more parts of the product. Some teams realized that they needed to improve their range of skills to be able to deliver end-to-end customer centric features better. Some of these teams had a too wide range of specialist skills, and they needed some customer-area focus to be able to easily get better and learn within a certain focus. And not necessarily focus on being able to work on everything in the Product Backlog. These teams wanted to change team designs to optimize this. This resulted in top-down and bottom-up (for most people) support for the step forward.

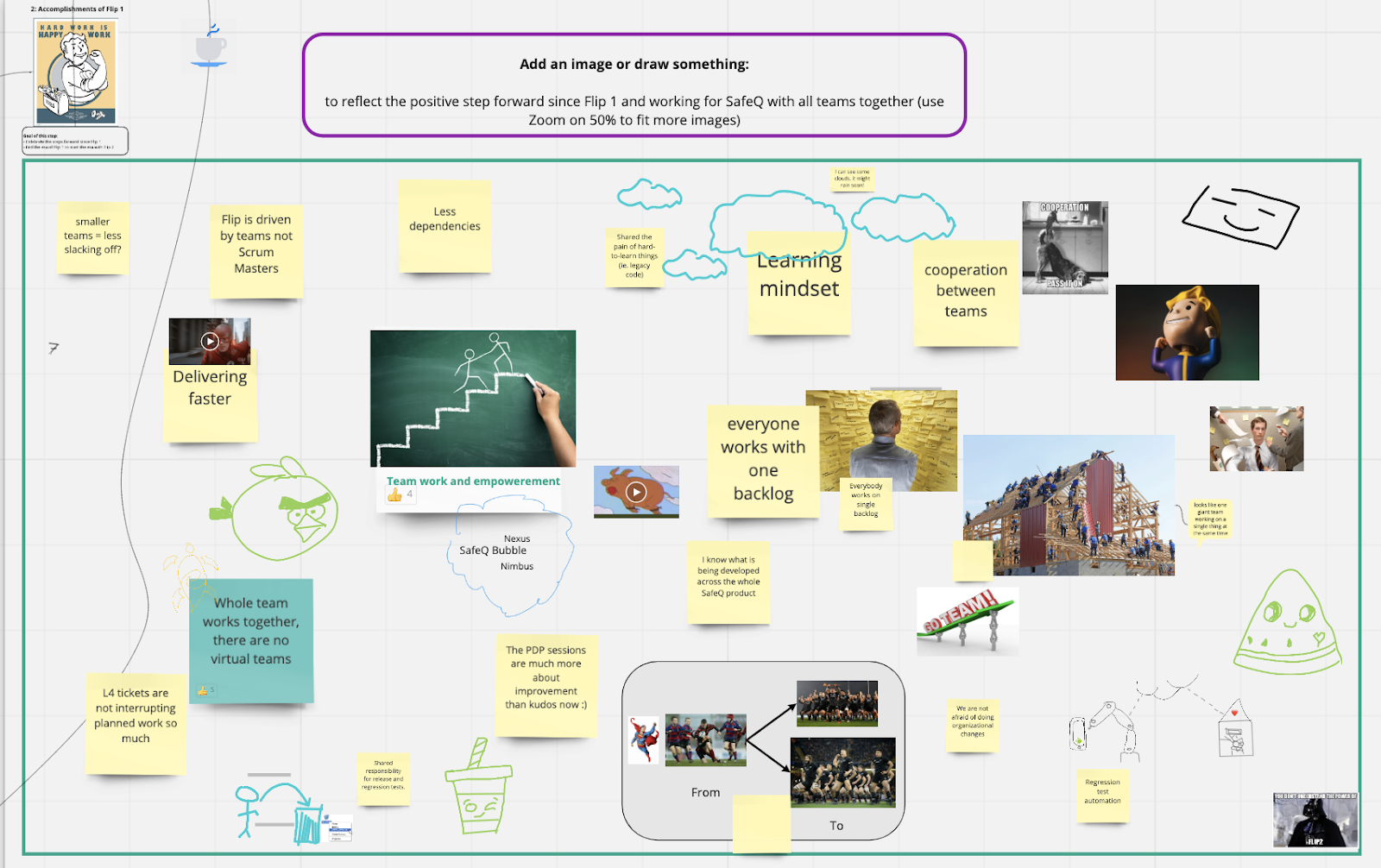

The next step was a second event that made significant Organizational Design changes and next steps in their LeSS adoption. They called this ‘Flip 2’, after calling the initial 4-day event that started the LeSS adoption ‘LeSS Flip-forward’ or ‘Flip 1’. Basically, certain steps of the LeSS guide Getting Started were repeated. A summary of the OD changes:

- Team (self-)redesign

- No more managers directly for the teams

The context and narrative for these OD changes are described in the next section.

