Lean Thinking

I have enough money to last me the rest of my life, unless I buy something.

—Jackie Mason

Lean thinking is a proven system that scales to large development, as evidenced by Toyota and others. Although most often applied to products, it is also used in service areas—both within Toyota and in domains such as healthcare.

A metaphor (from Don Reinertsen, a lean advocate) we use to convey a key thinking mistake–and opportunity–is the sport of relay racing.

Consider a relay race. The racers are standing around waiting for the baton from their colleague. The accountant in the finance department, looking aghast at this terrible underutilization ‘waste,’ would probably mandate a policy goal of “95% utilization of resources” to ensure all the racers are busy and “productive.” Maybe—he would suggest—the runners could run three races at the same time to increase “resource utilization,” or they could run up a mountain while waiting for the baton.

Funny… But this kind of thinking lies behind much of traditional management and product development processes. In contrast, here is a central idea in lean thinking:

Watch the baton, not the runners.

Does your organization measure “productivity” or “efficiency” in terms of how busy people are, or how much time is spent watching the runners? Or does it measure “productivity” in terms of fast delivery of value to the real customer, thereby “watching the baton”? What is the value-to-waste ratio in your work? What are the impediments to the flow of value and how can people feel inspired to continuously strive to improve that flow? Lean thinking addresses these questions.

Lean Thinking: The Big Picture

Background

Lean (or lean thinking ) is the English name given by a Toyota engineer doing graduate work at MIT to the system now known as the Toyota Way. Toyota is a strong, resilient company that seems to improve over time. For example, in 2014 Forbes ranked Toyota both the largest and most valuable automotive company in the world. Extreme Toyota dedicates a chapter comparing their sustainable performance compared to others in their industry.

Toyota is far from perfect and there are unique things to learn from other systems that are not found in lean thinking. We are not suggesting that Toyota or lean thinking are the only models to learn from or to simply emulate. Nevertheless, it is a long-refined, effective system that comes from a relatively robust and sustainable company.

The Pillars of Lean Are Not Tools and Waste Reduction

There are some common misconceptions about lean. This section starts with clearing these away. What is the essence and power of lean thinking and Toyota?

When I first began learning about the Toyota Production System, I was enamoured by the power of [one-piece flow, kanban, and other lean tools]. But along the way, experienced leaders within Toyota kept telling me that these tools and techniques were not the key. Rather the power behind TPS is a company’s management commitment to continuously invest in its people and promote a culture of continuous improvement. After studying for almost 20 years…..this is finally sinking in. (emphasis added) [Liker04]

Wakamatsu and Kondo, Toyota experts, put it succinctly:

The essence of [the Toyota system] is that each individual employee is given the opportunity to find problems in his own way of working, to solve them, and to make improvements.

Management Tools Are Not a Pillar of Lean

The above quotes underscore a vital point because over the years there have been some ostensibly ‘lean’ promoters that reduced lean thinking to a mechanistic, superficial level of management tools such as kanban and queue management. These derivative descriptions ignore the central message of the Toyota experts who stress that the essence of successful lean thinking is “building people, then building products” and a culture of “challenge the status quo” via continuous improvement.

Reducing lean thinking to kanban, queue management and other tools is like reducing a working democracy to voting. Voting is good, but democracy is far more subtle and difficult. Consider the internal Toyota motto shown in a photo we took when visiting Toyota in Japan some years ago. It captures the heart of lean, summarizing the focus on educating people to become skillful systems thinkers:

To simplify lean thinking to tools is to fall into a trap repeated many times before by companies superficially and unsuccessfully attempting to adopt what they thought was lean.

… it was only after American carmakers had exhausted every other explanation for Toyota’s success—an undervalued yen, a docile workforce, Japanese culture, superior automation—that they were finally able to admit that Toyota’s real advantage was its ability to harness the intellect of ‘ordinary’ employees. [Hamel06]

Consequently, Lean Six Sigma is viewed by Toyota people to represent Six Sigma tools but not to represent real lean thinking. A former Toyota plant and HR manager explains:

Lean six sigma is a compilation of tools and training focused on isolated projects to drive down unit cost… The Toyota approach […] is far broader and far deeper. The starting point is the Toyota Way philosophy of respect for people and continuous improvement. The principle is developing quality people who continually improve processes. The responsibility lies not with black belt specialists but with the leadership hierarchy that runs the operation, and they are teachers and coaches. [LH08]

Waste Reduction Is Not a Pillar of Lean

The book Lean Thinking was justifiably popular and introduced some Toyota ideas to a much wider audience. We recommend it—while observing that it presents a condensed view of the Toyota system. Lean Thinking draws significantly on research from the 1980s and early 1990s that focused on Toyota’s production system, and was published before Toyota’s own Toyota Way 2001 that summarized the priority of the broader principles from an insider’s perspective. The subtitle of Lean Thinking is Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Organization, and so not surprisingly, those who have read only that one book often summarize lean as “removing waste.”

Although useful, waste reduction is not a pillar of lean. It is only mentioned several levels deep within the Toyota Way 2001 . Plus, in Lean Thinking , some preeminent lean principles such as Go See (highlighted in Toyota) are treated in an entertaining but only anecdotal or secondary style that make it possible to miss the relative importance of some lean principles within Toyota. Study Lean Thinking, and study more of the Recommended Readings.

