Port of Rotterdam

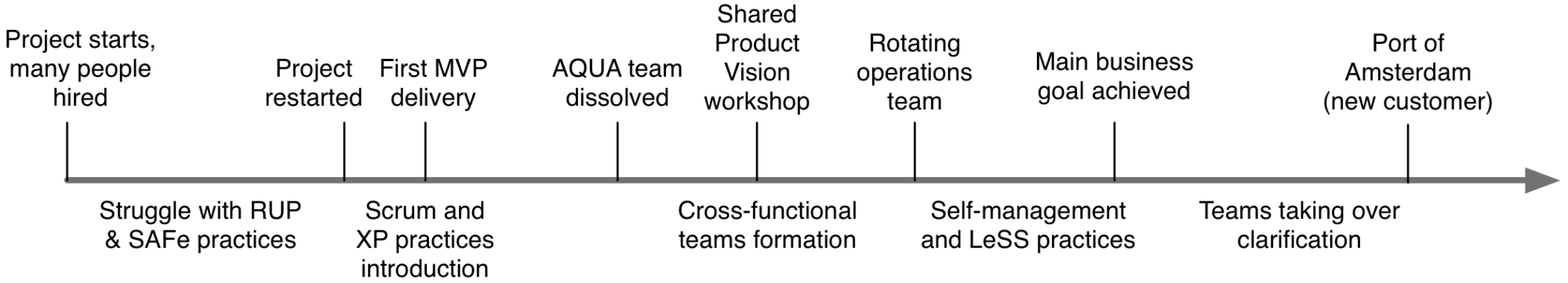

Port of Rotterdam HaMIS Development: a LeSS Perspective

This is a comparison of a Port of Rotterdam case with LeSS principles and organizational design. It is a story about four cross-functional feature teams (that also did operations; i.e., DevOps) delivering and managing a business-critical 24/7 harbour management product used by vessel-traffic services operators and several other types of users.

Context & Customer

The Port of Rotterdam Authority has a turnover of approximately €600 million and a staff of 1,100 employees with widely varying commercial, nautical, and infrastructure-related responsibilities. The foremost customer for the feature teams is the Harbour Master division. This business unit ensures the smooth, clean, and secure handling of shipping traffic (annually, approximately 33,000 ocean-going and 110,000 inland vessels).

The users are diverse. Some work for the Harbour Master division, some for other divisions, and some for the many partners of the Port of Rotterdam.

At the center of the primary business processes sits a product called HaMIS (Harbour Management Information System). The idea for HaMIS was born many years ago with a need to replace an existing one. The previous system had served well the Port of Rotterdam for 20 years but the old technology and architecture had become a major obstacle to any significant improvement in business processes. The Port of Rotterdam was growing and changing and the old system could no longer meet requirements.

The first goal was simple: minimize the negative impact of an outdated system. The secondary goal, on other hand, was a bit less clear. The Port of Rotterdam is growing, especially with the Maasvlakte 2 expansion. The product must support ever-growing traffic in the harbour with the same amount of people. This implies intensified information exchange, better coordination between involved parties, and better support of main Harbour Master processes.

How it all Began

The start of a complex process of making plans, budgeting, involving vendors and software integrators, and a dreadful procurement process followed the decision to replace the old system with HaMIS. This was suppose to be an outsourced development project. This process produced a lot of documents but no real code except for a proof of concept.

Eventually, the port made a courageous decision to bring the process to a full stop. The developing programme was too complex to ever be successful. The requirements were complex and the risk high. Too much remained unknown, and it would be big news in the Netherlands if the project failed. The consequences could be even worse if a faulty system would go into production.

But the existing system was approaching end of its life, so the Port of Rotterdam did not have any choice but to restart the project with one main goal for now: replace the current system with a new one providing at least the same capabilities. This time, Port chose to do internal product development over outsourcing to one or multiple system integrators.

The new product development’s chosen approach was a combination of RUP and fake Scrum (though of course, it wasn’t officially labelled “fake”). While 3 “Scrum” teams of just programmers were having stand-up meetings and starting to try other practices, there were also 8 different kinds of architects and analysts in a separate team called AQUA (architecture and quality assurance).

It seemed that the original intention was point kaizen. Within the assumed restrictions of existing organisation, the group would do “Scrum on development level”. The work was prepared by a group of analysts and architects.

From Scrum-But-But to Scrum-But

The RUP/Scrum-But-But combination was not really working. A coaching company was hired to help them learn how to change to Scrum. They provided Scrum trainings and hands-on coaching. But it wasn’t fully changed to Scrum yet. For example, the group decided to educate and appoint two people as the “Product Owner,” and in any event there was actually still a project and programme manager making the decisions.

Because Scrum had been incorrectly introduced as a practice for the teams rather than a change in the organizational design that impacted existing groups and manager roles, there was still an AQUA team, and the “Scrum” teams were not cross-functional, self-managing, nor were the people demonstrating multi-learning and multiple skills. And there was still a project manager responsible for “meeting the targets” rather than a real Product Owner. Also a number of SAFe practices, such as “architectural runway”, were discussed or introduced.

The coaching company introduced many team and technical level practices. For example, after a check-in (trunk-based integration using SVN), everything was built by a build server (Jenkins) in which Sonar was used for quality checks. The tests included unit tests, a handful of Fitnesse tests and record and playback tool for testing GUI. The last one was completely removed in a later stage. Also, the automated tests were not yet part of automated build at this stage.

