Thinking About Testing

Testing can be used very convincingly to show the presence of bugs,but never to demonstrate their absence.

—Edsger Dijkstra

Testing no longer means testing

Confused? We can imagine! The purpose of testing used to be fairly clear–“Testing is the process of executing a program with the intent of finding errors” [Meyers79]. This changes when adopting agile and lean development.

Concurrent engineering necessitates parallelizing work. Dedicated cross-functional teams encourage single-specialists to broaden their expertise. These cause the purpose of conventional development activities–such as test–to shift.

At the code level, practices such as (unit) test-driven development blur the division between test and design as is made explicit by agile leader Ward Cunningham’s statement:

“Test-first coding is not a testing technique.”

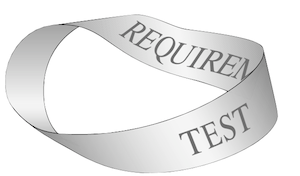

Acceptance test-driven development fuzzes the distinction between test and requirements analysis . In their IEEE Software article, “Test and Requirements, Requirements and Test: A Möbius strip,” Martin and Melnik argue…

… for early writing of acceptance tests as a requirements-engineering technique. We believe that concrete requirements blend with acceptance tests in much the same way as the two sides of a strip of paper become one side in a Möbius strip. In other words, requirements and tests become indistinguishable, so you can specify system behavior by writing tests and then verify that behavior by executing the tests.

This blurring of boundaries is fraught with fallacies. Adopting (unit) test-driven development as a testing technique misses the point and drives superficial adoption. Likewise, we regularly need to clarify to testing groups that they cannot adopt acceptance test-driven development without involvement of others.

Testing is no longer testing.

Challenge assumptions about testing

As touched upon, testing discussions are rife with assumptions. Challenge these! To be clear, we are not saying that these assumptions are false, but that leaving them unchallenged will limit thinking and the ability to improve. Deeply rooted in the Toyota culture is a pillar of the Toyota way: continuous improvement by challenging everything. Taiichi Ohno (a founder of lean thinking) said:

If you’re going to do kaizen continuously… you’ve got to assume that things are a mess. Too many people assume that things are all right the way they are… Kaizen is about changing the way things are. If you assume that things are all right the way they are, you can’t do kaizen. So change something!

What assumptions? Some of the beliefs webump into :

- testing must be independent and thus separated from development

- testing cannot start before coding is finished

- testing follows the sequence of (1) test case design, (2) test case execution, (3) test case reporting (a test waterfall)

- there must be a separate test department

- there must be a test manager

- testing must be done at the end

- testing must be “well planned”

- there must be a “testing strategy” and a “master test plan”

- 100% coverage is too expensive

- 100% test automation is too expensive

- testing requires a sophisticated test-management tool

- testing must be done by ‘testers’

Leaving these assumptions unchallenged retains in-the-box thinking. As long as you believe “Testing can only start after coding is finished,” you will never consider innovative ways of doing testing earlier. But once you are conscious of your assumption, you can question it and ask, “Is there any way I could work differently so that testing starts before coding is finished?”

Avoid using complex testing terminology

A question we enjoy asking big product groups is, “What do you all need to do before you can ship your product?”

Long ago, we learned that we need two columns: one for ‘normal’ activities, and a larger one for testing activities. The first column fills up with items such as coding, creating the users documentation, developing hardware, pricing, and training sales personnel. The second column comprises test activities , test levels , or test classifications . Common entries in the second column are shown below:

- unit test

- functional test

- stress test

- interoperability test

- load test

- installation test

- monkey test

- documentation test

- module test

- system test

- stability test

- compatibility test

- traffic test

- security test

- exploratory test

- acceptance test

- developer test

- integration test

- regression test

- reliability test

- performance test

- capacity test

- usability test

- user-acceptance test

Keep testing classifications simple

Straightforward terminology inspires intelligent behavior. For example, technology-facing tests that support the team are normally done by programmers during coding, while customer-facing tests that critique the product are usually done by a person other than the original author and are executed right after some user-functionality is implemented.

Two groups:

Developer test –these are usually created by the person who is implementing. The purpose is to check whether the code is doing what the programmer wants. If the tests pass, it means that the system does what the developer intended–but this does not necessarily mean it does what the customers wants.