The Two Pillars of Lean

What are the pillars of lean? Toyota president Gary Convis:

The Toyota Way can be briefly summarized through the two pillars that support it: Continuous Improvement and Respect for People. Continuous improvement, often called kaizen, defines Toyota’s basic approach to doing business. Challenge everything . More important than the actual improvements that individuals contribute, the true value of continuous improvement is in creating an atmosphere of continuous learning and an environment that not only accepts, but actually embraces change . Such an environment can only be created where there is respect for people—hence the second pillar of the Toyota Way. (emphasis added)

And from Toyota CEO Katsuaki Watanabe:

The Toyota Way has two main pillars: continuous improvement and respect for people. Respect is necessary to work with people. By “people” we mean employees, supply partners, and customers. …We don’t mean just the end customer; on the assembly line the person at the next workstation is also your customer. That leads to teamwork. If you adopt that principle, you’ll also keep analyzing what you do in order to see if you’re doing things perfectly, so you’re not troubling your customer . That nurtures your ability to identify problems, and if you closely observe things, it will lead to kaizen—continuous improvement. The root of the Toyota Way is to be dissatisfied with the status quo; you have to ask constantly, “Why are we doing this?” (emphasis added)

Respect for people and continuous improvement “challenge everything” and create an “embrace change” mindset. These pillars of lean are expanded later in this chapter. If a lean adoption program ignores the importance of these—what we would call a cargo cult lean adoption—then the essential understanding and conditions for sustainable success with lean will be missing.

Why “Lean”? Lean & the Toyota Way

The English term ‘lean’ was coined for the Toyota system to contrast mass production with Toyota’s not-mass production—lean production. The implication was a dramatic reduction in batch size, and no longer competing on economies of scale but rather competing on the ability to adapt, avoid inventory, and work in very small units—themes also found in LeSS.

Two of the authors of the The Machine That Changed the World went on to write Lean Thinking, a popular introduction that summarized five principles.

In their excellent books on lean software development, Mary Poppendieck—who applied lean thinking at 3M—and Tom Poppendieck raised awareness of the correspondence and complementary qualities of lean to agile software development methods. And Jeff Sutherland and Ken Schwaber, co-creators of Scrum, have studied Toyota and lean thinking.

Relatively broad descriptions of the lean system are The Toyota Way, The Toyota Product Development System, Inside the Mind of Toyota , Extreme Toyota, and Lean Product and Process Development. All are based on long study of Toyota. The Toyota Way text is used by Toyota for education, in addition to their internal Toyota Way 2001. This introduction to lean is similar to these descriptions.