Things were improving and something closer to Scrum and its results was emerging. Sprints were 3 weeks, and all Scrum meetings were practiced. More importantly, after each Sprint, a single potentially shippable product increment was delivered to a production-beta environment where some key users tried new features.

Improving from Scrum-But to Scrum

This is the moment I was hired to be architect and agile coach, and when the coaching company left.

Although they called me agile coach and architect, I was in reality intending to work as a Scrum Master to help introduce real Scrum into the organizational design. Each team had officially a Scrum Master, but in reality they were just team members that spent more time on facilitation than other team members.

LeSS rule: Scrum Masters are responsible for a well-working LeSS adoption. Their focus is towards the Teams, Product Owner, organization, and development practices. A Scrum Master does not focus on just one team but on the overall organizational system.

The first thing we did was dismantling of the AQUA team with the goal to have system kaizen. Dismantling happened by gradually moving decision making to feature teams. Also, the remaining AQUA team members were not clinging to this old groups. Nevertheless, some of them did want to keep their authority over analytical, architectural, and quality assurance areas despite elimination of the AQUA team.

By the end, there was nothing left to do in that team. In other words, real Scrum feature teams that do everything end-to-end had been successfully established. And there was not anyone in between the feature teams and users. The AQUA team members either left, became part of feature teams, or were assigned to other tasks outside product development organisation.

The knowledge about requirements and architectural concerns, experience, new insights, and constant changes in business requirements all started to happen within the teams.

The challenging part of this transition was the AQUA team members’ specific titles and roles. These were removed completely after quite a lot of effort. The titles and roles, such as different analysts and architects, were twofold. Their official organisational title, given by their employer and HR has never explicitly changed. At the same time, these titles and roles became, after organisational change, meaningless in the perspective of HaMIS product development.

Occasionally, this created a minor problem when line organisation was trying to influence product development through the roles people had. An example is discussion about “transfer to operations once project is finished”. In reality, there was no real project anymore, but continuous product development and management. A slightly bigger challenge was when line management was trying (without succeeding) to assign tasks to people, despite the fact they were fully assigned to HaMIS product development. Also, there were several KPI’s which were linked through annual appraisals. A few team members did not get the full raise because they did not achieve their KPI’s.

The root cause of these problems was an ongoing matrix management structure, where people are officially reporting to their functional line manager AND the project manager. The organisational change has removed reporting to project manager, but reporting to functional line management still remained a bit in the background. The problem was limited to just a few people, and because of typical Dutch corporate culture and great overall results, they were able to simply ignore line management influence.

At this point in time, we still had an active project manager who was gradually learning to let go. He was still expressing what he wanted, rather than full control being in the hands of a true Product Owner.

One of the pseudo Product Owners started to behave as and was treated as a real Product Owner. Both of them came from The Harbour Master division (business). The real Product Owner was also the one who did prioritization and Product Backlog updates. He had enough authority to make product-related decisions. The second one was officially still called a “Product Owner”, but in reality wasn’t seen as one. Unfortunately, he continued to act as intermediary (a business analyst) between teams and users, increasing handoff, talking to people, and collecting feedback. This problem was never completely resolved, only reduced in time. The lesson I learned afterwards is the significant disadvantages of having pseudo Product Owners that are just analysts in between teams and users. This is something I (incorrectly) thought at first was an acceptable compromise, not foreseeing the complications it would cause

LeSS rule: There is one Product Owner and one Product Backlog for the complete shippable product.

During this phase, the real Product Owner was taking care of ordering the Product Backlog, and collaborating with teams by explaining items and providing answers to any questions. Unfortunately, he also continued to act as an intermediary between the teams and stakeholders sometimes, rather than connecting the teams and stakeholders directly. Another major weakness from the Product Owner was a lack of a clearly expressed vision and direction. The problem is eventually solved with a two-day Initial Product Backlog workshop, which is more extensively explained later-on.

LeSS rule: The Product Owner shouldn’t work alone on Product Backlog refinement; he is supported by the multiple Teams working directly with customers/users and other stakeholders.

In the first five months after this more meaningful organizational design change, the top items on the Product Backlog were not replacements of old features, but completely new features. The consequence of this was that the technical implications were fairly simple and the team could deliver quickly. Also, users were eager to start playing with something new of real value in HaMIS, something they didn’t have in the old system.

Before all this, while sinking in an overloaded RUP and SAFe boat, attention focused on delivering all kinds of documents and making too many speculative architectural decisions. In those first Sprints after the removal of RUP and the initiation of Scrum training, the focus had moved towards embedding the agile mindset. Everyone was talking about this thing called Scrum and how it works. Some were skeptical (e.g., about continuous experimentation), but most were eager to try and learn. Also, every aspect of the development life cycle had started to improve. Continuous integration, TDD, ATDD, pair programming, and other XP practices became gradually embedded. Some might say that despite the effort spent on learning, the teams were already delivering new features into production according to a unified Definition of Done, after every Sprint. But I would rather say that because of the effort spent on learning, the teams were delivering new features every Sprint!

And the check-out and check-in cycle time started to improve from once a day per (pair of) developer to about once every hour. In short, the group was starting to move towards real continuous integration (CI). Developers were continuously extending quality checks during the local build. Eventually, even a slightly-too-complex function would fail the build. The product was always ready for a release. It became a practice to bring a tasty cake for everyone, whenever someone was rushing things out without running these checks. This didn’t include breaking the build because of frequent integration. After some time, the build system became a multi-stage CI system with 3 stages driven mostly by automatic promotion and some parallel processing. Eventually, there was definitely a culture of behavior change by developers to integrating continuously (that is, real continuous integration) , and not just using a build server and incorrectly calling that “CI”.

