Feature Teams

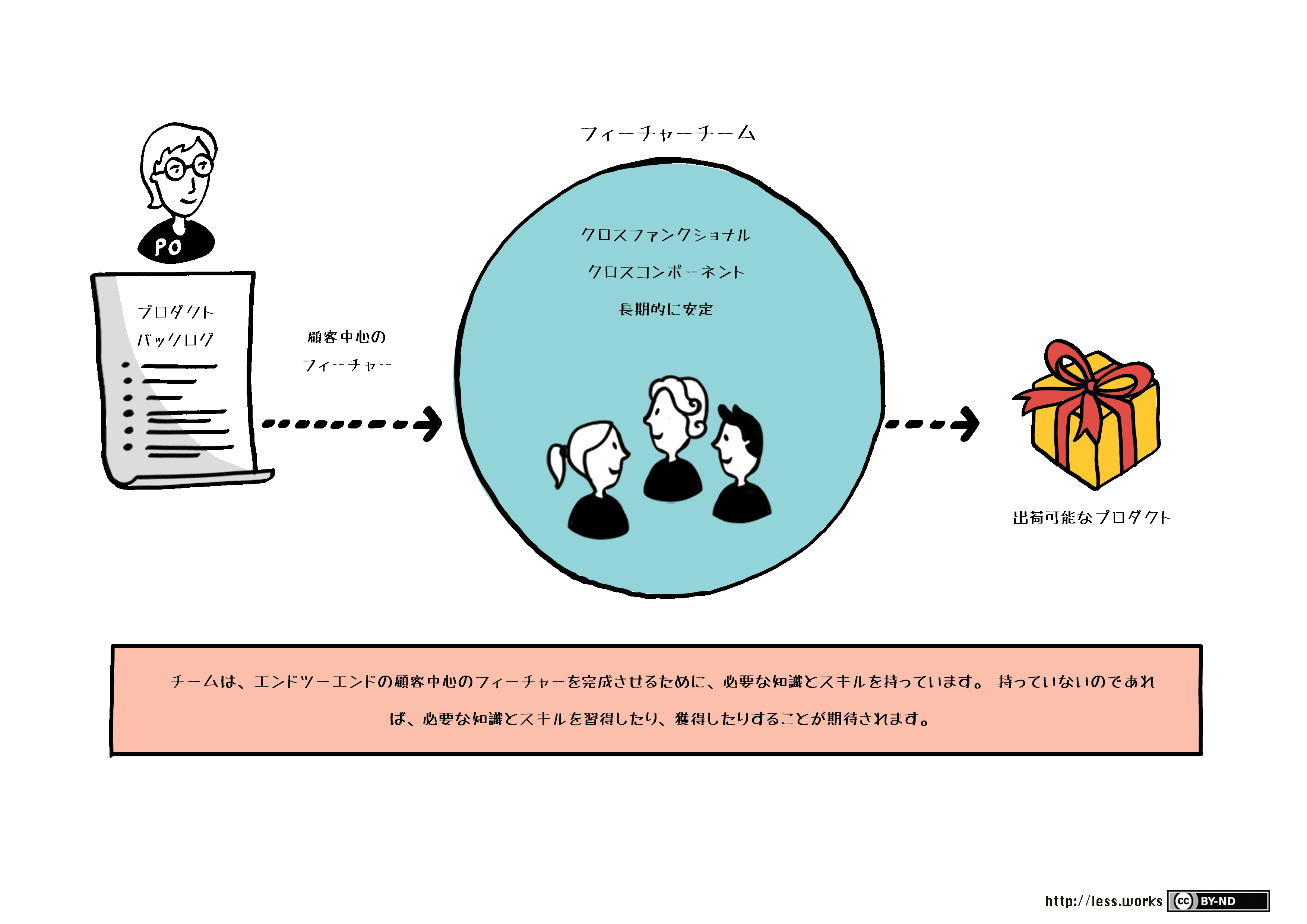

A feature team, shown in Figure 1, is a long-lived, cross-functional, cross-component team that completes many end-to-end customer features—one by one.

