This post is cross-posted from the Gosei page at their blog

There are two very different strategies in adopting Agile in a large organisation, horizontal or vertical. In other words, you may take one product first with narrow and deep focus. Or you may focus on the vertical coordination layer, which is often perceived as The Scaling Problem.

First we look into the fascinating world of control, power and culture at different layers of a large organisation. Based on this analysis we draw our conclusions about the transformative power of LeSS and SAFe.

Professor William G. Ouchi is known for his book “Theory Z: How American Business Can Meet the Japanese Challenge”. It introducing the principles of Japanese management to Western business audiences and stayed at US bestseller list for 15 weeks.

Ouchi also studied mechanisms of controlling work in large organisations. He focused on two simple questions:

He identified three different mechanisms by which the control was achieved: Market, Clan, and Bureaucracy.

In real life these co-exist, but typically one dominates.

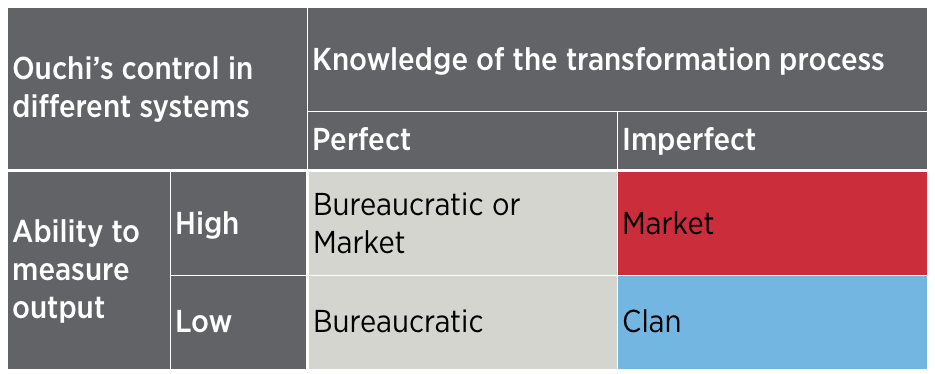

Different ways to control the work evolve based on two factors: First, are we able to measure the output, and second how well we can describe the transformation process of the work, from input to output. The following matrix classifies the conditions for the different types of control:

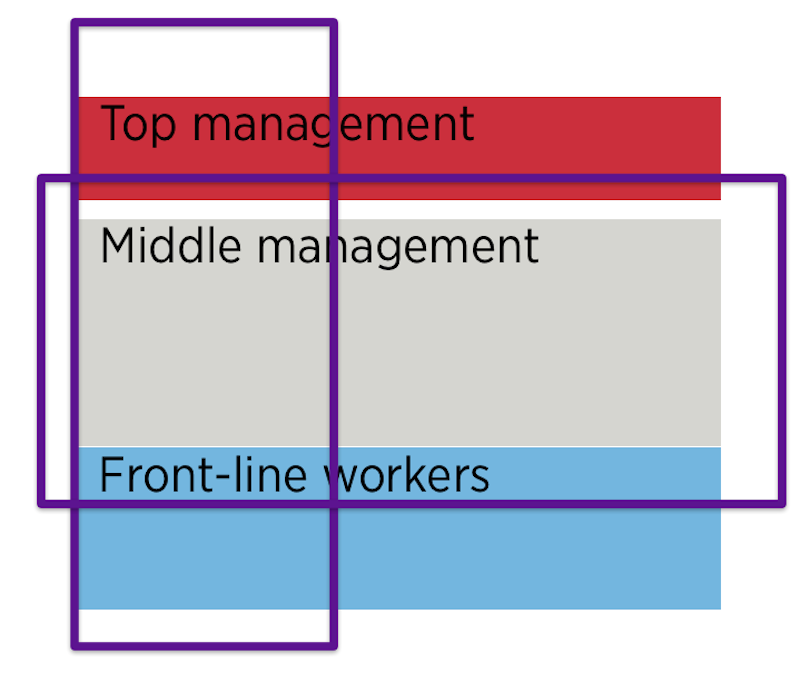

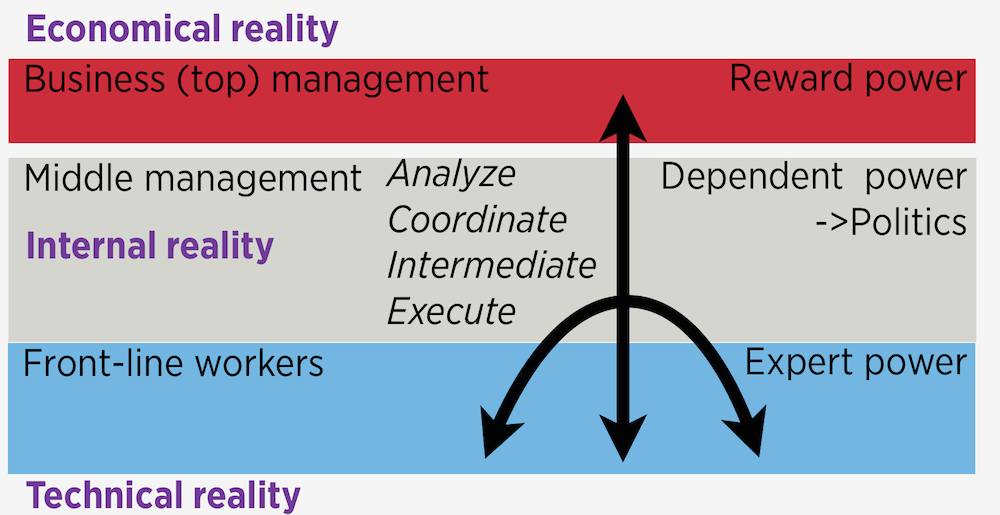

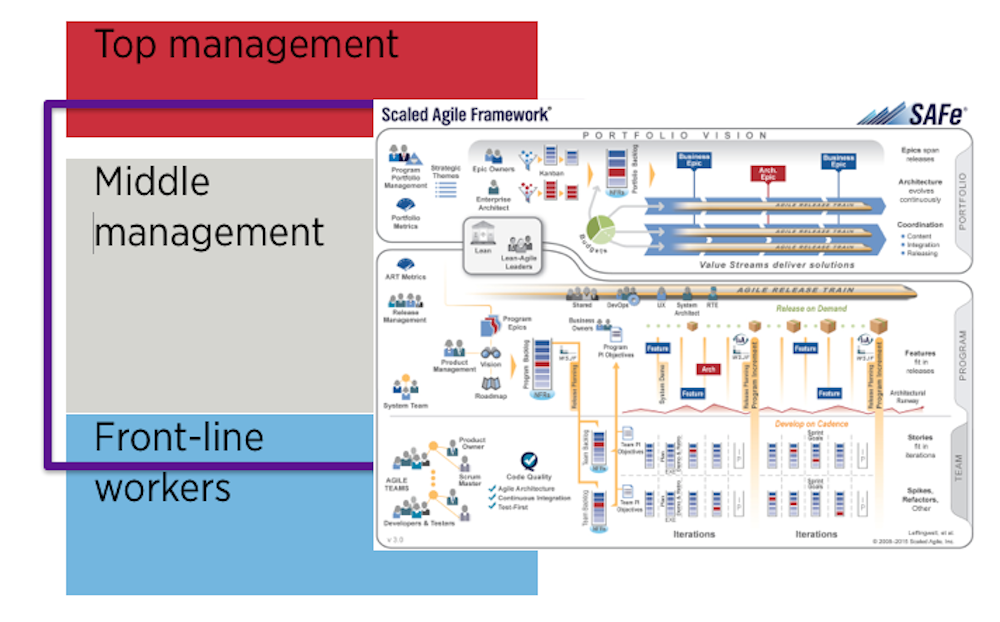

Let’s look at a typical large product development organisation. It may be for example the internal product development of a bank, or a commercial telecom infrastructure provider. The top management is in contact with the owners and market realities. At the bottom there are the front-line workers, in direct contact with the technical realities. The middle layer is mostly dealing with internal questions of control, coordination, intermediation, analysis and execution.

