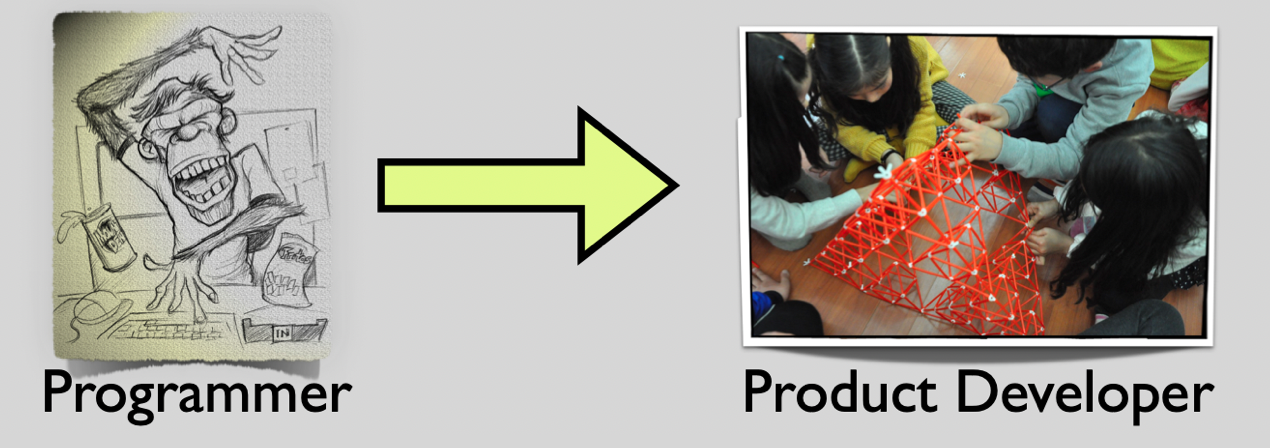

The Rise Of The Product Developers - Part II, Critical Thinking

In the first part of the Rise of Product Developers series, we explored how Product Developers focus on the domain and users’ problems to build a product. The true value developers bring lies in their critical assessment of what and how they’re building. This approach has always been essential, but...

.jpeg?preferred_lang=fr) by

by