The characteristics of a feature team are listed below:

- long-lived—the team stays together so that they can ‘jell’ for higher performance; they take on new features over time

- cross-functional and cross-component

- co-located

- work on a complete customer-centric feature, across all components and disciplines (analysis, programming, testing, …)

- composed of generalizing specialists

- in Scrum, typically 7 ± 2 people

A feature team has the necessary knowledge and skills to complete an end-to-end customer-centric feature. If not, the team is expected to learn or acquire the needed knowledge and skill.

Applying modern engineering practices—especially continuous integration—is essential when adopting feature teams. Continuous integration facilitates shared code ownership, which is a necessity when multiple teams work at the same time on the same components.

A common misunderstanding: every member of a feature team needs to know the whole system. Not so, because

- The team as a whole—not each individual member—requires the skills to implement the entire customer-centric feature. These include component knowledge and functional skills such as test, interaction design, or programming. But within the team, people still specialize… preferably in multiple areas.

- Features are not randomly distributed over the feature teams. The current knowledge and skills of a team are factored into the decision of which team works on which features.

Within a feature team organization, when specialization becomes a constraint…learning happens.

A feature team organization exploits speed benefits from specialization, as long as requirements map to the skills of the teams.

But when requirements do not map to the skills of the teams, learning is ‘forced,’ breaking the overspecialization constraint.

Feature teams balance specialization and flexibility.

