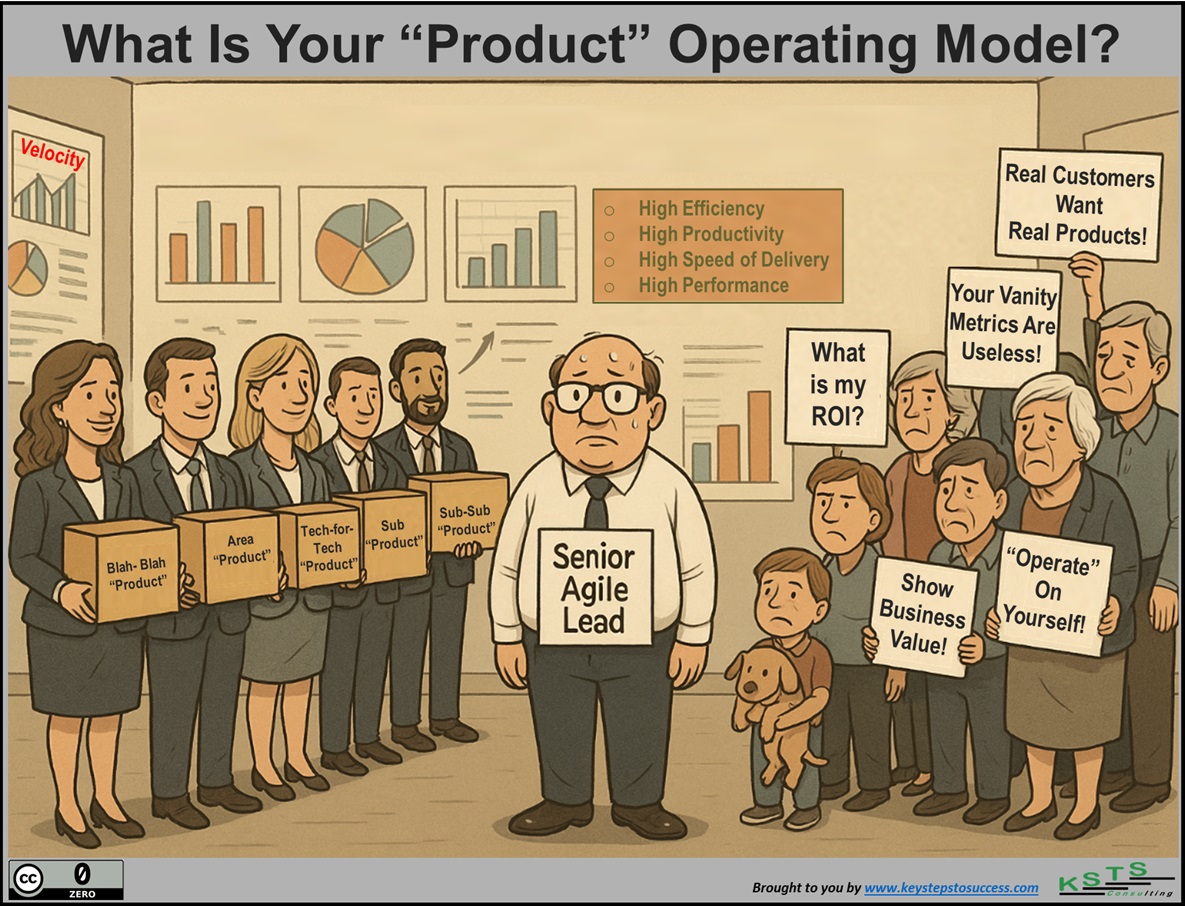

The Hidden Cost of High Performance - Why optimizing teams in isolation can cripple organizational outcomes

The Parts vs. System Paradox

“Changing parts will have little impact on the system. But changing interactions or purpose can create a massive impact.” — Steven Schuster

Systems thinkers have long understood this. So why do many organizations still obsess over optimizing individual teams — driving up local efficiency while system-wide performance stagnates or declines?

Here’s what happens:

- A team gets faster

- But what they produce isn’t aligned with what the customer actually needs

- Or worse, it clashes with what another team is doing

- You get work that’s faster, cheaper… and irrelevant

To improve real outcomes, stop focusing on parts. Start improving how the parts work together. Make collaboration worth it for individuals — not an extra burden, but a source of progress and shared wins.

_065_%20round%20copy.jpg?preferred_lang=it) by

by  by

by

by

by

by

by