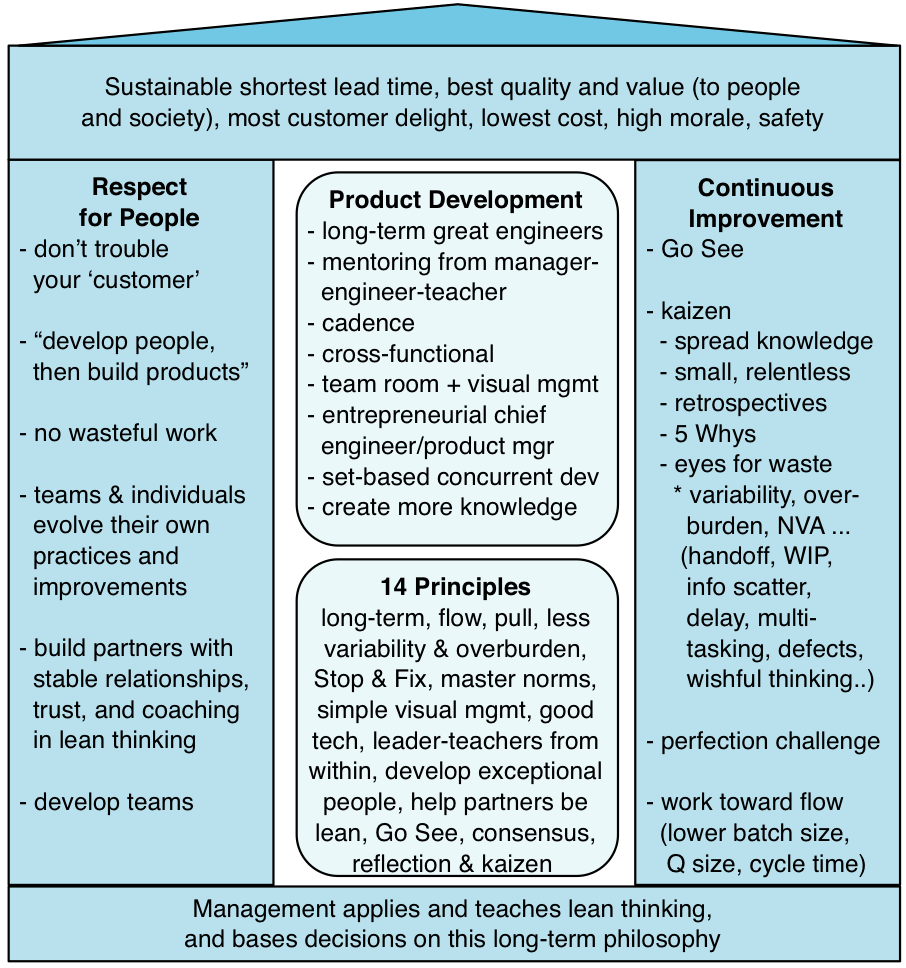

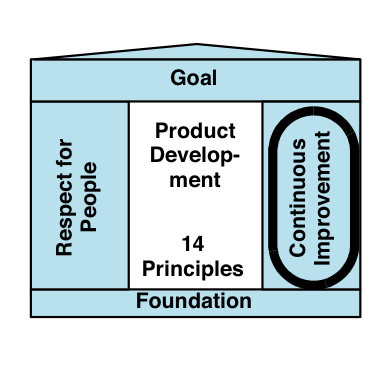

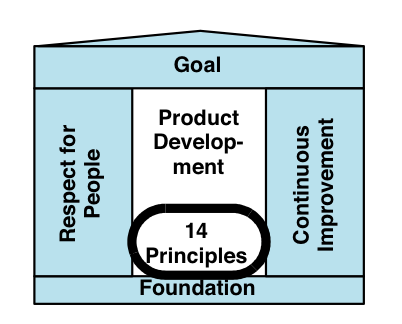

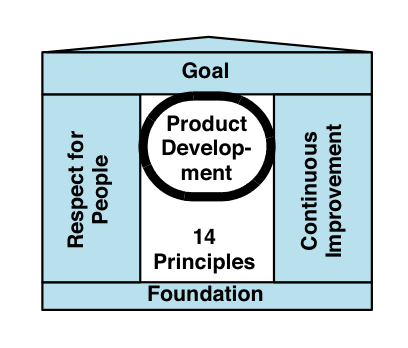

Lean Summary: The Lean Thinking House

The lean-thinking house summarizes the modern Toyota Way in a “house” diagram, because an earlier version of the Toyota system was first summarized within Toyota by a similar house diagram. This house also defines the major sections of this introduction, such as the 14 Principles. The remainder of this introduction follows the major elements of the diagram in the following order:

- lean goal

- lean foundation: lean-thinking manager-teachers

- respect for people

- continuous improvement

- 14 principles

- lean product development

Lean Goal

|

Sustainable shortest lead time, best quality and value (to people and society), most customer delight, lowest cost, high morale, safety. |

Broadly, the global or system goal of lean thinking at Toyota is to go from “concept to cash” or “order to cash” as fast as possible at a sustainable pace—to quickly deliver things of value (to the customer and society ) in shorter and shorter cycle times of all processes, while still achieving highest quality and morale levels. Toyota strives to reduce cycle times, but not through cutting corners, reducing quality, or at an unsustainable or unsafe pace; rather, by relentless continuous improvement , that requires a company culture of meaningful respect for people in which people feel they have the personal safety to challenge and change the status quo.

There are echoes of this goal in the words of the creator of the Toyota Production System (TPS), Taiichi Ohno:

All we are doing is looking at the time line, from the moment the customer gives us an order to the point where we collect the cash. And we are reducing the time line by reducing the non-value-adding wastes.

So, a focus of lean is on the baton, not the runners—removing the bottlenecks to faster throughput of value to customers rather than locally optimizing by trying to maximize utilization of workers or machines. This is the focus of Scrum as well—delivering valuable features each short timeboxed iteration.

Not only does Toyota (and their Lexus and Scion brands) manufacture vehicles, but also successfully and efficiently develop new products—lean principles apply to product development. How does Toyota achieve the “global goal” in their two main processes, product development and production?

- Development—out-learn the competition , through generating more useful knowledge and using and remembering it effectively.

- Production—out-improve the competition , by a focus on short cycles, small batches and queues, stopping to find and fix the root cause of problems, relentlessly removing all wastes (waiting, handoff, …).

This introduction returns to out-learn and out-improve later on. Of course, these approaches are not mutually exclusive. Toyota Development improves and Production learns.

Lean Foundation: Lean-Thinking Manager-Teachers

|

Management applies and teaches lean thinking, and bases decisions on this long-term philosophy. |

When we first visited Toyota in Japan, we interviewed people to learn more about their management culture and education system. One of the things we learned is that most new employees first go through several months of education before starting other work. During this period they learn the foundations of lean thinking, they learn to see ‘waste’ (a subject we will return to), and they do hands-on work in many areas of Toyota. In this way, new Toyota people…

- learn to “see the whole” (systems thinking)

- learn to see how lean thinking applies in different domains

- learn kaizen mindset (continuous improvement)

- appreciate a core principle in Toyota called Go See and gemba

Go See means people—especially managers—are expected to “go see with their own eyes” rather than sit behind desks or believe that the truth can be learned only from reports or numbers. It is related to appreciating the importance of gemba—going to the physical front-line place of value work where the hands-on value workers are.

We also learned that potential executive managers have worked their way up through years of hands-on lean thinking practice and mentoring to others. When Eiji Toyoda was president, he said to the management team, “I want you actively to train your people on how to think for themselves” [Hino06]. Note that this is not simply a message of let people think for themselves . Rather, the management culture is managers act as teachers of thinking skills . Toyota managers are educated in lean thinking, continuous improvement, root cause analysis, the statistics of variability, and systems thinking—and coach others in these thinking tools.

From this, we came especially to appreciate that for successful adoption of lean, there are management qualities needed for any meaningful, sustained success—the leadership team cannot “phone in” their lean support. Toyota is one of few companies that seems to demonstrate these qualities; to summarize:

- Long-term philosophy—many in the company are educated in lean thinking through courses and mentoring from manager-teachers.