Customer-facing tests –these test whether the requirements are fulfilled. They are frequently implemented and executed by a person other than the one who wrote the code. In this grouping, non-functional tests are classified as customer-facing tests because non-functional requirements for large systems are typically explicit and the most important.

Don’t separate development and testing

Bill Hetzel, the organizer of the first software testing conference, defined in The Complete Guide to Software Testing six principles of testing. The sixth principles–test independence–is a common theme throughout the history of software testing. Glenford Meyers, author of the first book on software testing, stressed the independence of testing in Software Reliability :

Testing should always be done by an outside party who is somewhat detached from the program and project… System testing should always be done by an independent group such as a separate quality-assurance department.

Why is separation important? Some frequently stated arguments:

- Programming is constructive whereas testing is destructive–thus, programmers cannot test.

- If programmers test their own code, then they will change the test according to the implementation.

- When testing is done by the same group as implementation, then they can meet their deadline by skipping testing.

The first two arguments assume single-specialist teams rather than cross-functional teams. The last argument suggests a quick fix for the much larger problem of quality-destroying shortcuts when pressuring developers.

In these arguments, test independence is equated to test separation from development. However, Hetzel clarifies the principle:

The requirement is that an independence of spirit be achieved, not necessarily that a separate individual of group do the testing.

This point is reiterated in Agile Testing in which the authors also point out the suboptimization created by separating testing:

Teams often confuse “independent” with “separate.” If the reporting structure, budgets, and processes are kept in discrete functional areas, a division between programmers and testers is inevitable. Time is wasted on duplicate meetings, programmers and testers don’t share a common goal, and information sharing is nonexistent.

Test independence does not mean independent testers.

How to achieve test independence in spirit without separating testing? By writing tests before implementing code . The test cannot be influenced by the implementation, because it does not exist yet. This way, test-driven development achieves the spirit of independence without separation of departments.

Testers and programmers work together

Separating testing from development often leads to a conflict between programmers and testers. Testers–hunting for bugs–try to prove that part of the program is faulty. Programmers–with their ego in their code–defend themselves, their code, and the program. Probably everyone who has been in the role of a tester in a test department has experienced this.

In a Scrum team, ‘testers’ are no longer testers but ‘simply’ members of the team–with testing as their primary specialization . ‘Programmers’ are any members of the team who can code. Every member of the team has a shared goal and is held–as a team–accountable to that goal. Team members with different primary specializations have to cooperate in order to reach that goal.

Educate and coach testing

Good testing skills come with deliberate practice and time. Unfortunately, especially in large organizations, testing skills are not respected. “Everybody can do that” is their belief, so they offshore it to a company that grabs people randomly from the street and assigns them to test. Random people hired to bang away on an application routinely see their job as a temporary stage they need to go through before advancing to a “real job.” They do not bother deepening their testing skills and so contribute to the false belief that testing is trivial.

Testers who don’t bother to learn new skills and grow professionally contribute to the perception that testing is low-skilled work. [CG09]

Falling into the “testing is trivial” trap is costly. Support testing mastery by providing self-study material, education, and coaching. We have listed some general testing-skills literature in the recommended reading section.

Of course, providing education and coaching in testing is also important to traditional environments. In cross-functional teams, this becomes even more relevant as testers at times feel marginalized. Not having a testing functional organization may impact the feeling of career progression and their interest in testing. And this is exacerbated if all education and coaching is related to development or management practices. High test turnover during an agile transition is not uncommon

They split up their test organization… However, they put the testers into the development units without any training; within three months, all of the testers had quit because they didn’t understand their new role. [CG09]

Similarly, in an agile transition we worked with, many testers left to different products because they felt they had lost their identity and did not know how to work in a Scrum team. Prevent this by developing the team’s testing expertise.

Create community of testing

Education and coaching are not the only ways to grow expertise. Open discussion and experience-sharing foster learning. One purpose of a functional unit–a test department–is to enable this learning. Without it, other means for discussion and sharing experiences are needed. For instance, by establishing a Community of Practice for testing. People interested in testing–not only those with testing as their main specialization–meet every now and then to learn from each other or discuss via a mailing list or wiki.