LeSS

Because LeSS (Large-Scale Scrum) is a straightforward, simple, consistent extension of Scrum when working with multiple teams, it is probably common that various groups have re-created most or all of LeSS, even if unfamiliar with the existing LeSS books (by Larman and Vodde) published in 2008 and 2010. And that was our case when we first started this journey in 2010 (Scrum introduction at Port). So it is interesting to me to reflect on what we did, now that I have a full understanding of LeSS, to compare and contrast our case with standard LeSS.

So “basic LeSS” was starting to take a form, although we never mentioned the LeSS framework. The ways of working and practices were introduced based on previous experience, but even more as experiments. These were the most important principles in the beginning:

- Whole product focus with potentially shippable increment after every Sprint

- As close to the customer as possible

- Everyone should be involved in the whole product focus, remove any unnecessary roles and individual responsibilities

- Bring challenges to the teams, don’t try to solve them outside

There was definitely no need for the LeSS Huge framework. Before reorganisation, there were 3 component teams, 1 architecture / QA (AQUA) team, and 1 operations team. After reorganisation, we had 3 feature teams. Much later, this was extended to 4 feature teams, as explained further in this account.

LeSS Rule: The majority of the teams are customer-focused feature teams.

This reorganisation was followed by strong push for self-management. What this push meant is explained in further sections. The project managers gradually stopped their interference, they stopped making any decisions or giving any work and instead were just arranging budgets and communicating with the rest of organisation, which didn’t understand well enough how this Agile development was working. Idealy, this work should have been done by the Product Owner, but he lacked the influence that the project managers had. Although the change in attitude of project managers was slow, it was painless. The main reason was that one of the project managers was the first and main advocate for Scrum. He is now not a project manager anymore.

LeSS rule: In LeSS, managers are optional, but if managers do exist their role is likely to change. Their focus is the value-delivering capability of the product development system rather than the specific scope of a product.

The Product

The first version of product was already partially implemented before the Scrum introduction. The fundamental technical elements were use of Java, a standalone Java client written in Swing in combination with JIDE, an IBM WebSphere platform on the server side, and SOAP over HTTP as the protocol between client and server. There was even a SOA with an enterprise service bus. Design and layering of the backend was based on standard JEE patterns (service, business, data). A separate server-based solution with Erdas Apollo software delivered geospatial data to clients. Altogether, this was definitely not the simplest possible solution, it was over-designed. In fact, the front-end part was based on a proof of concept, which unfortunately was not thrown away. Nevertheless, with a few adjustments it was workable in the first Sprints.

Almost all of these original choices were changed significantly or removed in the following years, replaced with simpler solutions as the number of features and intrinsic complexity grew. The statement “We need to choose complex technology in order to anticipate complex requirements later on!” proved to have the opposite outcome. The chosen technologies were not needed, so other technologies replaced them along the way.

Similarly, the original overall design was put aside after the reorganisation into cross-functional feature teams. Focus has moved towards actual code and therefore an already-implemented design.

Architecture and design still had the teams’ full attention. The main driving forces in evolving the architecture were requested features, rather than speculation. This translated into following key design rules for the group:

- If it is not needed by business in this or the next Sprint, than it is not decided upon, designed, or built. It might be discussed, but only briefly.

- We must replace the old system as soon as possible.

The biggest challenge here was not the technology and knowledge of design techniques but getting clear information from domain experts and users. The complex subject matter meant that not many people could explain how things really worked outside in the real world.

Thinking in simple solutions was gradually embedded in the minds of everyone involved. This thinking manifested in continuously questioning and replacing already implemented choices and always choosing the simplest possible option while clarifying and estimating big and small items. An example was replacing the SOAP over HTTP interface between the client and server with Hessian binary protocol. This primarily meant removing a lot of code, which felt really good.

Nevertheless, before any of these technical discussions, teams demanded not only requirements behind items for the following Sprint but also a proper explanation of context, the business process behind items, and any requirement that might impact the choices at hand.