- Long-term philosophy—virtually all management, including the executive level, must have a solid understanding of lean principles, have lived them for years, and teach them to others.

- Long-term philosophy—manager-teachers have cultivated systems thinking and process-improvement problem-solving thinking skills, and they teach it to others. The culture is imbued with the mentality and behavior, “Let’s stop and understand the root causes of problems.”

Manager-teachers—an internal Toyota motto is Good Thinking, Good Products. How do they achieve this “good thinking” which forms the foundation of their success? It is through a culture of mentoring. Managers are expected to be hands-on masters of their domain of work (the saying is, “my manager can do my job better than me”), are expected to understand lean thinking, and are expected to spend time teaching and coaching others. We learned during an interview in Japan that Toyota HR policies include analysis of how much time a manager spends teaching. In short, managers are less directors and more teachers in the principles of lean thinking, “stop and fix right,” and kaizen mentality. In this way, the Toyota DNA is propagated.

Atsushi Niimi, Toyota North America president, said that the greatest challenge in teaching the Toyota Way to foreign managers was, “They want to be managers, not teachers.”

The more one learns about lean, the more one appreciates that the foundation is manager-teachers who live and teach it and have long hands-on experience. The foundation is not tools or waste reduction.

Any company executive team that wants to succeed with lean development will need to pay attention to this basic lesson—that they cannot “phone in” their support to “do lean.”

Pillar One: Respect for People

|

This pillar of lean thinking is described in the Respect for People section of the separate LeSS principle of Continuous Improvement. |

Pillar Two: Continuous Improvement

|

This pillar of lean thinking is described in the separate LeSS principle of Continuous Improvement Towards Perfection. |

14 Principles

|

The 14 principles describe the details of the Toyota Way (lean thinking) system. |

To quote Fujio Cho, a chairman of Toyota:

Many good American companies have respect for individuals, and practice kaizen and other [Toyota] tools. But what is important is having all the elements together as a system . It must be practiced every day in a very consistent manner.

Part of this broader system is covered in the 14 principles described in the Toyota Way book that comes out of decades of direct observation and interviews with Toyota people.

|

1. Base management decisions on a long term philosophy, even at the expense of short-term financial goals. |

|

|

2. Move toward flow; move to ever-smaller batch sizes and cycle times to deliver value fast & and to expose weakness and hidden problems. |

see Work Toward Flow and Indirect Benefits of Reducing Batch Size and Cycle Time |

|

3. Use pull systems to avoid overproduction of WIP or inventory; decide as late as possible. |

see Pull Systems within Work Toward Flow. |

|

4. Level the work---reduce variability and overburden to remove unevenness. |

see Pull Systems within Work Toward Flow and Applying Queue Management in LeSS. |

|

5. Build a culture of stopping and fixing problems to ultimately build quality in; teach everyone to methodically study problems. |

Stop and Fix is a deep and repeating theme in lean thinking. And not a quick fix, but understanding root causes and introducing deep countermeasures. Here are some discussions of Stop and Fix in different processes and domains: software development and software integration and healthcare. |

|

6. Standardized tasks are the foundation for continuous improvement and employee empowerment. |

This is discussed in more detail in the Kaizen section of the Continuous Improvement Towards Perfection LeSS principle. As explained there, in lean thinking a standardized task does not mean a centrally-defined standard; it is some very temporary standard that a team or person has defined or acquired for themselves as step one in kaizen. |

|

7. Use visual controls (visual management) to reveal problems—and to coordinate. |

A key theme of visual control and visual management in Toyota is to use tangible, physical tokens, not software, for visualization of what's going on and to coordinate. Computers are only used relatively simply, to create a gigantic display of color (a signol), to display a single gigantic number, etc. The physical tokens may be pieces of paper, colored wood blocks, and so on. Physical visual management is widely used now in agile software development; here are some examples: Big Visible Charts in XP and visual management in agile development |

|

8. Use only reliable thoroughly-tested technology that serves your people and process. |

This principle is not so applicable in the context of leading-edge software development with rapidly changing technologies. That said, most software developers know all-too-well the pain of new and buggy tools, and can appreciate the motivation behind this principle. Where applicable, open-source software tools, libraries, and frameworks often help. |

|

9. Grow leaders from within who thoroughly understand the work, live the philosophy, and teach it to others. |

Note first that lean leaders are expected to thoroughly understand the work. A saying in Toyota is that "my manager can do my job better than me." In software development, that means a lean leader thoroughly understands modern development practices. And lean leaders don't delegate teaching lean thinking to the "lean coaches"; they are the lean experts and they teach it. Lean leaders from within is a good idea if your existing culture is already lean (e.g., the Toyota context). Otherwise, introducing external lean experts is probably necessary. See Lean-Thinking Manager-Teachers |

|

10. Develop exceptional people and teams who follow your company’s philosophy</em>. |

This reflects the Toyota “build people, then products” message. It includes the lean-product-development principle of “towering technical competence.” |

|

11. Respect your extended network of partners by challenging them to grow and helping them improve. |

Bring partners (suppliers) into lean thinking as well. There is an emphasis on helping them improve and growing together for mutual long-term benefit. |

|

12. Go see for yourself at the real place work to thoroughly understand the situation and help. |

|

|

13. Make decisions slowly by consensus, thoroughly considering all options; implement decisions rapidly. |

Consensus building and considering all options are well-known concepts, but how many people have strong skill in these areas, and how many groups do this effectively? Falling into the habits of command and control or going along with the crowd are common reactions when this path is slow and difficult. Once a decision is made, execute fast! |

|

14. Become and sustain a learning organization through relentless reflection and kaizen. |

See learning organizations and kaizen. In LeSS, the system-level reflection happens every Sprint at the Overall Retrospective. |

