An article by Robert Briese, LeSS trainer and unFIX practitioner.

Organizational agility is no longer a luxury but a necessity in today’s fast-moving business landscape. As you already know from working with unFIX, a flexible organizational design can help teams adapt swiftly to change, spark innovation, and deliver value to customers more effectively. Yet, when it comes to scaling product development across multiple teams, many organizations struggle to align structure with execution in a clear, cohesive manner.

This is where LeSS (Large-Scale Scrum) comes into play. While unFIX offers a versatile pattern library for shaping and reshaping organizational designs, LeSS focuses on multi-team product development through minimal rules, clear principles, and empirically driven experiments rooted in Scrum. By introducing the LeSS rules and using the unFIX-designed structure, you can not only visualize and adapt your current organizational setup but also ensure that the day-to-day product-development processes are straightforward, aligned, and optimized for true organizational adaptability.

In this article, we’ll explore four essential insights that illuminate how unFIX and LeSS complement each other:

Shared Goal – Both aim to foster agility in organizations.

Differentiation – unFIX provides the pattern library for modeling and redesigning organizational structures, whereas LeSS represents an organizational system for product development with a set of fixed rules, core principles and various guides and experiments aimed at maximizing an organization’s adaptiveness.

Versatile Toolbox vs. Framework – While unFIX is a flexible toolbox for various optimization goals, LeSS is a more prescriptive set of rules and guides for an organizational design focused on maximizing value delivered to customers and end-users.

Processes – unFIX intentionally avoids prescribing processes, whereas LeSS adapts the simplicity of the Scrum rules for product development in a multi-team environment, emphasizing empirical process control.

I will show how combining unFIX and LeSS delivers powerful results, with unFIX giving you a clear picture of how your organization is structured and how it might evolve, and with LeSS, providing proven, lightweight governance for product development across multiple teams. The goal is to equip you with practical steps for introducing LeSS principles into an unFIX-modeled organization—helping you maximize both adaptability and value delivery in a large-scale setting.

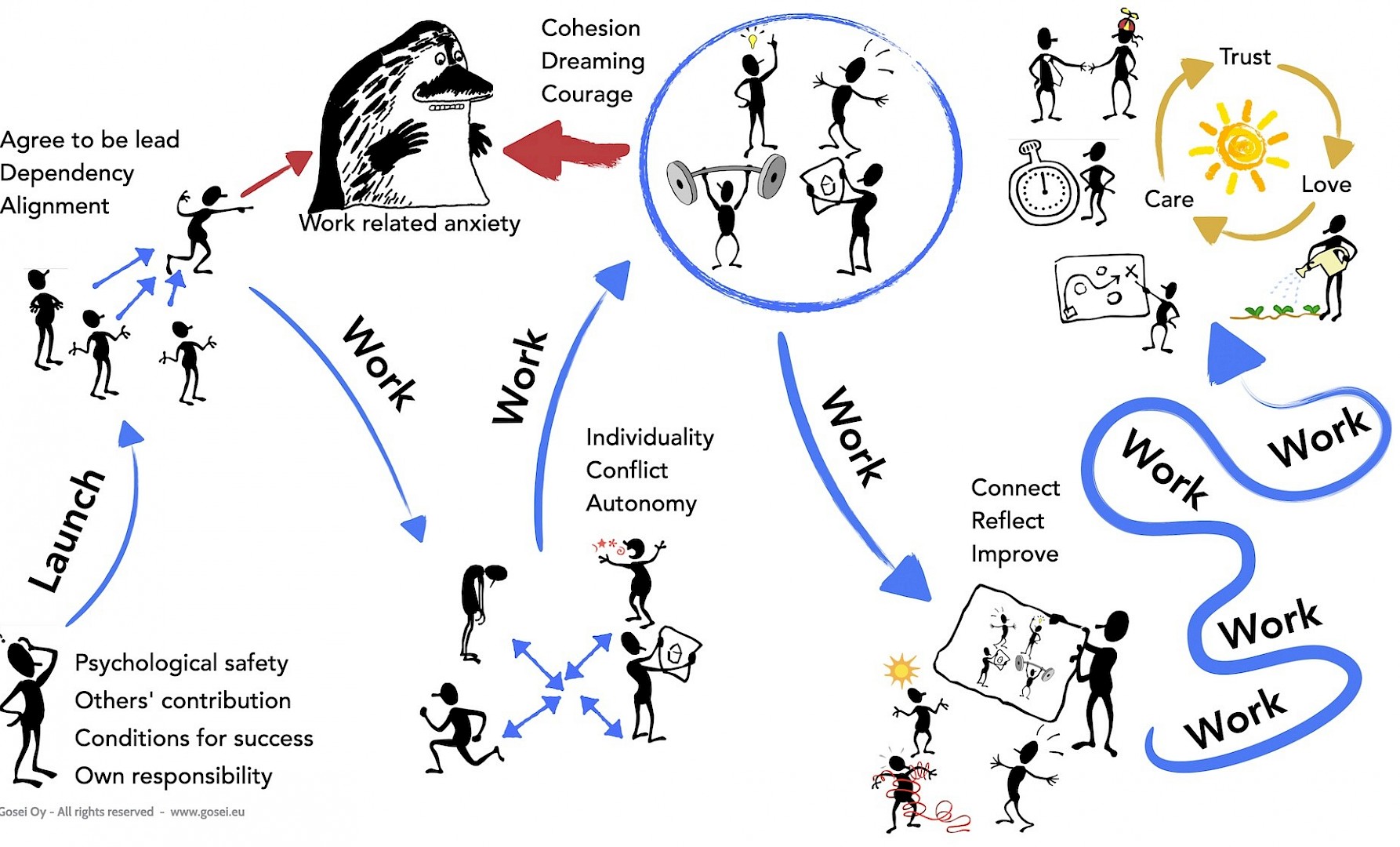

Five significant patterns that are essential for group dynamics in teams. They happen all the time and have an essential function in the beginning. Skillfully facilitating them, again and again, will gradually develop a culture of Trust, Care, and Love for the shared mental and physical space.

Our instinctive traits for working in smallish, co-located teams have evolved over thousands of years. The same human needs, behavior, and potential exist in remote teams and larger organizations but are invisible. Understanding them is essential for good leadership.

However, even co-located teams struggle in the workplace. The researchers Richard Hackman and Susan Wheelan, as well as popular writers Katzenbach and Patrick Lencioni, who actually studied teams, all open their books by stating that good Teamwork is rare.

Ikujiro Nonaka (1935-), the famous researcher of knowledge-creating organizations, researched and preached these bold words around 2000. Nonaka’s approach was to study real organizations and observe for successful patterns. For example, in 1984, after studying a handful of special projects, he coined the word Scrum in the sense we nowadays use it for the Scrum process.

Nonaka’s special interest was tacit knowledge, the unconscious or implicit knowledge. Formal concepts, language, and documents can convey explicit knowledge, but it is only the tip of the iceberg. Tacit knowledge is the invisible basis.

Tacit knowledge is only learned by imitation, by working together - by doing Teamwork. Trust, Care, and Love enable us to work with tacit knowledge.

Another researcher, William G. Ouchi, studied control mechanisms in organizations. He approaches from the opposite direction, stating that Teamwork is the only way to tackle novel, ambiguous, and interdependent challenges, where working with tacit knowledge is the key.