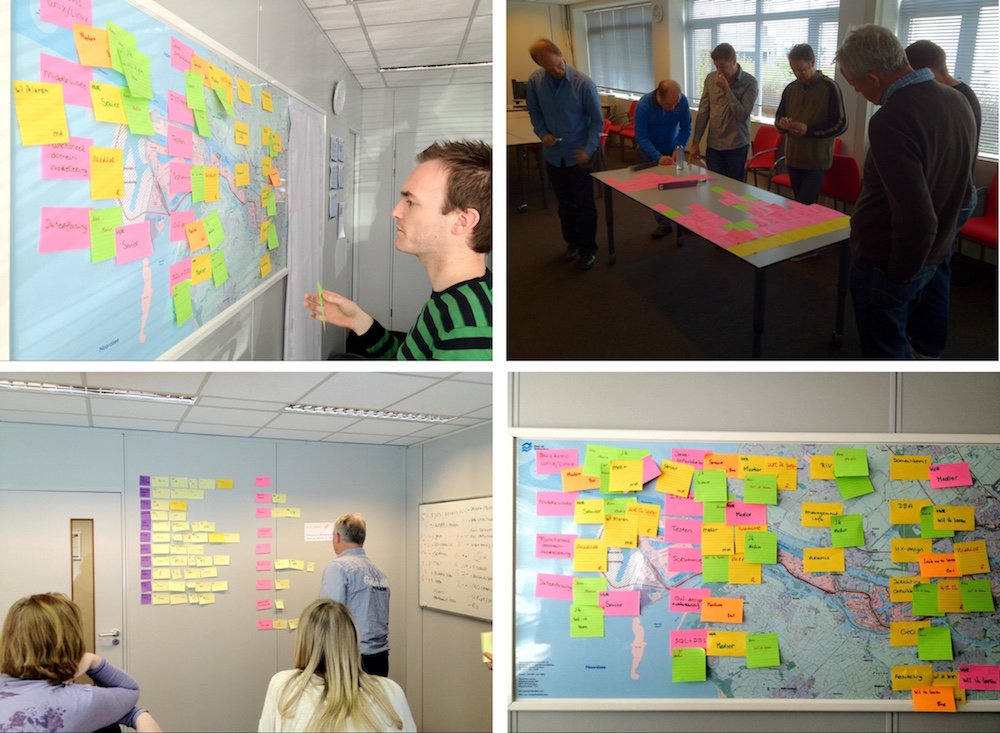

The teams were solving a problem, and therefore not merely delivering a solution. This was most visible during a whole day Product Vision Box workshop, where teams intensively engaged with Harbour Master and other business people to define a product vision.

The results of this workshop were a shared vision and high-level items for the Product Backlog for the coming 2 years. There were many more, different kinds of workshops after this one.

Instead of spending a lot of time on choosing a grand new technology to serve for the next 20 years, teams refocused on understanding which requirements would fulfil design or technology choices in the present. When requirements were currently lacking or much further in the future, teams would take these into consideration:

- Is the current choice going to prevent us from meeting those requirements in future,

- and will it be costly to replace this choice?

If no, it becomes a waste of time to further analyse the choice.

In other words, we spent huge amounts of time on understanding short-term and long-term business requirements but very little or no time on the design and architecture of things not used after following Sprint.

All significant decisions, decisions with larger impact, were taken during two kinds of cross-team design workshops:

- Triggered by a just-in-time need from any team, for the current or the next sprint

- Chosen from a wall with subjects, where everyone at any time could place any to be discussed subject.

Such sessions were timeboxed at one hour and usually followed diverge / converge setup. After one hour, teams either made a decision or concluded to do more research.

All design decisions were made by teams. In the beginning, the most experienced team members made these decisions. This caused problems in team dynamics. Design discussions resulted in decisions and whiteboard sketches. Since these drawings largely defined the tasks belonging to a story, the other team members felt disconnected from what was happening.

LeSS rule : Cross-team coordination is decided by the teams.

Eventually, design and architecture discussions became a team and cross-team effort. They usually started during the Sprint planning One, but the real work was done just before a team started to work on a specific item. When item required coordination with other teams, the dependency was resolved in a natural way by simply talking to each other directly. There was no cross-team coordination in any way outside the teams.

LeSS Guidance: Coordination via Open Space, joining other teams’ Daily Scrum, Scrum of Scrums, multi-team workshops, or “simply” working in the same space, talking to each other, and using visual management.

On a more detailed level, a Sprint may had one discussion for each item if needed. The rule of thumb was that a discussion ended when all team members understood the design and could participate in its implementation. The more experienced developers were still the most active during these sessions. Other team members usually asked questions, which the experienced developers answered. All teams were invited to participate in any decisions with big impact.

Every single aspect of architecture emerged gradually or changed. Everything was introduced only when needed, except for the planned, gradual replacement of many obsolete technologies. In the beginning, only one server instance provided services to clients, and the database and the domain model contained only those classes needed for the stories built at that moment. We had a walking skeleton with only one leg. It could jump and that was good enough at that moment. Once we realised it would probably fall because of additional weight, we introduced another leg, and a cluster was born.

In my experience, a complex architecture like this can definitely emerge as long as teams constantly spend a considerable amount of time on design and architecture through discussion and workshops.

A remarkable achievement was that teams were improving the overall quality, while intrinsic complexity of the product was growing. The quality was continuously monitored with Sonar and many related tools. At some point, an external company also performed an audit and graded this system as top 5% of all systems they have measured worldwide. The major driving force for high quality is a strong sense of craftsmanship in most team members.

Since teams, together with the Product Owner, were able to decide how to spend their time, they would often choose to experiment and build new innovations. We often held hackathons and ShipIt Days, during which we would try to deliver in one day something that was not yet on the Product Backlog, more or less free from any constraints.

Process

Focus on Users

We used many of the well-known practices for understanding business needs: user stories, epics, themes, and releases. Although they’d been useful, teams spent most effort on simply inviting users to visit or visiting users on the job, talking to them, and, most importantly, observing their work (“Me and My Shadow” - an innovation game). HaMIS team members would take the initiative, without Product Owner involvement, to arrange visits. As a result of this effort, epics and user stories were often rewritten or replaced. Teams would usually involve the Product Owner afterwards. While the Product Owner was generally absent during these sessions, he or she still decided whether or not items should be placed on the Product Backlog, and where in the Product Backlog.

LeSS rule: All prioritization goes through the Product Owner, but clarification is as much as possible directly between the Teams and customer/users and other stakeholders.

Users had become involved in the process, and were visiting teams on weekly basis. Sometimes, a whole team would take their laptops and work at place where users are for a few days. Certain features required a lot more feedback, and proximity makes collaboration more efficient.