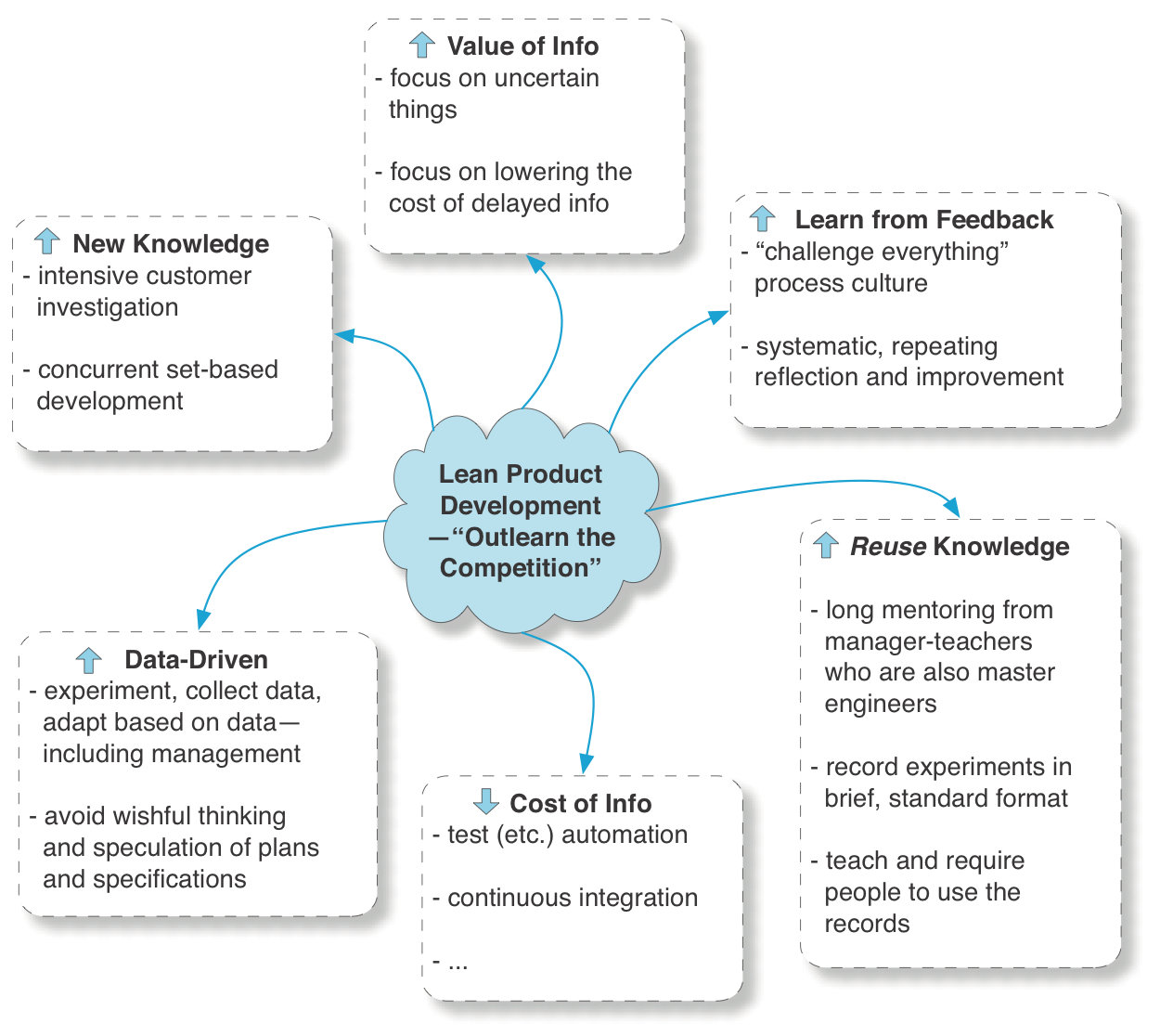

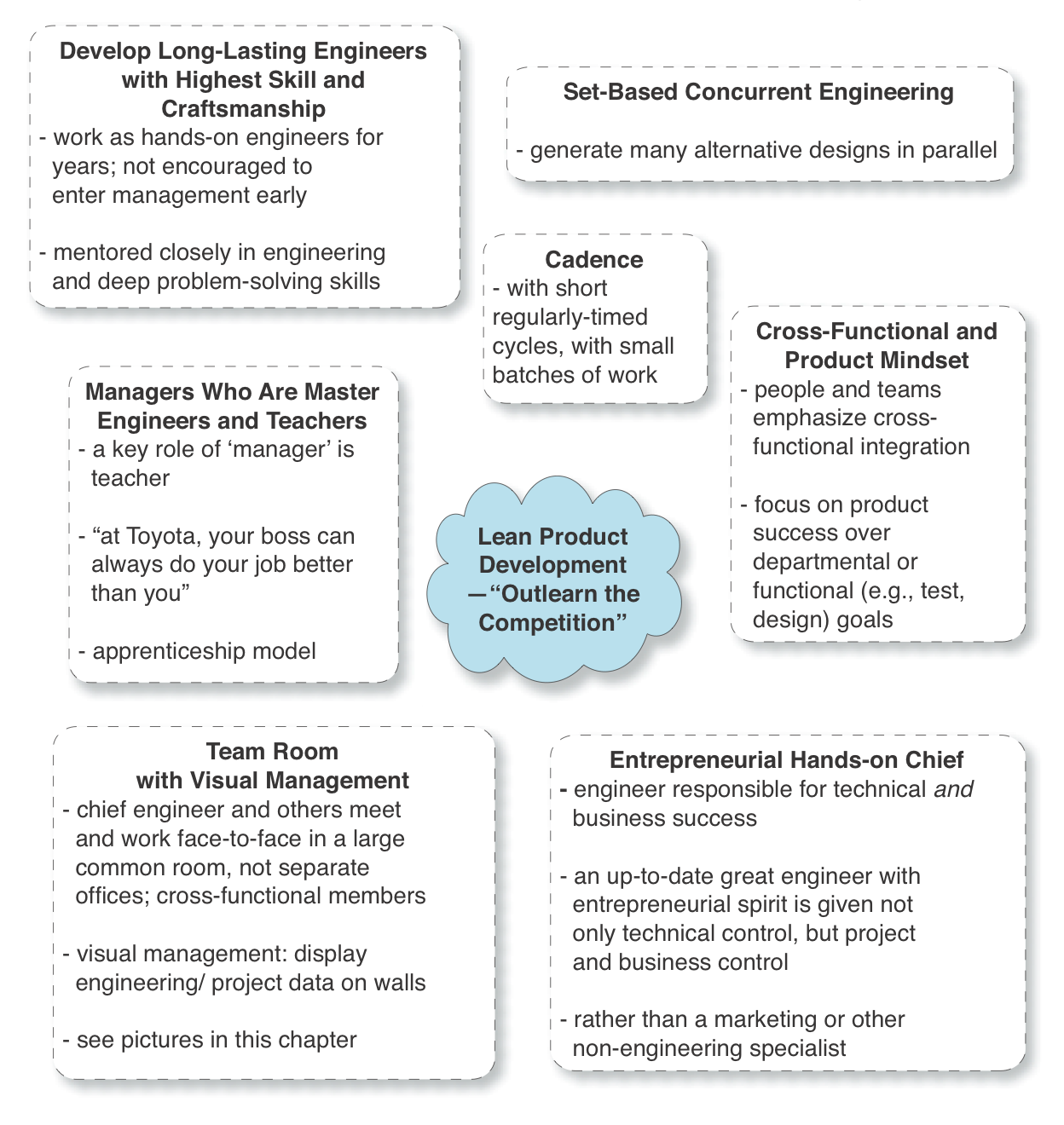

Lean Product Development

|

In addition to the 14 principles, what are the principles and practices to "outlearn the competition" specific to lean product development? |

Toyota people execute two key processes well, (1) product development and (2) production. University of Michigan researchers did a three-year study of Toyota and North American companies product development effectiveness [LM06]. Results? …

For example, the average die design-to-complete duration was five months for Toyota engineers and twelve months for the competition. All this, while maintaining the lowest R&D-to-sales ratio of any major automotive company in the world, due to the effectiveness of their development practices.

How do they do it? What is a focus of lean product development?

Outlearn the competition

For example, when Toyota developed the hybrid Prius, what did they create?

- the design of the car (and implementation of embedded software); in development they have a knowledge value stream to create a profitable production value stream

- knowledge orinformation—about customers, alternatives, experiments

Lean product development (LPD) focuses on creating more useful knowledge and learning better than the competition. Also, leveraging that knowledge and not wasting the fruits of the effort by forgetting what has been learned.

Not all new knowledge or information is valuable; the ideal is to create economically useful new information [Reinertsen97]. This is challenging because it is a discovery process—you win some, you lose some. A general lean strategy, based on a simple insight from information theory, is to increase the value of information created and lower the cost of creating knowledge .

Higher-value information—Several ideas in lean and agile development help. For example:

-

Focus on uncertain things—In Scrum, one prioritization guideline is to choose to implement and test unclear orrisky things early. The value of the feedback is high precisely because the outcomes are less predictable—predictable things do not teach us much.

-

Focus on early testing and feedback—Information has a real cost of delay, which is one reason why testing only once at the end of a long sequential cycle—motivated by the misguided local optimization of believing that it will lower testing costs—is almost always unskillful. It can be very costly to discover during stress performance testing, after 18 months of development, that a key architectural decision was flawed. In lean (and in Scrum), short cycles with early feedback loops are critical; by implementing less predictable things early and in short cycles that include testing, the cost of delay is reduced.

Lower-cost information—The Indirect Benefits of Reducing Batch Size and Cycle Time examines how adopting lean and agile principles ends up reducing the overhead cost of processes. In fact, one can broadly look at these methods as succeeding by lowering the cost of change —competing on agility. And that includes lowering the cost of learning. For example:

-

Focus on large-scale test automation—to learn about defects and behavior. The setup costs are non-trivial (if you are currently doing manual testing) but the re-execution costs are almost zero.