Test managers can play an important role in this community. They can use their expertise in testing and management and become CoP coordinators–in accordance with the lean principle of manager-teachers.

Rather than keeping the testers separate… [think about] a community of testers. Provide a learning organization to help your testers … share ideas and help each other. If the QA manager becomes a practice leader in the organization, that person will be able to teach the skills that testers need to become stronger and better able to cope with the ever-changing environment. [CG09]

Don’t have separate test automation teams

We advise organizations to invest in test automation and create a safety net of regression tests around their legacy code so that they can gradually work themselves out of the mess. They listen, and then create a separate test automation team.

Sometimes the test automation team tries to solve all world problems with their testware, and the effort produces only a lot of paper. But, sometimes we encounter a more pragmatic test automation team that actually creates testware such as an automation framework. They release every couple of months and everyone is impressed with the results.

What happens then? New functionality is implemented. Interfaces change and the automated tests fail. The development teams are upset and tell the test automation team to fix the tests. Or, the development teams comment out the tests because they do not understand them. Or, the testware is handed over to the development teams who discover it is unusable or incomprehensible and ignore it. Or… we have experienced a dozen different scenarios in organizations. It never worked.

Why? The assumption that is the creation of the testware is the difficult part and the most important thing. But other important aspects are under-appreciated:

- Creating testware requires deep understanding of the product.

- Maintenance and evolution is more effort than initial creation.

- Insights obtained during testware creation is perhaps more important than the testware itself.

- Creating testware without using it leads to complex and unusable testware.

Considering these aspects, a separate automation team causes additional complexity, the wastes of handoff, and knowledge scatter. No wonder it so often fails.

Test automation should be the responsibility of the cross-functional development teams–just as testing is also their responsibility.

There is no shortcut to learning how to automate; a separate automation team is a quick fix –and harmful in the long run.

Feature team as test automation team

A separate test-automation team has many drawbacks but also some advantages. They can create the initial test framework, produce training material, and support the teams.

How to get these benefits without the drawbacks?

A feature team can temporarily take on the role of test-automation team. Advantages:

- They have a deep understanding of the system.

- They can take a small feature so that the automation is concrete and realistic.

- The learning created during test -automation will not be lost.

- There is visibility into test automation as the items go on the Product Backlog.

All tests pass–stop and fix

Test fails?

Stop and fix it!

“What about your automated tests?” we ask product groups when we visit them. Sometimes they reply, “We have 800 automated tests of which 200 are failing right now.” This is a huge queue and causes a complete lack of transparency in the development. When automated tests fail, fix them immediately.

Have zero tolerance on open defects

Why do people insist on creating defects? They spend effort to insert a defect, then they need to search for it, prioritize it, and finally fix it. Not creating the bug in the first place would be a lot less work.

We do believe it is possible to write bug-free code . We do not believe it is easy or common. Still, focus on preventing defects.

“Zero tolerance on open defects” is a guideline used by one of our clients. If they find a defect, they fix it as soon as possible. This prevents

- effort spent on tracking many defects

- effort spent on prioritization

- delaying the learning that happens when fixing a defect

- spending extra time on fixing because the developers do not remember the code anymore

Delaying the fixing of bugs is a false economy inasmuch as they need to be fixed anyway and the cost will be higher. Moving bugs from queue to queue is fooling yourself–they are still there!

Conclusion

Testing is not what it used to be. The barriers between testing and programming have to be demolished. Testing and programming are two sides of the same activity done by the same people. The purpose of the tests changes from finding defects to preventing them by writing the specifications as tests; and from checking the implementation to driving the design. This fundamentally different perspective leads to vital changes in the way people work–and work together.

Recommended Readings

- Agile Testing , by Lisa Crispin and Janet Gregory. A great overview of the role of testing in agile development. It covers the challenges organizations face when adopting agile development and also describes the concrete role of testing during the iteration.

- Lessons Learned in Software Testing , by Cem Kaner, James Bach, and Bret Pettichord. This book describes the lessons learned from decades of experience in testing and also introduces the context-driven school of thinking in software testing.

- Agile Testing Directions , by Brian Marick. A series of blog posts wherein Brian Marick introduces the agile testing quadrants.