Top management is in direct contact with the capital market and business market. They have real profit and loss responsibility for the whole company or a business unit. They make decisions on behalf of the whole: where to invest money, if a product is started or cancelled, or people hired or laid off. They have power over resources, which is called reward power.

Market control is the dominant mechanism here. It is about money. You can look it as investment game; where to get the biggest return for my money. I don’t need to know how things happen inside the organisation, but the input (money) and output (what it I get with my investment) are measured.

Market control is not feasible when an exact contract can not be made or the parties involved can not measure profit and loss. Market control also requires competition that creates an incentive for both parties to do their best, and makes sure work is done using on fair price.

Front-line workers create the product. They work with technical realities. They have expert power – decide how to solve technical problems. Clan control is the only control mechanism that functions well when the work performed is unique, interdependent or ambiguous like software development.

Clan control is based on informal shared values and rules, traditions and beliefs. It works when the goals of the individuals and the organisation are aligned, and there is a high level of trust. Building Clan control is hard since the controlling rules are mainly informal and value based. It requires thoughtful hiring. Also, people need a long period of socialisation in order to become members of the clan.

Clan control may work at any levels of the company, but is mostly observed amongst front-line workers and teams. When the problems require, Clan control enables the most economical collaboration between front-line workers. There is no hierarchy or predefined bureaucracy that needs to be taken into account.

When observed from outside, Clan control seems to have no control. New managers often try to control the front-line workers by establishing more bureaucracy or market control. It makes Clan control hard to achieve, because other control mechanisms easily dominate.

E.g. The top management hires professional coordinators (project/program management) and gives them hierarchical authority to manage and evaluate front-line workers i.e. installs Bureaucratic control. Or the top management establishes Market control by adding evaluation and reward practices where the front-line workers compete against each other to get the rewards. These control mechanism instantiated by top management fail to work, because software development is inherently complex, unique, ambiguous and interdependent. Front-line workers in software development painfully experience and recognise this mismatch. It causes constant conflicts and frustrations between front-line workers and middle management.

The middle management works with the internal realities, possibly many handovers away from any external realities. They transmit the business contract to the front-line workers. They coordinate between different teams or individuals. They do all kind of analysis, plans and work supervision for the whole system. The legendary researcher Nonaka, the grandfather of Scrum, said that good project managers, who translate between the business and workers are essential for the successful Japanese companies (a few decades ago).

The top management has delegated some power to the middle management. The front-line workers have given some power over their doings to the middle management. So the power of the middle management depends on top and bottom. When there are many middle managers, they are also dependent on each other. They need to negotiate, which is called politics. The more middle managers, the more different roles, the more difficult politics. The level of complexity in this mess is reduced by agreed rules, responsibilities, processes and authorisations – bureaucracy.

The Bureaucratic control identified by Ouchi is based on rules, policies, a hierarchy of authority, written documentation, standardisation, etc. To make a bureaucratic organisation work managers need authority to maintain control over the organisation. One example of this control is the employment contract, where employees give power to managers to direct and evaluate their work. Employees trust that management will do a fair job in evaluation.

The German sociologist Max Weber argued that bureaucracy constitutes the most efficient and rational way in which one can organise human activity. Systematic processes and organised hierarchies were necessary to maintain order, maximise efficiency, and eliminate favouritism and other misuse of power. But Weber also saw unfettered bureaucracy as a threat to individual freedom, in which an increase in the bureaucratisation of human life can trap individuals in an “iron cage” of rule-based, rational control. – Wikipedia/Bureaucracy.