component vs. feature teams

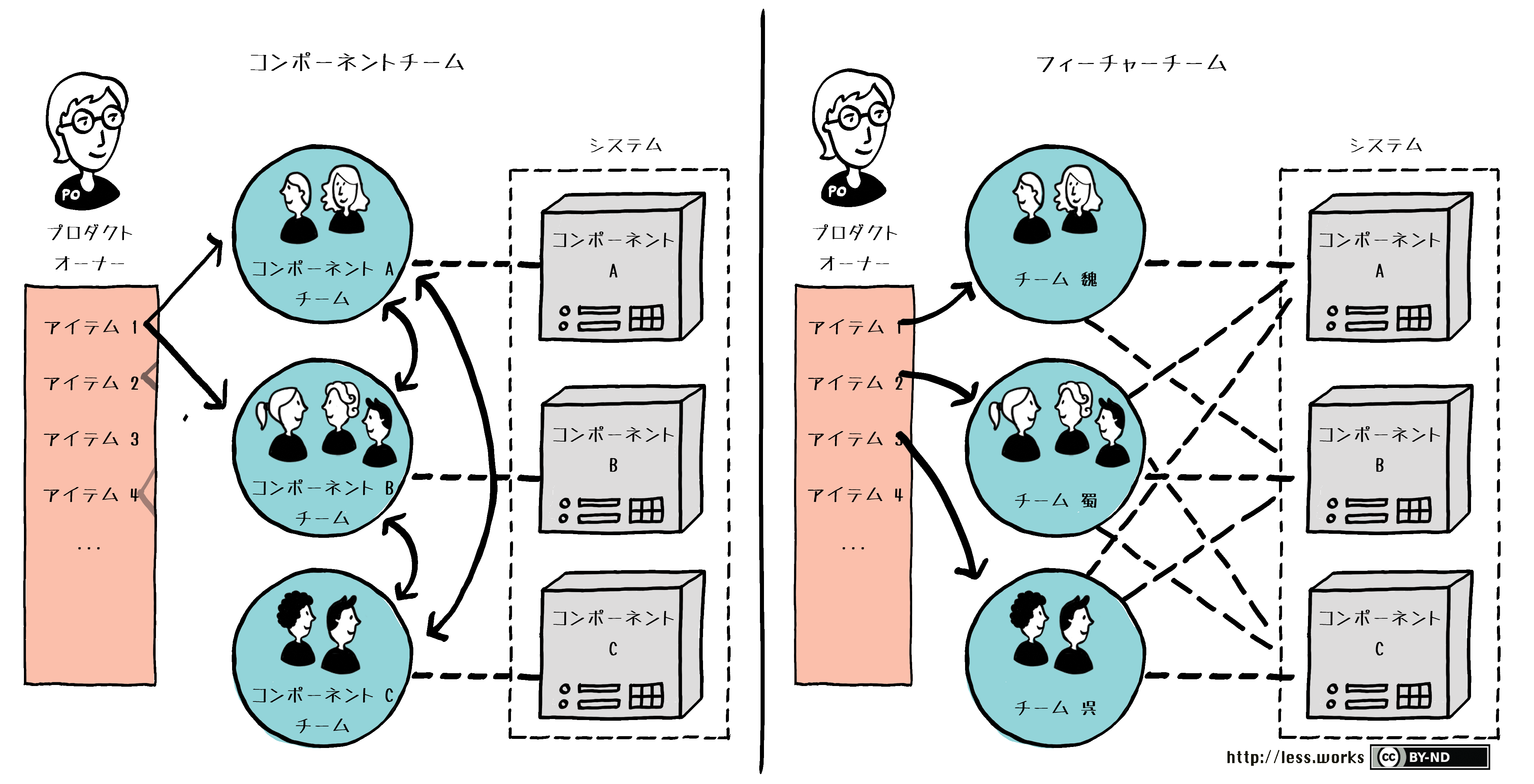

The table below and Figure 2 show the differences between feature teams and more traditional component teams.

| component team | feature team |

|---|---|

| optimized for delivering the maximum number of lines of code | optimized for delivering the maximum customer value |

| focus on increased individual productivity by implementing ‘easy’ lower-value features | focus on high-value features and system productivity (value throughput) |

| responsible for only part of a customer-centric feature | responsible for complete customer-centric feature |

| traditional way of organizing teams — follows Conway’s law | ‘modern’ way of organizing teams — avoids Conway’s law |

| leads to ‘invented’ work and a forever-growing organization | leads to customer focus, visibility, and smaller organizations |

| dependencies between teams leads to additional planning | minimizes dependencies between teams to increase flexibility |

| focus on single specialization | focus on multiple specializations |

| individual/team code ownership | shared product code ownership |

| clear individual responsibilities | shared team responsibilities |

| results in ‘waterfall’ development | supports iterative development |

| exploits existing expertise; lower level of learning new skills | exploits flexibility; continuous and broad learning |

| works with sloppy engineering practices—effects are localized | requires skilled engineering practices—effects are broadly visible |

| contrary to belief, often leads to low-quality code in component | provides a motivation to make code easy to maintain and test |

| seemingly easy to implement | seemingly difficult to implement |

The table below summarizes the differences between feature teams and conventional project or feature groups.

| feature team | feature group or feature project |

|---|---|

| stable team that stays together for years and works on many features | temporary group of people created for one feature or project |

| shared team responsibility for all the work | individual responsibility for ‘their’ part based on specialization |

| self-managing team | controlled by a project manager |

| results in a simple single-line organization (no matrix!) | results in a matrix organization with resource pools |

| team members are dedicated—100% allocated—to the team | members are part-time on many projects because of specialization |