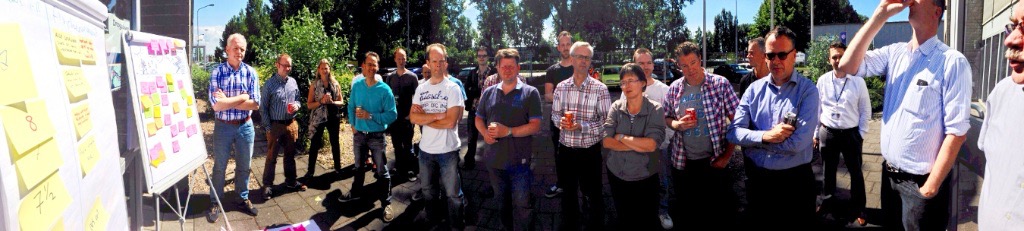

During Sprint Reviews (one in which every team demonstrated their features), where product increment was shown and feedback received, a meeting room would be completely filled with users and business people. Unfortunately, it gradually became more difficult to keep them coming after every Sprint. Continuously delivering new features for years became business as usual. In the beginning, everyone was excited by such fast delivery.

LeSS rule : There is one product Sprint Review; it is common for all teams. Ensure that enough stakeholders join to contribute the information needed for effective inspection and adaptation.

A big lesson learned was that comments from the Product Owner or someone similar could never replace talking to users. In complex challenges, collaboration with users became even more important. Occasionally, teams misunderstood the need, which resulted in rewritten functionality in the following Sprints. An interesting observation was that talking to users seemed occasionally difficult. Users really liked to talk when asked specific questions. They would expound on all kinds of detail at that moment, while we came for specific answers to specific questions. This was due to different perspectives between their world and our software world. Nevertheless, team members found that talking to real users was definitely the most effective and accurate way to discover requirements. Despite difficulties, it was always worth the effort and beneficial for all involved.

On other hand, requirements were often unclear or improperly justified, frequently due to a difference between how users were working with the old system and how harbour management wished to improve the existing process. The usual solution to this problem was to simply choose the most probable approach and show it to everyone. In other words, an experiment. Any changes as a result of this shortcut were still more cost-effective than further discussion or pushing the problem back to business. Probably the most important reason for why this worked is the trust higher management had in the Product Owner. Imagine the cost of four teams during one or more Sprints, and then duplicate costs in following Sprints as they must partially or completely replace functions.

A major mistake we made was that the Product Owner worked with so-called “subject-matter experts” or “domain experts” who were actually analysts that gathered information, met with people, and wrote requirements.

They created another queue with functionally analysed requests, with more WIP, handoff and information scatter wastes. This approach prevented teams from really understanding the problem and asking “why” questions. Not only did real understanding got lost in translation, but one of the first feedback loops became broken.

Eventually, we decided to apply one of the guides in LeSS: Hands-on development feature teams help the Product Owner more, doing most of the clarification work on items and talking directly with the users. So then the overall Product Owner could focus more on prioritization, while the teams focused on clarification.

Therefore, analysis and exploration of items shifted from analysts to the teams. The presumption that “nerds” were incapable of asking the right questions and should not talk to business proved to be completely wrong.

Just-in-time delivery improved

We have removed this queue (functionally analysed requests) completely and gradually reduced batch size. In the first 20 Sprints, a lot work is spent before an item was ready. Each team’s tendency was to reject an item if something was unclear. In the early phase (before the teams did most clarification) this pushed the PO and “domain experts” (really, just analysts) to keep spending time on “preparation”. Therefore, the PO would usually prepare items many Sprints in advance. At some point, the realisation came that this “preparation” makes things only worse. Lead time was long, premature preparation was essentially making feedback loop much longer or too late to give, and prepared information was not really useful after all. There was more of the wastes of overprocessing, WIP, and handoff.

This was first changed into much more meaningful and intensified Product Backlog refinement, where sometimes barely identified ideas were given by the Product Owner and then teams would define and split into or write fine-grained items.

In other words, teams took over the clarification of items. The teams did this clarifying more just-in-time. The items were prepared only one Sprint ahead. Also, teams became more comfortable with accepting relatively “unprepared” items and doing all analysis (also talking to users to clarify things on a detail level) during the Sprint. At some point, tasks were not defined during Sprint Planning part 2, but written just-in-time, when team decided to pick up the next item during a Sprint. The reason was the waste created by asking questions like: “Does anybody know what this task was about?”. They were simply created too early. The effect was reduction of tasks batch size.

Another thing team members did is to continuously ask each other during the Daily Scrum how to help finish an item they started working on, before picking up a new one. This action reduced WIP further to 2-3 items per team. Accepting the fact that sometimes team members didn’t have much to do, and would try to help others to finish an item first. Pair-work fitted perfectly in this practice.

More work, so more teams?

Our teams constantly improved, with great results. The rest of the organisation noticed. This had two effects:

- Other IT departments and teams started introducing Kanban or Scrum

- Business people with budgets made more and more requests, even from outside of Port of Rotterdam.

About 2 years ago, also the Port of Amsterdam wanted to replace their system with HaMIS. This did not mean they would receive a download with our software; our teams and the PO suddenly had a whole new group of stakeholders and users for the same product. The principles of incremental delivery and close contact with users and customers are still applied. The difference was that teams needed to spend some time in Amsterdam, too.

LeSS rule: The definition of product should be as broad and end-user/customer centric as is practical. Over time, the definition of product might increase. Broader definitions are preferred.

The Product Backlog contains work for multiple years. All these stakeholders wanted to have their value preferably yesterday. This automatically triggered the question about scaling towards more teams. More people means more work can be delivered, right? Every time the question would arise, the teams’ answer was “No!”