-

Focus on continuous integration—to learn about defects and lack of synchronization. By integrating frequently in small batches, teams reduce the average overhead cost due to the nonlinear effort-impact of integrating larger sets of code.

-

Focus on mentoring from experts and spreading knowledge—to reduce the cost of rediscovery.

Lean-Product-Development Practices

Cadence

Working in regular rhythms or cadence is a lean principle, both in production and development [Ward14]. A steady heart beat. In lean production, it is called takt time. In development, it is called cadence. The Scrum practice of delivering (and holding predictable meetings) in a regular-duration timebox illustrates cadence. Cadence is a powerful principle in lean product development, so the subject is examined in some detail…

There is something basic and very human about cadence: People appreciate or want rhythms in their lives and work—and appreciate or want rituals within these rhythms [Kerth01]. Most of us work in a cadence of seven-day weeks. There is the Tuesday-morning weekly meeting ritual. And so on. Simply, cadence at work improves predictability, planning, and coordinating. At a deeper level, it reflects the rhythms by which we live our lives.

In large groups adopting LeSS—groups that previously had little or no total-system cadence and long unbounded work—it is common to hear people say, “A common short Sprint was the most beneficial things we’ve adopted.” This reflects how much people appreciate cadence.

Suppose a group were not working in a timebox, but they can potentially deliver a running tested system any hour of any day (which is a great place to be). Suppose they want to hold coordination planning meetings (because several teams are involved) and they want to hold overall retrospectives. Their two options are (1) to hold these events semi-randomly over time, or (2) to hold them at regular intervals. This lean principle suggests the latter choice.

Cadence and Timeboxing

One popular approach to improve cadence is timeboxing (which is used in LeSS), a fixed—and usually short—cycle time of development work, such as a two-week timebox. Teams are expected to deliver or demonstrate something at the end of the fixed duration—something small and well-done rather than large and partially done. The duration may not change, but the scope of work can vary to fit the timebox.

Timeboxing is not a panacea for all knowledge-work problems, but it has advantages:

-

Timeboxing enforces cadence.

-

Development work is often fuzzy unbounded (or weakly bounded) work. When the team knows that the timebox ends on March 15, it bounds the fuzzy work and increases focus. So, timeboxing limits scope creep, limits gold-plating, and increases focus.

-

Timeboxing reduces analysis paralysis.

-

Suppose you are in university and have an assignment due on Monday. When do you start? For many, the answer is, “Close to Monday.” This is called Student Syndrome [Goldratt97] and timeboxing is a counterbalance.

-

If teams must deliver something well done in exactly two weeks, the waste and ineffectiveness in current ways of working become painfully clear. Timeboxing creates a change-force to improve. This is the “lake and rocks” improvement effect covered in Indirect Benefits of Reducing Batch Size and Cycle Time.

-

Timeboxing simplifies scheduling.

-

Humans are probably more sensitive to time variation than to scope variation—“It was late” is remembered more strongly than, “It had less than I wanted.” Timeboxing avoids the erosion of confidence that happens for business stakeholders when product development people say, yet again, “… maybe in one more week it will all be done.”

Re-use Information or Knowledge

How?

-

A culture of mentoring by master engineers and manager-teachers to re-use information.

-

Communities of Practice (CoPs) that spread knowledge laterally. CoPs are a LeSS organizational element.

-

Modern Web-centric tools such as wikis.

-

Learning and communicating design patterns in both hardware and software. These leverage the use of existing design insight.

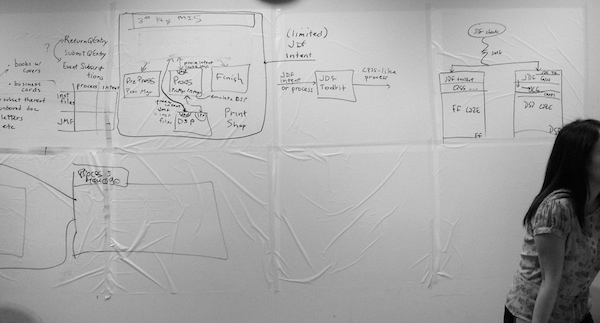

Obeya: Dedicated Room with Visual Management

Lean product development encourages a team room (or “big room”—big enough for a team) without internal partitions or walls, where a cross-functional team works and meets, and the entrepreneurial chief engineer sits. Walls are covered with large physical displays of project and engineering information, to support visual management. The team room is in contrast to people working in separate offices or cubicles with communication barriers such as partitions between the team members. Obeya is not the same as a large open-space configuration. It implies there is a dedicated room for a cross-functional team, whose walls are used for visual management.

A variation to traditional fixed walls is rolling whiteboards, as in this photo…

Entrepreneurial Chief Engineer with Business Control

In many (perhaps, most) product organizations, a product management group is responsible for the business goals and feature selection, and the members are not master engineers with up-to-date and profound technical depth. Toyota does things differently. Their product development is led by one great chief engineer with “towering technical excellence” who is also attuned to and responsible for the business success of the new product. In Toyota, product and engineering leadership is combined in one entrepreneurial chief engineer who understands the market, product management, the profit, and the engineering.