2. Experiment 2 Organizational Design: redesigning the Feature Teams and removing the management layer

2.1 Context

As mentioned in the previous section, a new event was set forward to start the next OD changes. The event was planned on May 11th, already in February of 2020, before the COVID-19 pandemic arrived. The Head of Product decided to still move on, because 1) it was not clear when it would have been possible in real-life and 2) they didn’t want to postpone the further improvements and steps forward.

The main changes that happened were:

- Team redesign: people self-designed into ‘new’ team designs. The teams optimized themselves to ‘deliver more end-to-end customer value’. Additionally, the remaining architects and the infrastructure team people joined the teams.

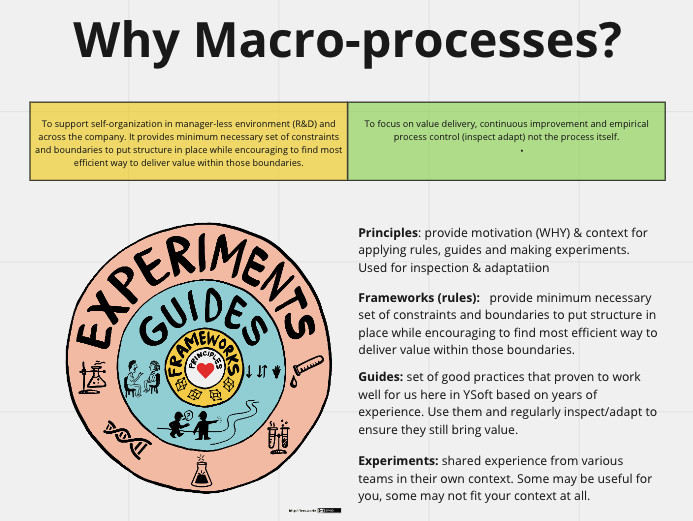

- No more managers directly for the teams: managers became either agile coach or left Y Soft. Teams designed ‘macro-processes’ to define how e.g. hiring, performance evaluation, and escalations will be handled without managers.

- Scrum Master role replaced for agile coach: the Head of Product concluded that the Scrum Masters had a narrow scope of attention (mainly on teams) and too little focus on the larger system and organization. Additionally, some teams had negative experiences with some Scrum Masters, for the same reason. That’s why the Head of Product decided to start working with agile coaches that had explicitly more emphasis on a broader scope of attention. Some Scrum Masters became agile coach, most Scrum Masters left Y Soft. In the upcoming sections, there will be a reflection about this situation and reasoning.

In the next section, the narrative of these changes and the reasoning behind these changes are described.

2.2 Narrative

In the second round of OD changes, certain steps of the LeSS guide Getting Started were repeated and improved. There were a couple of reasons for Y Soft to do these OD changes, which are listed below.

- Extend self-management of the teams and remove the managers

The CEO and Head of Product concluded that the managers limited the self-managing capabilities of the teams, caused delay in decision making and filtered information towards them. The role of the managers had already changed since the start of the LeSS adoption, where they were structured to ‘manage’ two cross-functional teams instead of their component or functional responsibility. The managers didn’t have responsibility for the results of the team. They mainly needed to deal with HR practices. However, the different managers filled in their roles in different ways. Some managers took a proactive role in escalations, negotiating between ‘stakeholder requests’ and the work of the team. While other managers focused on supporting the individual team members and stayed away from any influence on the team’s daily work. Some of this behavior led to dysfunctions and less self-management from teams. When the managers were removed, there was no drop in “predictability” and output of teams. Historically, the managers in R&D were an interface and escalation point for the rest of the organization. Removing this role without having clear ways to do support, releases, prioritization, working together between teams and the rest of the organization, would have been harmful. At the time it happened, it was possible because of the pre-conditions just described. - Functional teams added to the LeSS adoption and many new people joined the teams

There were several causes for changing within the teams: teams hired new people, people from other departments that joined teams, architects that - informally - joined teams, and people leaving led to differences in team size. Additionally, the Head of Product added the Infrastructure team to the LeSS adoption, but still in their original setup as a component team. They wanted to become more cross-functional and other teams wanted to have more skills related to infrastructure. - Desire to improve the ability of teams to deliver end-to-end customer value better