We realised that the request for more teams was by itself an incorrect request. The correlation between more teams and more production was, at best, weak. At worst, it could have exactly the opposite effect. The requests were followed by a number of questions from the teams:

- What is the exact need? Is it clear enough?

- Should this be part of HaMIS as a product?

The most important conclusion was that teams would rather keep improving effectiveness through better ways of working together, improving the organizational system, and especially with users and stakeholders, instead of introducing new teams or team members. Eventually, both teams and management agreed on this way of thinking. We all had a strong feeling that a lot can be improved in the system, even after four years. We came back to the observation that one of the most important areas of improvement was the Product Backlog. This was also the reason for the question above.

In the first three years, only three teams built HaMIS. Eventually, the teams themselves decided they could hire additional experienced craftsmen and craftswomen, create another team, and still be effective. A good thing about new team members is the experience they bring from other projects.

Organisation

Self-managed, cross-functional feature teams

It took a lot effort to give teams the authority to make decisions on their own. The challenge was not the teams, but the rest of organisation. Management and other involved people were accustomed to certain ways of working (“It is part of my responsibility as a manager to make these decisions”), which needed to be moved to teams. The main mantra, whenever someone from outside suggested to change something or make a decision, became: “Bring this subject to the teams!”.

This trust given by management to a whole team created sense of responsibility. It is the trust that teams were very much capable of making decisions with large impact. Management and PO also gradually stopped approaching individual team members for specific tasks or any kind of performance review or feedback.

LeSS rule: Each team is (1) self-managing, (2) cross-functional, (3) co-located, and (4) long-lived.

Team members identified mainly with a whole product and therefore all teams together, and secondly to their own team. Teams were fairly stable, although they decided to shuffle 3 times in 4 years for more fun, better knowledge sharing and getting to work more closely with other people too.

This shuffling was a self-designing teams session and was done in about 1-2 hours:

- Define all skills / disciplines a team should have with post-its.

- Remove doubles or similar skills.

- Have consensus about remaining skills

- Make 4 copies of each remaining post-it and place one set on each table of the 4 tables.

- Everyone uses 3 different colours post-its with own name on each: one colour is skill she masters, other was skill with average knowledge, and last one is skill she would like to learn.

- Everyone walks around and places all of his/hers post-it on one table on specific skills.

- After this first team composition, each team discussed if they are well-balanced compared to other teams and potentially discuss this with other teams directly, and make adjustments accordingly.

Internal and external focus

One of the biggest challenges was getting rid of statements such as: “We shouldn’t be responsible for these things, they (business, management, somebody else) should deal with it. If we deal with it, then we have less time to code”. For a long time there was a lack of external focus driven by combination of factors. The focus shifted very gradually with realisation that all those “external” things, such as understanding how users do their work in real life is crucial for delivering real value, and that working code itself is not necessarily same as value. Self-managing teams became significantly more efficient than anyone outside in dealing with these issues. There were no translations, no broken feedback loops because of e.g. technical limitations.

Growing multilearning team members

The teams were cross-functional and capable of taking care of all aspects for a full delivery. This was achieved quite early. What also happened is gradual cross-pollination of skills within each of the teams. Pair-work and overall collaboration enabled team members to learn new skills. At some point, almost all team members were capable of doing any of the disciplines and therefore became generalising specialists. E.g. in the beginning, testers were mainly building automated tests, but gradually started to deliver production code too. Operations guys from former operations team, spent most of their time coding since there was not much to do in operations.

Cross-component teams

When Scrum was introduced, teams were cross-functional, but still specialised in certain components. One team took care of messaging, other team dealt with “port map”, and yet another “ship inspections”. The PO would select a qualified feature team for a feature. In time, they started to become more cross-component, and therefore take care of any component required to deliver any feature. In time, any team was capable of doing anything. In other words, teams invested in deep learning in less familiar territory. Eventually, there was no significant difference between teams concerning knowledge areas.

A very interesting advantage is reduced architectural complexity. There was a less tendency to choose overly complex solutions. In contrary, more redesigns and refactorings are done in order to reduce cross-component complexity.

Coordination between teams

During the early days of “Scrum-But-But” (very fake Scrum) , there was a Scrum of Scrums meeting where the so-called Scrum Master of each team would come together with project managers to discuss topics. Ouch!

After some time, representatives from each team would come, and not necessarily the “Scrum Master”. In time, not much relevant was discussed in these meetings.

Eventually, as all project management related activities disappeared or replaced by Scrum activities, real coordination happened directly between team members as needed, and in many different ways. There was no special dedicated meeting for this. When needed, anyone could organise multi-team design workshops for any significant decision. Everyone is invited, but they were not compelled to participate.

Besides design workshops, we organised regularly coding dojos for knowledge sharing purposes, TDD katas, discussing some tricky approaches, etc. Because of strong generalising specialist culture and already strong collaboration between everyone, and being just a few teams together at the same site, there was no need for formal communities of practice. Rather, emergent multi-team coordination mechanisms were good enough.

Reporting

Scrum practices are the only means of reporting at HaMIS. Teams didn’t really report to anyone in any way. Line management existed, but was even further away. More than half of team members are contractors, and others were employees. Any direct line manager of team members didn’t really know what they were doing or had any influence on their work.

The most remarkable about this situation is that team members really felt part of HaMIS, and not their official organisation.