Set-Based Concurrent Engineering

Have you seen development as follows? … Pick or prototype one solution or design (one user interface, one architecture, …)

Set-based concurrent engineering is also called set-based design, and it’s different. For example, rather than one engineer or team creating one cooling system design, several alternatives may be explored at Toyota in parallel by different teams—and so too for other components. These sets of alternatives are explored and combined, and gradually filtered in cycles, converging on a solution from what was at first a large set of alternatives, then a smaller set, and so on. They outlearn the competition by increasing alternatives and combinations.

In software, a step in this direction is to explore at least two alternative for non-trivial design elements. For example, we worked with a team that had to build a handler for a printing protocol called JDF. Rather than all getting around one wall of whiteboards and doing one design as one team, we split into two groups and worked at two giant whiteboards (agile modeling) at opposite ends of the team room. Every 45 minutes or so we visited each other’s wall designs and did “show and tell”—collecting ideas from each other. Toward the end of the day, we got together, looked at the two design ideas (that covered large whiteboards), and decided which of the two was more appealing. Then the team implemented it, taking inspiration from this design idea sketched on the wall.

The spirit of set-based design, if not as elaborate as at Toyota, can be applied to many design problems. You can prototype, in parallel:

- two or three user interface alternatives

- two alternatives for a performance-critical component, …

Can Lean Production Lessons Help Development?

New product development (NPD) or research and development (R&D) is not predictable repetitive production (manufacturing), and the assumption they are similar is one cause of the misuse of early-1900s manufacturing “economies of scale” management practices in R&D; for example, sequential development and big batch transfers of requirements.

Yet, some of the principles and ideas applied in lean production—including short cycles, small batches, stop-and-fix, visual management, and queueing theory—are successfully applied in lean development. Why? Modern lean production is different, the small batches, queues, and cycle times in part reflect queueing theory insight (among other sources of insight)—a discipline that was created for the variable behavior in networks that is much more like development than traditional manufacturing.

An irony in some product organizations is that the manufacturing engineers have revolutionized and adopted lean production, moving away from “economies of scale” toward flow and flexibility in small batches without waste. But these lessons—which fit well to NPD—remain unused by R&D management, who continue to apply practices found in older economies-of-scale manufacturing management.

All that said, a caution: NPD is not manufacturing, and analogies between these two domains are fragile. Unlike production, NPD is (and must be) filled with discovery, change, and uncertainty. Some variability is both normal and desirable in new product development; otherwise, nothing new is done. So naturally, lean thinking includes unique practices for development.

Conclusion

As you investigate lean thinking, it is easy to see that it is a broad system that intersects with agile principles, and spans all groups and functions of the enterprise, including product development, sales, production, service, and HR. Lean thinking applies to large-scale product development—indeed, it applies to the enterprise .

Lean thinking is much more than tools such as kanban, visual management or queue management, or merely elimination of waste. As can been seen at Toyota, it is an enterprise system resting on the foundation of manager-teachers in lean thinking, with the pillars of respect for people and continuous improvement. Its successful introduction will take years and requires widespread education and coaching. To re-quote Fujio Cho, a chairman of Toyota:

Many good American companies have respect for individuals, and practice kaizen and other [lean] tools. But what is important is having all the elements together as a system. It must be practiced every day in a very consistent manner.

Recommended Readings

-

Dr. Jeffrey Liker’s The Toyota Way is a thorough cogent summary from a researcher who has spent decades studying Toyota and their principles and practices.

-

Inside the Mind of Toyota by Professor Satoshi Hino. Hino spent many years working in product development, followed by an academic career. Hino has “spent more than 20 years researching the subject of this book.” This is a data-driven book that looks at the evolution and principles of the original lean thinking management system.

-

Extreme Toyota by Osono, Shimizu, and Takeuchi is a well-researched analysis of the Toyota Way values, contradictions, and culture, based on six years of research and 220 interviews. It includes an in-depth analysis of Toyota’s strong business performance. Hirotaka Takeuchi was also co-author of the famous 1986 Harvard Business Review article “The New New Product Development Game” that introduced key ideas of Scrum.

-

Lean Product and Process Development by Allen Ward and The Toyota Product Development System by Liker and Morgan are useful for insights into development from a lean perspective.

-

Toyota Culture by Liker and Michael Hoseus. Hoseus has worked both as a plant manager and HR manager at Toyota, bringing an insider’s in-depth understanding to this book on the heart of what makes a lean enterprise work.

-

Lean Thinking by Drs. Womack and Jones is an entertaining and well-written summary of some lean principles by authors who know their subject well. As cautioned earlier in this chapter it presents an anecdotal and condensed view that may give the casual reader the wrong impression that the essential key of lean is waste reduction rather than a culture of manager-teachers who understand lean thinking and help build the pillars of respect for people and continuous improvement with Go See and other behaviors.

-

The Machine That Changed the World: The Story of Lean Production by Womack, Jones, and Roos was based on a five-year study at MIT into lean and the Toyota system.

-

Workplace Management by Taiichi Ohno is a short book by the creator of the Toyota Production System. It was out-of-print but has been recently re-translated by Jon Miller and is now available. The book does not talk much about TPS but it contains a series of short chapters that show well how Taiichi Ohno thought about management and lean systems.

-

Mary and Tom Poppendieck’s books Lean Software Development and Implementing Lean Software Development are well-written books that make important connections between lean thinking, systems thinking, and agile development.