“What is not often understood is that bureaucracy developed as a reaction against the personal subjugation and cruelty, as well as the capricious and subjective judgments, of earlier administrative systems (such as monarchies and dictatorships) in which the lives and fortunes of all were completely dependent on the whims of a despot whose only law was his own wish.” – Evolution of Management Thought, 6th edition.

Bureaucratic control breaks when the work process is ambiguous, invisible, unpredictable. It also breaks when managers can not fairly evaluate the employees. Both of these happen easily in software development. The management often responds to these failures with more bureaucracy, which is part of the scaling problem.

The control mechanism type evolves from the system conditions, based on what is possible, and what is economical. Ouchi compares the control mechanisms with fish living in different kind of environments. Market control is a salmon, and Clan control a trout. They survive only in clear oxygen-rich water. Bureaucracy is like a catfish. It survives everywhere, also in muddy waters. It is the winner, as long as the organisation stays alive.

The fundamental mechanism of power, as recognised by Ralph Stacey, is “Power constrains the enabling conversation in organisations.” You enable desired patterns by releasing constraints and dampen undesired by adding constraints. You direct by lowering constraints in the desired direction. From this follows that it requires skill to use power with minimal friction and loss of energy. Bureaucracy is very effective in creating constraints. The more fragmented organisation, the more (conflicting) rules, the more friction – waste.

One-team Scrum beautifully creates the minimal bureaucracy, that enables the Market control and Clan control to be in dialogue. There are some rules but no middle manager roles.

The product owner can make a bounded risk investment. The input is measured accurately. Referring to Ouchi’s definition of Market control, the Product Owner can evaluate the result after an iteration. The Product Owner herself is evaluated based on her achievements using Market control. The team has conditions, which enable Clan control, for example a clear goal, immediate feedback, autonomy over it’s own ways of working, and empowerment to act on emerging impediments.

How to scale this to large organisations?

We have now analysed the layers of a typical large organisation and compared it with the elegance of Scrum. Next we look how LeSS and SAFe deal with the layers in large organisations.

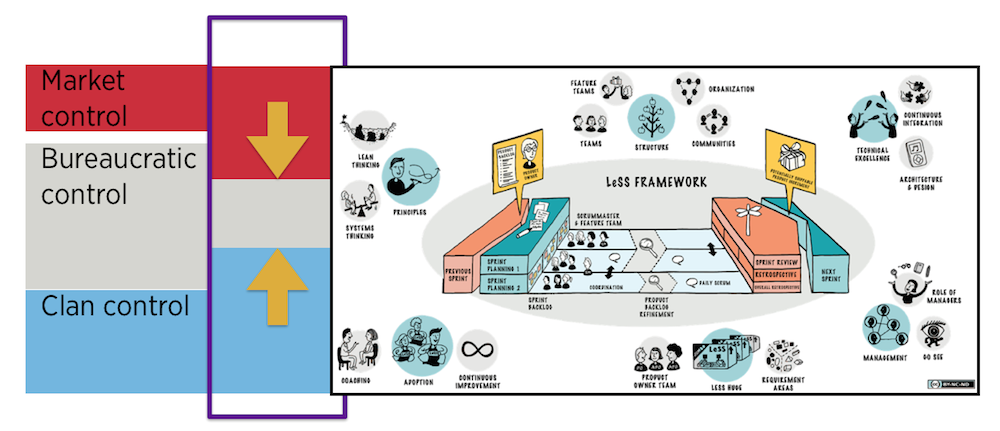

LeSS has Scrum in the center. It provides a set of principles, rules, guides and 600 experiments that help to change the surrounding organisation so, that Scrum scales up to a whole organisation. From the control perspective, this means minimising Bureaucratic control and getting Market control and Clan control into a close dialog.