Cross-cutting activities

Decisions from workshops often led to some work (often, some supporting infrastructure work such as replacement of the application server or Java version upgrade) that is not related to a single feature. This work item was added to the bottom of the Product Backlog, and after the Product Owner’s consent during Sprint Planning, one of the teams would take the responsibility for delivery. This team becomes essentially a temporary infrastructure team for one or few Sprints, although we never named the team as such.

UI Design knowledge

In the beginning Scrum-But-But days, UI design was done by a dedicated technical “architect” who designed and developed the front-end of the system up-front in a proof of concept. He was not a UI design specialist. After Scrum introduction, this responsibility is fully given to teams. Therefore, anyone was allowed to make suggestions for user interface design and together as a team make a decision.

Unfortunately, this was not enough because none of members had proper knowledge and experience to do this really good. Everyone, PO, users, and teams were not happy with the design or resulting user experience, but nobody knew how to properly deal with the problem.

The solution was to hire a specialist to be a generalizing-specialist in her home team, but who in addition also acted as a teacher and coach to other teams. In the early days, she spent more time showing other teams a good design; later, she could spend more in pair-work or reviewing other teams’ UI designs.

Cross-team working agreements

All teams share one Definition of Done. This was inevitable since any team could deliver any of the features.

Any significant architectural decisions, which would immediately affect production code were first shared with other teams. Everyone was invited to discuss the solution, and attending team members were permitted to take decisions on behalf of everyone. Decisions making were almost always based on consensus, not compromise.

Anyone could suggest anything, and therefore could organise a session where significant decisions could be made. The person who made a suggestion had to have valid argumentation, which was challenged by others. Therefore, nobody except the Product Owner had special authority to force any decision, whether it was subtly based on too aggressive influencing or directly imposed.

Events

Sprint planning

At the start of the Sprint, all teams would first gather in front of a physical (cards on wall) Product Backlog where items for the upcoming 3 Sprints were always visible, together with the Product Owner. Each team would choose, negotiate with other teams and possibly clarify any cross-team coordination issues. In short, a common Sprint Planning part 1. The whole meeting took between 10 and 15 minutes.

The chosen items were then further discussed and planned by each team in their own Sprint Planning part 2. The PO was not always present during part 2 meetings, but could always be contacted by phone if needed.

LeSS rule: Sprint Planning consists of two parts: Sprint Planning Part One is common for all teams while Sprint Planning Part Two is usually done separately for each team.

Product Backlog Refinement

In the first year, we held a Product Backlog refinement (PBR) workshop with all teams all together. Everyone knew quite well all items, but it didn’t feel efficient. There was also not much collaboration. Team members felt guilty to speak up in an already inefficient meeting.

This was changed into a “gut feeling estimation” workshop, where everyone participated. In LeSS terms, multi-team PBR focusing on estimation. Teams would ask questions and discuss crucial points, where everyone continuously learned to stay out of details.

We had considered only representatives in the workshop, but the knowledge gained during this workshop proved to be very useful to everyone, and there were only a few teams.

After multi-team PBR focusing on estimation, each team did their own team-level PBR after choosing set of items most likely to be done by their own team.

A problem with this approach was that during Sprint planning, items could be switched between teams because of changing priorities or to remove constraints between teams. That’s good agility, but this would often require doing refinement all over again for this item by the new team.

In retrospect, the LeSS guide to hold an overall PBR meeting with representatives from each team, to due some lightweight clarification all together, would have reduced that problem. At least a few people from all teams would have had some exposure to all items, to increase flexibility across teams. But we didn’t try that.

LeSS Rule: Product Backlog Refinement (PBR) is done per team for the items they are likely going to do in the future.

LeSS Guidance: (1) Hold an overall PBR with representatives before each team PBR to explore which teams might work on which items, and to increase learning and alignment. (2) Hold a multi-team PBR to increase shared understanding and exploit coordination opportunities.

Retrospective

Right after the Sprint Review, each team held own team retrospective, which took 1 hour usually.

LeSS rule: Each Team has their own Sprint Retrospective.

After this retrospective, all teams got together for an overall retrospective. Each team presented own conclusions / actions they wished to communicate, and things they wished to discuss with other teams.

An example of a difficult to solve system-level issue was a big bang effect (not a minimal viable product) caused by prioritization in the product backlog. One or multiple teams had noticed that although the goal is to turn off the old product as soon as possible, they were working on items which didn’t seem to align with the stated goal. In other words, most important PBL items didn’t seem that important.

During the group retrospective, the issue is explained and action defined if other teams also agreed that issue should be resolved. The action is assigned to a specific person. This could be a team member, the PO, a Scrum Master, or a manager. In the above case, it was a PO who would tackle the problem together with teams during a next Overall PBR meeting. During this Overall PBR meeting, the teams would go into details of the problem, propose prioritization suggestions to PO, with reprioritization as a result.

In this process, the question was raised “Can we (teams) resolve this problem ourselves?” Only if not, the problem was given to someone else. Once an action is assigned, there was no specific process. It was suppose to be taken care of as soon as possible. Teams didn’t have a list of system-level issues or improvements, since they focussed on resolving them as fast as possible instead of keeping a list.

In a next group retrospective, everyone was reminded of actions from a previous retrospective and whether they were already done. It was usually only one system-level action and maximum three.

If action was given to a specific team, this team would usually place a post-it note on their Scrum backlog, next to other actions related to their team only.

LeSS rule: An Overall Retrospective is held after the Team Retrospectives to discuss cross-team and system-wide issues, and create improvement experiments. This is attended by Product Owner, Scrum Masters, Team Representatives, and managers (if there are any).