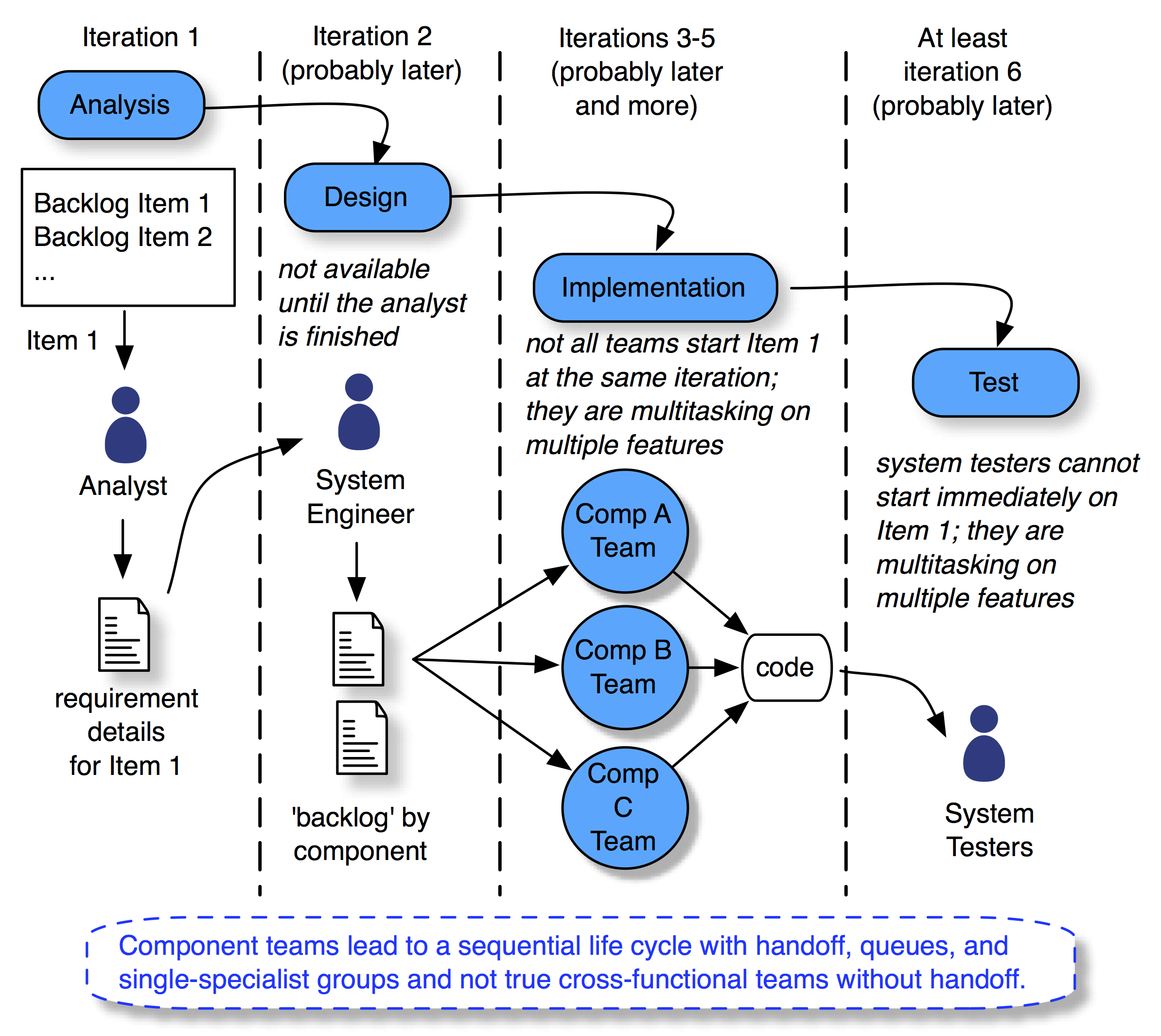

Most drawbacks of component teams are explored in the “Feature Teams” chapter of Scaling Lean & Agile Development, Figure 3 summarizes some of these.

What is sometimes not seen is that a component team structure reinforces sequential development (a ‘waterfall’ or V-model), with many queues with varying-sized work packages, high levels of WIP, many handoffs, and increased multitasking and partial allocation.

Choose Component Teams or Feature Teams?

