This is a cross-post from AgiliX blog post.

This blog is part of a series of peek previews from my upcoming book Coaching Agile Organisations.

This is the first part of a blog series about product definition in LeSS.

In large product development, teams tend to work on just a part of the real product. The part – a narrow product definition – is often a component or a specific activity in the development process; it is not a product.

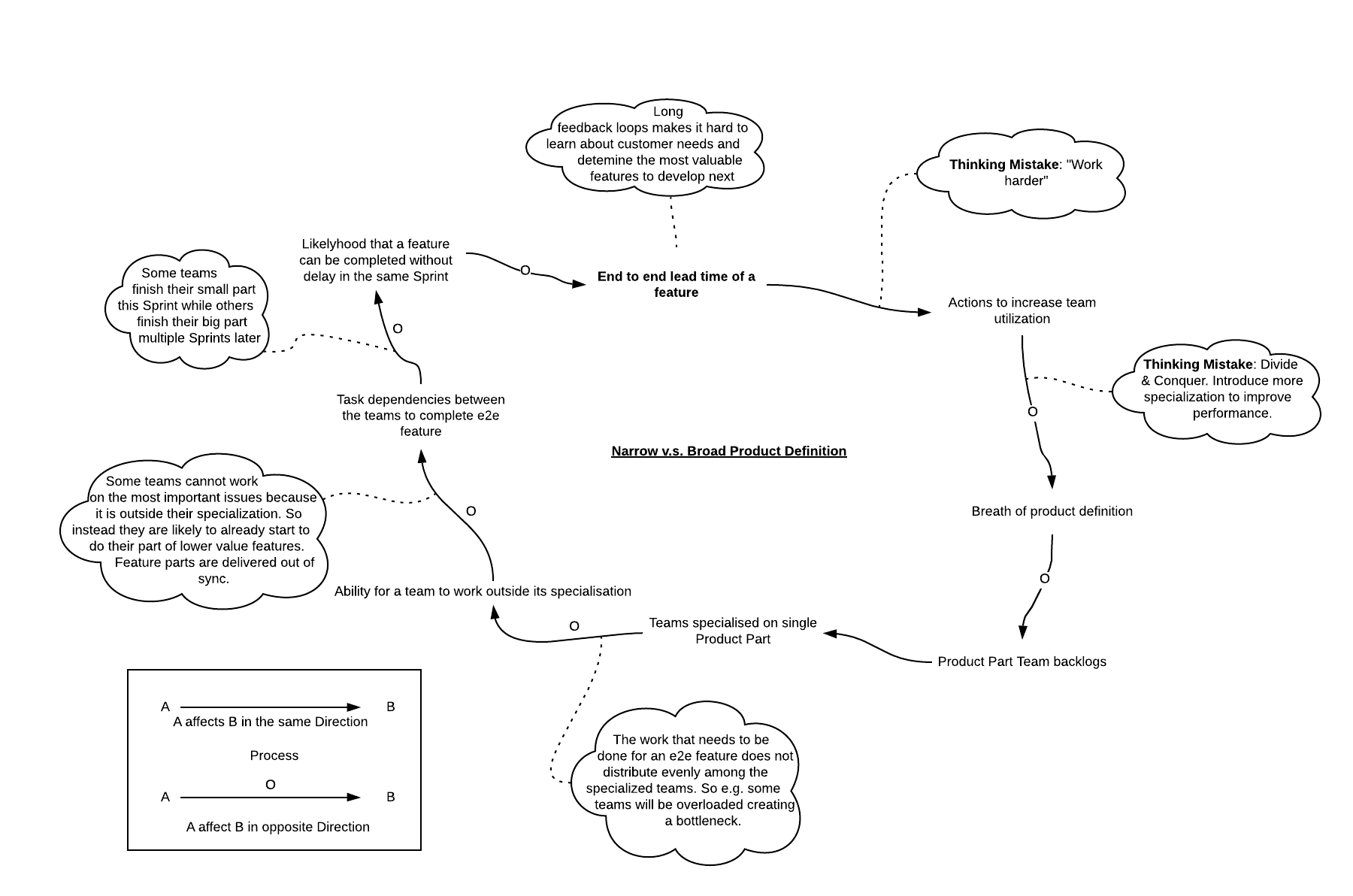

A narrow product definition creates all kinds of problems for a product group. It locally optimizes the performance of the teams at the cost of the performance of the group. The causal loop diagram (CLD) below explains this dynamic. (See this blog for a quick overview of CLD notation.)

Narrow product definitions make it more likely to have specialized teams that only work in their silo, which in turn decreases adaptability and speed of learning at the overall product level. Broader product definitions lead to teams that cover multiple components and activities that together address the needs of end-users.

A commonly used definition of a product is “something that is made to be sold.” The product provides a way of making a profit.

The product definition determines what organizational elements (people, components, processes, and systems) are needed to develop and run the product. If your product is Mortgages, then your Product Owner is probably a business person who understands the market. The Product Backlog might have items like “Loan offers to small businesses,” and the users are likely to be paying customers. Mortgages is a broad product definition when it contains all the parts needed to produce an end-to-end solution to the end customer.