Sprint backlog & Daily Scrum

Every team used visual management for their Sprint Backlog and held their Daily Scrum in front of it. They were not held at the same time, to enable other teams to observe. There were often a few members from other teams.

LeSS rule: Each Team has their own Sprint Backlog.

Practices

ATDD

Teams started to use Fitnesse and several other tools already during Scrum introduction. It took some time before they learned to properly define tests, also without making a mess. At some point, they started to use Fitnesse to document specifications by using ATDD / Specification by Example practices. This happened at the beginning of the Sprint, together with PO, subject matter experts, or users.

Definition of Done

LeSS rule: The perfection goal is to improve the Definition of Done so that it results in a shippable product each Sprint (or even more frequently).

A Potentially Shippable Product Increment was brought into production after every Sprint (with few exceptions, which they felt as a big failure). Production deployment happened a few days after the Sprint was finished. This short process of about 1 hour didn’t involve HaMIS teams. Only travelling infrastructure expert, PO and external infrastructure provider were involved.

Everything else was part of the Definition of Done and done within the Sprint. It took us a lot of effort to achieve this. In time, this was more and more challenging because of growing complexity, and dependencies with other systems that were less agile than our group. This involved all testing (fully automated), customer documentation, deployment scripting, scripted production database changes, etc.

LeSS rule: One shared Definition of Done for the whole product.

Also, all supporting work was done by the feature teams. E.g. configuration, upgrades of all tooling.

Real DevOps: Elimination of the Separate Operations Group

When Scrum was introduced, three teams were building the new product, while a separate operations team of six people dealt with the existing system 24/7. When the first parts of the new system were released, this operations team took on responsibility for operations of the new one also. In the beginning, this was not much of a problem because the required availability of delivered features was not high. The development teams could usually take care of any problem the next day.

In time, HaMIS grew and larger changes were put in place. Although the operations team had limited or no Java experience, we all decided to introduce DevOps: to dissolve the separate operations team and spread operations people over HaMIS development teams and increase the responsibility of the feature teams to include operations. To start, the ex-operations people (now in feature teams) were still scheduled for 24/7 standby, just in case something happened in production. Gradually, the operations people would contribute more and more to HaMIS development. All of them were given an opportunity to learn from their teammates about Java and many applied practices and technologies.

On the other hand, as mentioned before, the new product definitely had issues entering production. Someone had to take care of those. The solution was to appoint one feature team as the operations team during one Sprint. Therefore, we didn’t have permanent operations team anymore, but a rotating team. A normal development team would temporarily become an operations team, in addition to doing normal feature development. They would take care of any issue and provide second-line support. In the beginning, this team would spend the whole Sprint on incidents, monitoring, issues, and so on. Since any developer would rather build something instead of solve self-created defects, all teams would spend time analysing and preventing these issues; this is popularly called “eating your own dog food”. Eventually, the number of issues dropped, even with growing system complexity. An “operations team” would start delivering more and more regular feature items. Ever more powerful Continuous Integration (behavior and system) helped a lot too.

By the way, the teams usually treated any work on infrastructure configuration as one or multiple tasks belonging to a Product Backlog feature-item. Even large infrastructure work was preferably split into smaller parts and done incrementally in the context of customer features.

Officially, the infrastructure was managed externally. In reality, the development teams were monitoring the whole infrastructure, introducing and scripting changes. The external company was more or less only executing tasks teams defined. We have spent a lot of effort in involving them in the process, thereby increasingly resembling a single team, and in the process removing this last functional unit dependency. Communication between the teams and the company was direct, through Skype, and one day per week a visit to our office.

Probably the most crucial cog in this was to have an infrastructure expert as a traveller between teams. He made sure that the delivery process was going smoothly and did most of the communication with the external service provider. Ideally, this work was not needed, but thanks to him we managed to deliver after almost every Sprint.

With this measure, this infrastructure and all other shared resource queues are removed. Teams were capable of fully delivering business or user requests into production. In the beginning there was one week between delivering the PSPI and the actual deployment on production. By having someone of the external company once a week at our location, the waiting time was decreased to about 2 days. Besides this, team did not have to wait for anyone to make a delivery.

IT management started also to realise that this was not a project anymore, but continuous product development. Especially in the last year, a massive influx of new requests resulted in new budgets being reserved. Mainly thanks to great results, the project-paradigm organisation rather silently transformed into a product-paradigm group.

Project management

Speaking of “projects”, In the early Scrum-But-But days, HaMIS had two project managers and one program manager, due to traditional assumptions within the larger organization still based on a project- rather than product-paradigm One of the project managers was an official HaMIS project manager while the other was mainly concerned with external communication and coordination with partially dependent projects in other companies or departments.

Unfortunately, these roles were imposed to remained after the reorganisation to a better Scrum adoption. This created some systemic conflict with the Product Owner, because the PO should have been fully responsible for communicating with external stakeholders, and coordination with other major parties. But the project managers and program manager also tried to do that.

However, they did help with administrative tasks such as producing traditional reports for traditional managers, and most important, ensuring everyone got paid ;)

Any organisational aspect concerning teams were done by teams, not managers, including: teams (re)design, hiring (except financial part) and firing people, significant architectural decisions, changing working processes. By the way, hiring was done via one full day hands-on evaluation by one of the teams. This included pair-programming, participation in Scrum meetings, and design workshops.

Effectively, although still there, the project and program managers were not part of the organization in any meaningful way, but would occasionally help by doing teams’ requests.