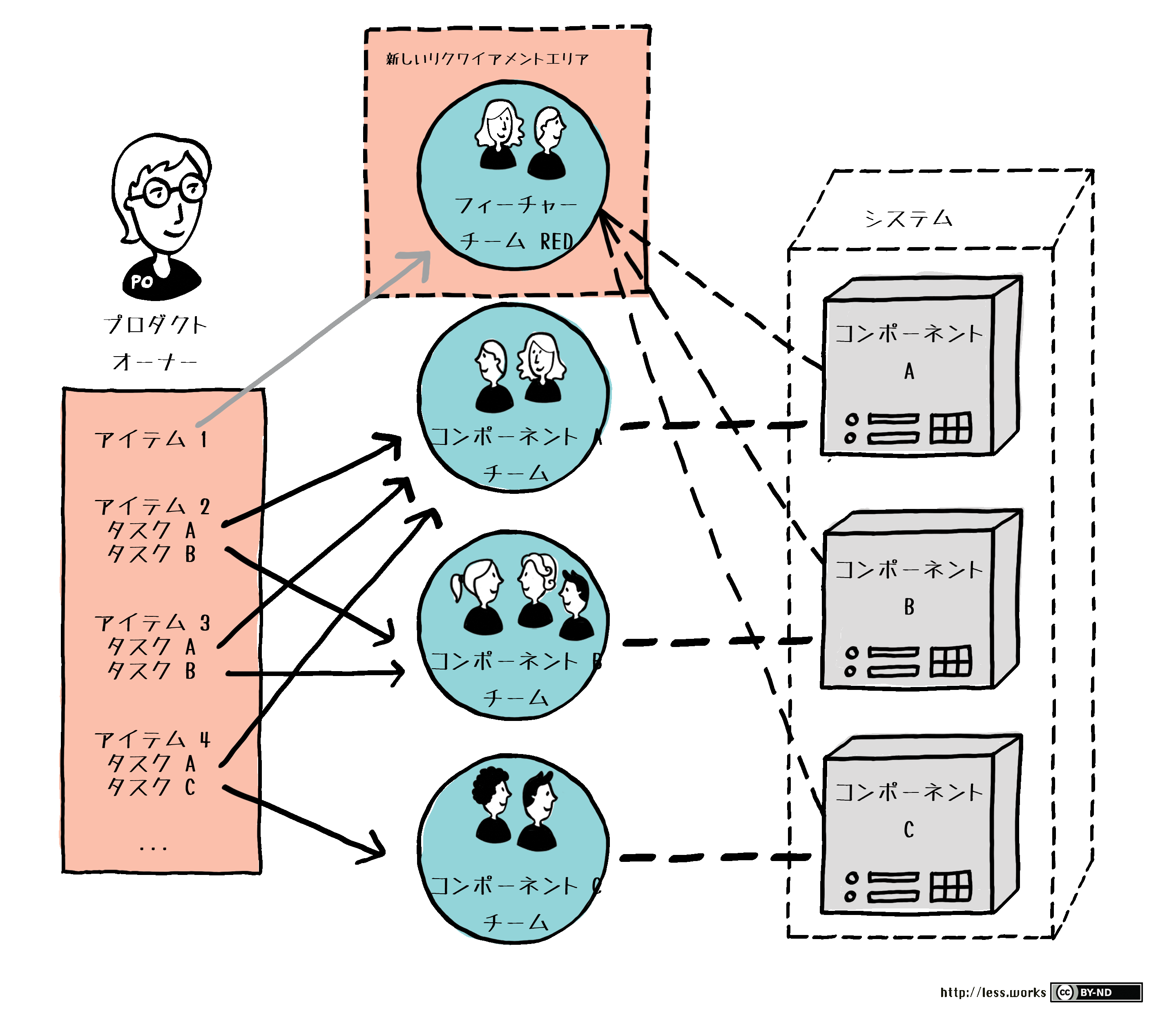

A pure feature team organization is ideal from the value-delivery and organizational-flexibility perspective. Value and flexibility, however, are not the only criterion for organizational design, and many organizations therefore end up with a hybrid—especially during a transition from component to feature teams. Caution: hybrid models have the drawbacks from both worlds and can be…painful.

A frequently expressed reason in favor of a hybrid organization is the need to build infrastructure, construct reusable components, or clean up code—work traditionally done within component teams. But these activities can also be done in a pure feature team organization—without establishing permanent component teams. How? By adding infrastructure, reusable components, or cleanup work to the Product Backlog and giving it to an existing feature team—as if it were a customer-centric feature. The feature team temporarily—for as long as the Product Owner wishes—does such work and then returns to building customer-centric features.

Transitioning to Feature Teams

Different organizations require different transition strategies when changing from component to feature teams. We have experience with many strategies that worked…and failed in a different context. A safe—but slow—transitioning strategy is to establish one feature team within the existing component team organization. After this team performs well, a second feature team is formed. This continues gradually at the speed the organization is comfortable with. This is shown in Figure 4.

Recommended Reading

- Feature Team Primer

This article originally appeared as the Feature Team Primer - Feature Teams chapter of Scaling Agile & Lean Development

This 60-page analysis of feature and component teams is also available online - Dynamics of Software Development by Jim McCarthy

Originally published in 1995 but republished in 2008. Jim’s book is a true classic on software development. Already in 1995 it emphasized feature teams. The rest of the book is stuffed with insightful tips related to software development. - “XP and Large Distributed Software Projects” by Karlsson and Andersson.

This early large-scale agile development article is published in Extreme Programming Perspectives. It is a insightful and much under-appreciated article describing the strong relationship between feature teams and continuous integration. - “How Do Committees Invent?” by Mel Conway.

This 40-year article is as insightful today as it was 40 years ago. It is available via the authors website at www.melconway.com.