The product definition includes multiple components, activities, and provides solutions to the needs and problems of end-users. You can define your product using the following two steps:

Step 1 – Identify the required organization elements to develop and sustain the product.

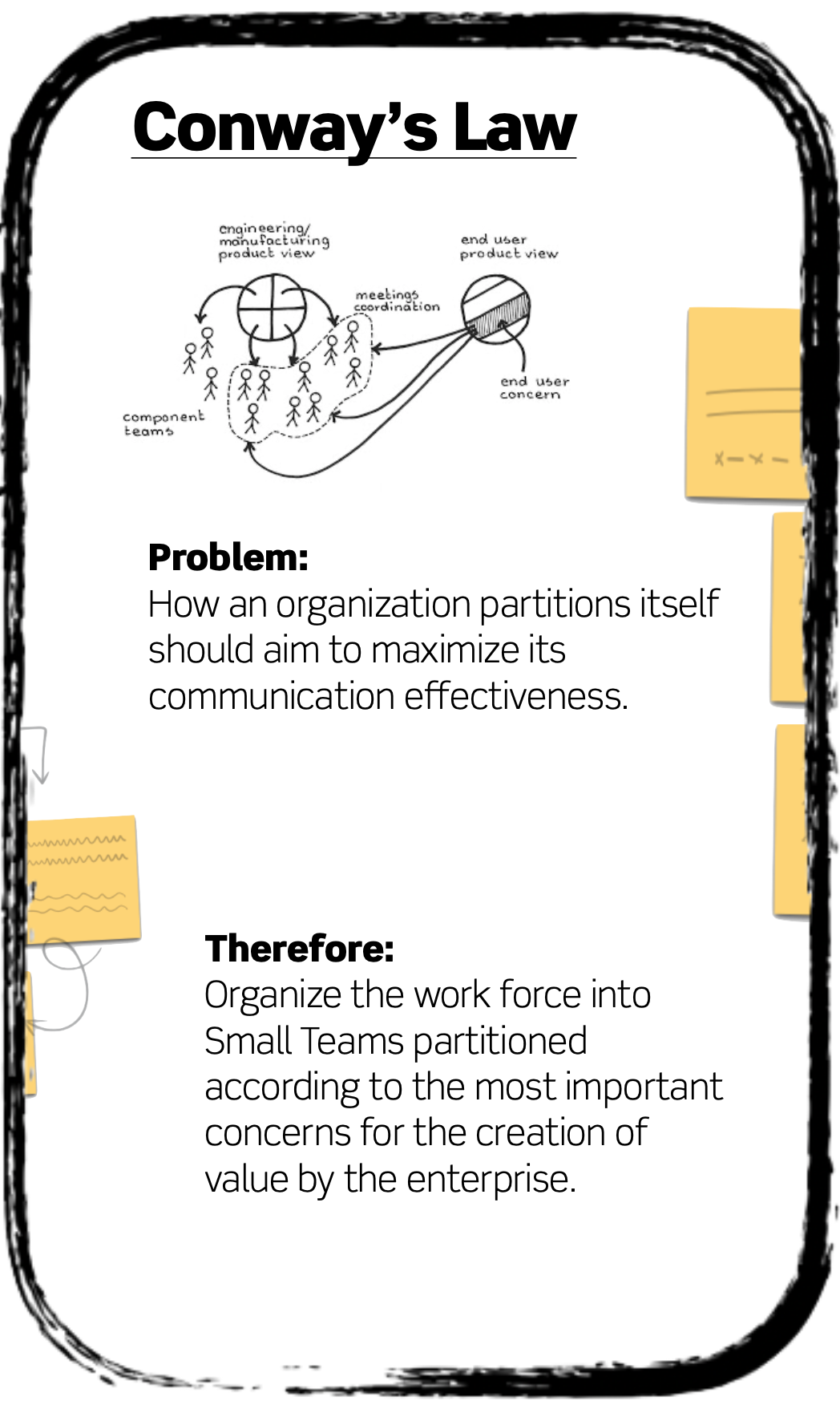

You start with the elements – your component teams – you currently call products, the activities, the people, and the processes you have presently in your group. You then study how the work works for your group so that you understand the types of dependencies that exist to develop, maintain, and sustain your product.

The typical steps to achieve this are:

Step 2 – Clarify the revenue streams

A proper product definition identifies a group broad enough so that it includes revenue streams. Without it, the teams in the group will likely be disconnected from market concerns where the real value lies, and instead, the teams focus only on the part of the whole product.

In this step we ask the question: Do the identified organizational elements produce a product that generates revenue for the organization? Or are there missing parts to do so? The way we prefer is to find answers to the following questions:

If you cannot give a meaningful answer to all of the questions above, then your product definition is too narrow, and you would need to expand it.

At this point, you identified a set of organizational elements that together produce value for end-users and have an independent revenue stream. The result typically includes tens of components, skills, activities, and it can involve hundreds of people in total.

With such a large group, you may ask yourself, “How can I create effective cross-functional teams that include all these capabilities?” In the case of more than around ten teams, we recommend to organize the teams among Value Areas and contain dependencies per area.

This is the topic of my next blog, part 2.