LeSS adoption aims to remove the coordinating and intermediating middle management roles. The teams need to have as direct contact as possible with the business and with the customers. There is no program (coordination layer) – the empowered real Product Owner decides, and Teams with direct customer interaction clarifies needs. This reduces the work for the bureaucratic layer dramatically. What to do with the coordinators and managers? They will learn new things, move into teams, move to product management to work with the customer, or take a coaching role. There is job security, but no role security.

Reducing Bureaucratic control is only possible when the whole organisation from the real business to teams is changing together. LeSS has narrow and deep focus to ensure enough support for the organisation changing, to limit the risk, and to have a real working example for the neighbouring products after the first success.

The SAFe big picture fits perfectly to the typical structure of an existing large organisation. It introduces a new coordination process for the middle layer. The top layer of SAFe big picture is portfolio coordination, high-level queue management. Scrum, which is at it’s best in creating the dialogue between Clan and Market control, can be seen at the bottom.

SAFe removes projects that control individuals’ time, but is liberal in having old and new coordination roles in the middle management. This means that the proportion of the bureaucratic control is not reducing significantly. This is logical because of systemic conditions remain the same, or change slowly. When the need for coordination stays, the coordination stays.

SAFe actually takes granted that you need the various middle management roles. “We need to have people in roles (it doesn’t matter what their titles are) that can take a large initiative, break it into smaller initiatives, manage the small initiatives, and deliver them. You have to have that.” – http://www.ugilic.dk/blog/2017/04/interview-with-dean-leffingwell-about-safe/

To support the process, SAFe provides a wide set of Lean-Agile best practises to improve the ways of working. Good consultation often helps to get results, also with SAFe. However, there is the risk that the systemic conditions are not changing, and the change remains superficial.

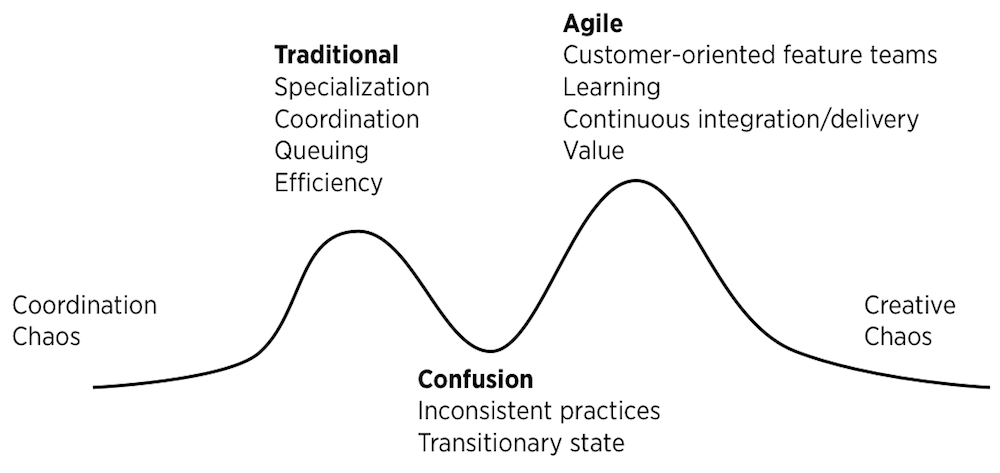

SAFe and LeSS target into two different local optimums, each having a consistent set of practises, structures, skills, technology and culture. This has an analogy to species in nature. Grass-eaters and predators have different combinations of characteristics.

SAFe is not aiming to reduce the Bureaucratic control enough to move the organisation away from the Traditional optimum. Instead, it tries to optimise the existing organisation by creating Lean-Agile programs. The project/program management is an old mainstream practise at this optimum.

LeSS aims to reduce significantly the Bureaucratic control. It provides a mutually consistent set of practises that move the large organisation to a new Agile-optimum. In next blogs we will write more about the characteristics of the two optimums.

Some references and further reading on topics covered in this blog post: