Continuous Improvement Towards Perfection

A constitution should be short and obscure.

—Napoléon Bonaparte

Naturally, a group adopting LeSS brings to the table their assumptions and habits about adoption and improvement and change. Those are? Create a change vision and kick off some change projects. When the original goal (e.g., “adopt LeSS”) is apparently achieved then:

- “the change is done”, and

- the organization settles into a new status quo, until

- the next change effort surfaces, and then

- undoes the previous change.

This classic approach is like the sequential and “big batch” approach of software development where change is an exception strictly managed… by many change-control boards.

In LeSS, there is no change initiative, no change group, no change managers. In LeSS, change is continuous through experimentation and improvement and change is the status quo. When are you done successfully adopting LeSS? Never. When are you finished improving? Never.

What is perfection? There isn’t exactly a correct answer, but for example:

- the features are perfect, and profoundly delight customers; your product is awesomely popular and profitable

- you can create these features easily free of defects with almost no effort or cost

- your organization has agility; it can easily change direction with almost no friction or cost—can turn on a dime for dime

- your employees have extraordinary breadth and depth of skill and knowledge, and truly enjoy the work

That should keep you improving for awhile ;)

Continuous improvement towards perfection is one of the two pillars of Lean Thinking, also a LeSS principle. Since lean thinking—and so continuous improvement—comes originally from Toyota, some of this introduction draws on the Toyota background.

This principle of continuous improvement is based on several practices and ideas:

- Go See

- kaizen

- value and waste

- perfection challenge

- work toward flow

- respect for people

Go See

Go to the source [the place of real value work—gemba] to find the facts to make correct decisions, build consensus, and achieve goals at our best speed. [Toyota01]

We know managers in LeSS organizations that have given up their separate office (to teams, as a workshop room) and by sitting directly with the developers, have been very surprised to see and learn what’s really going on, even though they have been with their group for years.

Go See is a principle and practice not found in many management cultures. But in the internal Toyota Way 2001 it is highlighted as a primary factor for success in continuous improvement. (In Japanese the Toyota term is genchi genbutsu Go See shows up repeatedly in Toyota manager quotes, in Toyota culture and habits [LH08], and in Toyota-internal education on the Toyota Way (lean thinking).

What does it mean to practice Go See? That people, especially managers—including senior managers—don’t spend all their time in offices and meeting rooms, and don’t receive all their information via meetings, reports, email, and reporting tools. Rather, to know what is really going on and help improve (by eliminating the distortion that comes from indirect information), managers frequently go to the place of real work, stay there, and see and understand for themselves. In an interview, Toyota’s chief engineer quoted Taiichi Ohno, who insisted on managers practicing Go See at gemba:

Don’t look with your eyes, look with your feet… people who only look at the numbers are the worst of all. [Hayashi08]

Go See at gemba. What and where is gemba? Gemba does not mean the place of supporting or secondary work of accounting and so on, but the value-adding work that directly creates or delivers the product or service that the paying customer cares about. For example, the place where people are writing code, answering customer questions, etc. And gemba is not in a meeting room or office near the workers!

An example of Go See is for managers to sit for meaningful time with software developers while they are doing the work of creating code, with the aim of understanding problems and opportunities to improve, building trust, and helping.

Note that Go See is not the same as “management by walking around.” Walking around only gives superficial understanding. Go See takes time.

Kaizen

Kaizen is sometimes translated as simply “continuous improvement” but that confuses it with the broader lean pillar of “continuous improvement” and does not capture the full flavor. So, we will stick with the Japanese term.

Kaizen is both a personal mindset and a practice. As a mindset, it suggests “My work is to do my work and to improve my work” and “continuously improve for its own sake.” More formally as a practice, kaizen implies:

- choose and practice techniques/processes “by the book” that the team and/or product group has agreed to try, until they are well understood and mastered

- experiment until you find a better way, then make that the new temporary ‘standard’

- repeat forever

Step 1—Choose and practice techniques the team and/or product group has agreed to try, until they are well understood (master standardized work.) The idea is for a group to first find (hopefully) skillful baseline practices and learn to do them well. A novice team follows the Scrum description with good coaching. The group’s working agreements, such as coding standards and “definition of done” are followed. People learn to do test-driven development with plenty of practice, coaching, and good education. Step one in kaizen implies having patience through the awkward learning phase and not abandoning new techniques quickly. People need a valid baseline to improve against. And in Deming’s terminology, they need to be able to distinguish between common-cause and special-cause variability.

This step-one point of kaizen is that a person or team cannot accurately see if they need to improve or change a practice unless they have first mastered the basics, understood its subtle points, and can do it well. Have you ever seen, “Oh,

In lean thinking, standardized work does not mean conforming to centralized standards—A gross misunderstanding of lean thinking is the notion that “standardized work” means conformance to centrally-defined standards. This is such a profound mistake from the lean perspective, yet so easily misunderstood, that this point deserves special emphasis. Rather, the idea is for a team to master a baseline against which improvement experiments can be compared. This baseline—the standard—is created by the team themselves (not by a centralized group) and is ever-evolving. As Ohno said:

I told everyone that they weren’t earning their pay if they left the standardized work unchanged for a whole month. The idea was to let people know that they were responsible for making continual improvements in the work procedures and for incorporating those improvements in the standardized work. [SF09]

Share rather than enforce practices—The working-agreements or norms should not be misconstrued to mean a rigid practice to follow “until notified otherwise” or a centralized top-down ‘standard’ from a central process group that is forced on people—ideas contrary to the lean pillar of continuous improvement. Toyota people promote yokoten—spread knowledge laterally that may evolve uniquely in different locations, like a graft from a tree. Yokoten means literally to unfold or open out sideways. Spread knowledge implies a culture that emphasizes horizontal knowledge sharing, but not being forced to conform to central processes pushed top-down. Some quotes from Toyota people:

If we try to simply get everyone to the current standard you are missing opportunities to get better. You are not taking into account how times are changing. There has to be lots of flexibility in allowing creativity along the way… Standards are not developed and then communicated from headquarters to all the plants. Rigid standards will only kill kaizen… It is yokoten every time—share best practices. …We must let individuals from plants decide what they will do to fix their problems and close gaps. We cannot have someone from corporate saying you need to do X, Y, Z, because this is completely contrary to Toyota problem solving. [LH08]

By the way, communities of practice—an important element in a LeSS organization–are used to spread knowledge laterally.

Steps 2 and 3—Small, incremental, relentless change of anything. Kaizen is an on-going activity by all people (including managers) to relentlessly and incrementally change and improve practices, usually in small experiments, though large-scale system kaizen is also an option. Almost no practice, process, or existing policy is sacred—anything can go. “Challenge everything,” in the words of Toyota President Convis. Also, a kaizen culture is not one where only big improvement projects by process experts are initiated. Rather, each team does it regularly themselves.

Learn process improvement by doing–Kaizen implies, by ceaseless repetition and mentoring, people learn by themselves how to make problems visible, analyze their root causes, and improve by experimenting. And ‘failure’ of experiments is OK. The only failure in kaizen is to not continuously experiment.

Kaneyoshi Kusunoki, another student of Taiichi Ohno, and executive vice-president at Toyota, said about kaizen and management support:

A defining characteristic of the corporate culture at Toyota is that managers don’t scold you for taking initiative, for taking a chance and screwing up. Rather, they’ll scold you for not trying something new, for not taking a chance. Leaders aren’t there to judge. They’re there to encourage people. That’s what I’ve always tried to do. Trial and error is what it’s all about!

In the seminal book [Kaizen] by Masaaki Imai, he shares:

The essence of Kaizen is simple and straightforward: Kaizen means improvement. Moreover, Kaizen means ongoing improvement involving everyone, including both managers and workers. The kaizen philosophy assumes that our way of life—be it our working life, our social life, or our home life—deserves to be constantly improved.

Kaizen reflects the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) Shewhart improvement cycle (also known as the Deming cycle). In fact many people within Toyota formally know PDCA and sometimes describe what they are doing as “endless PDCA”.

Value and Waste

What to improve during kaizen? In lean thinking the answer requires an understanding of value and waste.

Value—The moments of action or thought creating the product that the customer is willing to pay for. In other words, value is defined in the eyes of the external customer. Imagine a customer was observing the work in your office. At what moments would they be willing to reach into their pocket, pull out money, and give it to you?

Waste—All other moments or actions that do not add value but consume resources. Wastes come from overburdened workers, bottlenecks, waiting, handoff, wishful thinking, and information scatter, among many others.

Improvement by Banishing Waste–After having defined value and waste, we come to a noteworthy difference in lean improvement. Other systems focus on refining existing value actions; for example, improving skill in software design. A worthy goal no doubt.

However, since there are typically few value-adding moments in the time line—maybe 5 percent—then improving those does not amount to much. But with a mountain of waste time in the process, there are big opportunities to improve the value ratio by eliminating waste.

For example, a common waste in development is the waste of work-in-progres (WIP)s, such as half-done work or intermediate work artifacts (requirement and design documents, …). There is no return-on-investment from WIP, and it can hide defects. And—key point—traditional organizations have a MOUNTAIN of WIP. So it makes little sense to focus on measuring and improving (for example) programmer efficiency by 2 percent if there is a mountain of WIP in your process.

As another example, one of the wastes is waiting or delay—customers do not pay for that. Have you ever seen the waste of waiting…

- for requirements or designs or clarification?

- for approval?

- for another development team to finish their part?

Waste Categories with Examples and Comments

Within Toyota people are educated to develop “eyes for waste.” As a learning aid, lists of non-value-adding (NVA) waste actions have been created. There is not one correct list—the point is not the categories, but to learn to see and banish waste from the customer perspective. The following product-development NVA action categories are drawn from The Toyota Way, Implementing Lean Software Development, and Lean Product and Process Development.

- Overproduction of features, or of elements ahead of the next step; duplication

- features the customer doesn’t really want

- features created and deployable, but not deployed

- duplication of data or code

- Waiting, delay—for clarification, documents, approval, components, other groups to finish something

- Handoff, conveyance, moving—giving a specification from an analyst to a developer giving code from a developer to a tester

- Extra processing (includes extra processes), relearning, reinvention, duplication—forced conformance to centralized process checklists of ‘quality’ tasks, recreating a component another developer has made

- Partially done work, work in progress (WIP)

- requirements or design documents

- code written by not tested or integrated

- Task switching, motion between tasks; interrupt-based multitasking

- interruption to handle hot defects

- multitasking on 3 projects

- partial allocation of a person to many projects

- Defects, testing/review/inspection and correction after creation of something

- testing and correction to find and remove defects from code, after the code has been created

- code reviews after the code has been created

- document reviews/inspections after the document has been created

- Under-realizing people’s potential and varied skill, insight, ideas, suggestions—are people only working to a single-speciality job title? Do people have the chance to change what they see is wasteful?

- Knowledge and information scatter or loss

- from information in separate documents

- from information handed off between single-function groups or people

- from learning that was not shared or spread

- from communication barriers such as walls between people, or people in multiple locations

- Wishful thinking (for example, that plans, estimates, and specifications are ‘correct’)—“The estimate cannot increase; the effort estimate is what we want it to be, not what it is now proposed.” “We’re behind schedule, but we’ll make it up later.”

- Blaming

Improving through Removing Waste—The focus on delivering value through waste reduction orients a lean organization toward following the baton rather than the runners. Notice that the improvement strategy is subtractive rather than additive. Rather than (for example), “What can we get the workers to do to increase utilization?”, the question is “What can we remove or stop doing?” In our consulting we have found this to be a mindset change for traditional quality-assurance people in large organizations who focus on conformance to checklists and adding activities for ‘improvement.’

Temporarily Necessary Waste versus Pure Waste—In lean thinking two types of waste are recognized:

-

Pure waste—These are non-value adding actions that in principle can and should be eliminated now; there is no law of the land or physics, or hard constraint, that prevents their elimination. For example, if a group is participating in the waste of defects with test-last and correct-last, that can be replaced with acceptance test-driven development; the test-last and correct-last process is pure waste.

-

Temporarily necessary waste–These are things we must do because of some constraint, but still correctly classify as waste. For example, banks must do “regulatory compliance” activities (mostly, in response to prior failings by the banks). These activities are required by law, but they are not value-adding actions in the eyes of the paying customer. These are called temporary wastes because some time in the future it may be possible to change things so they are no longer necessary. Regulatory laws can change for banks.

Is WIP or Inventory Always Pure Waste?—A common view among those new to lean thinking is that inventory or WIP is always pure waste and should always be eliminated. Inventories of physical things or of intangible WIP—such as requirement specifications—imply investment without profit and hidden defects. That’s not good. However, a common practice in lean improvement is to create level pull, removing variability (one of the sources of waste) in a downstream process step by inserting a small buffer of high-quality “equally sized” WIP/inventory items before that downstream step.

This is a motivation behind the idea of ‘ready’ items in Scrum—only offer items to teams for implementation that are ready in terms of clearly understood, small, hanging issues resolved, etc. Ready items can be used as a tool for leveling or smoothing the introduction of work to feature teams. A small buffer of high-quality ‘ready’ WIP items in the Product Backlog created to support level pull is an example of temporarily necessary waste introduced to address another problem…variability.

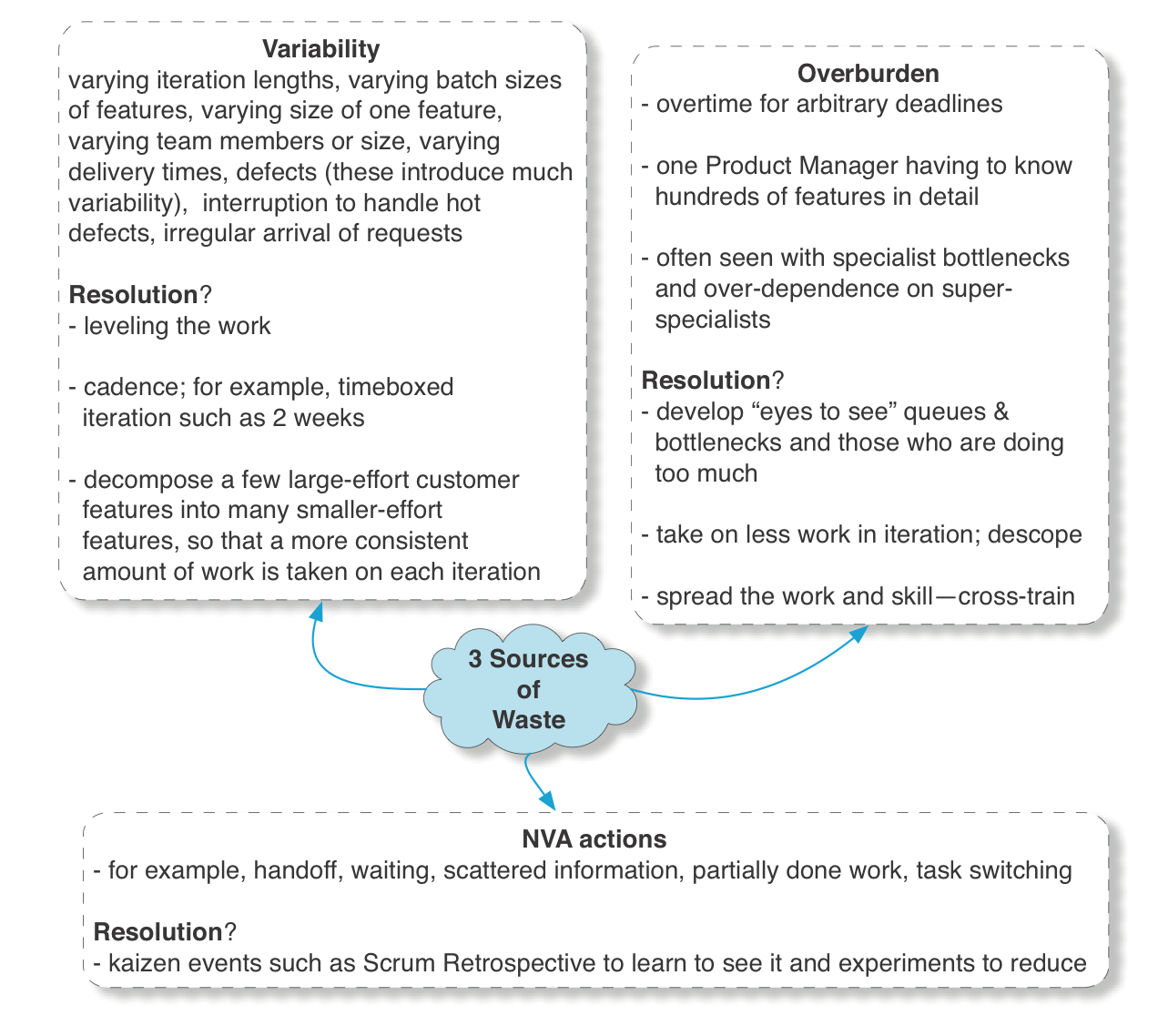

Focus on Variability, Overburden, and Non-Value-Adding Actions—In lean thinking, there are three sources of waste, illustrated and commented with resolution ideas in the following diagram. Continuous improvement involves see and eliminating variability, overburden, and non-value-adding actions.

Toyota people who observe outside attempts to adopt lean note a common mis-education about waste—the mis-education to only focus on eliminating non-value-adding actions, such as overprocessing or testing to remove defects (rather than building quality in) [LM06a]. Within Toyota, all three weaknesses are given importance, and in fact variability and overburden are viewed as frequent root causes that give rise to non-value-adding actions. For example, overburdened programmers create more defects.

Perfection Challenge

This is the third element of continuous improvement in lean thinking.

During a visit to Toyota we invited a retired engineer to dinner in Nagoya. After several rounds of sake, we asked, “What do you miss, no longer working at Toyota?” He replied, “No longer discussing perfection with people.”

We sometimes visit an organization and someone objects to the idea of changing with this argument, “We’re shipping products, making good money, and have established processes. Why should we change our practices?” We don’t think you would hear that question in Toyota. They are far from perfect and we are not suggesting simply copying them, but their culture is to have a kaizen mindset—to have high expectations and to challenge ourselves, team members, and partners to levels of skill, mastery, waste reduction, and vision far far beyond the status quo.

That’s powerful.

No Final Process

In 2001, Toyota created an internal Toyota Way booklet summarizing the lean principles. On hearing the proposed title, chairman Toyoda suggested renaming the booklet Toyota Way 2001. Why? To emphasize that there is no final process in Toyota (which would stifle kaizen), but rather, continuous improvement and change.

The implication of kaizen and spread knowledge laterally is that there is not a final or correct ‘defined’ process to follow everywhere that is communicated from a central process group. Kaizen does include learning and mastering working agreements, but they travel and evolve by the spread-knowledge-laterally yokoten model. People who have the mindset “let’s define (or buy) The Process, and then we should focus on conformance to it for a long long time.” will not be comfortable with lean thinking. To quote a Toyota CEO, “The root of the Toyota Way is to be dissatisfied with the status quo; you have to ask constantly, “Why are we doing this?” Lean and agile values—and LeSS—are based on the idea of empirical process: there is no fixed or final process or cookbook that people can follow given the reality of dynamically changing systems, and given the goal of continuous improvement. Instead, in LeSS we are left with the hard work of kaizen—to relentlessly, every Sprint—inspect and adapt the processes and create yet another “two-week experiment of techniques and processes.” In that sense, LeSS is a meta-process framework for installing and evaluating processes and practices.

In Toyota and in LeSS, the idea is to repeat this cycle forever. For example, the LeSS rules are just a simple starting point of mechanisms that will increase transparency and agility, and allow early delivery of value. They are not something to be limited by, forever. That said, kaizen starts in step one with “do the practices/processes by the book until they are mastered and fully grasped with direct experience.” That’s why in lean thinking there is the statement, “Where there is no standard, there can be no kaizen.”

Work Toward Flow

Flow suggests making value flow without delay to the customer. As a counter example, a customer request waits in a queue waiting to be approved, analyzed, implemented, reworked, or tested. That is not flow. Rather, as value is created—in products, software, information, decisions, service—it flows immediately to the customer. It is related to the follow the baton metaphor and to the goal of faster “concept to cash.” Flow is a perfection challenge; zero waste in the system and immediate continuous flowing delivery of value are profound challenges, probably never achieved. The journey is usually moving toward flow.

In lean thinking, flow is included in both the 14 principles and in the key elements of continuous improvement. Why? Because to move toward flow it is necessary to reduce batch size, cycle time, delay, WIP, and other wastes. And this has the beneficial side effect of revealing more weaknesses and waste, providing new opportunities for continuous improvement. This is an important but subtle point, expanded in the Indirect Benefits of Reducing Batch Size and Cycle Time.

Moving toward flow is associated with applied queueing theory, pull systems, and more. By understanding these, people can move the system toward flow by smaller work package sizes, smaller queue sizes, and reduction in variability. This is explored in Queueing Theory.

Pull Systems

Pull versus push—Consider a process for manufacturing and storing laptop computers. In a pure pull system no laptop is built or stored in inventory until there is a customer order. Zero inventory and zero WIP is a goal, and work is done only in response to a ‘pull’ signal from the customer. That is the key meaning of pull: Build in response to a signal from the ‘customer,’ and otherwise rest or improve. Pull examples? Printing just the twenty-book order or preparing just one restaurant dish.

But a pull system goes deeper than that—the ‘customer’ is not just the final customer. Rather, in a multi-stage process with an upstream team doing partial work before a downstream team, a downstream team is the customer to their upstream team . In a pure pull system the upstream team does not create anything unless pulled from downstream request.

On the other hand, in a push system , one speculatively builds and stores laptops in the hope of orders, and then tries to push them to customers. In a multi-stage process, upstream teams create an inventory of partially done work for downstream teams. Any kind of speculative inventory—pizzas, big detailed plans, books, specifications for many features whose value is uncertain—are related to push systems.

Resource management strategies that focus on high utilization of workers—a focus on watch the runners rather thanwatch the baton—create an environment in which people will create a large inventory of things (requirements, designs, code) in a push model.

Expose defects—If you only create one thing in response to pull from a ‘customer’ request (in this context, your customer is anyone downstream) and the customer consumes it quickly, any defects in that one thing—created either by accident or design–are quickly discovered. That can lead to further systemic improvement if people have “stop and fix” mindset. On the other hand, in push systems, defects are hidden in an unconsumed inventory (of requirements, code, …). For example, pushing a large batch of requirements will delay the discovery of misunderstandings or problems, because it is a long time before they are implemented and evaluated (as running software) by a customer.

Decide as late as possible—In pull systems, you do not decide early, quite the opposite—you “decide as late as possible” and “commit at the last responsible moment”. In this way, you have the most information to make an informed decisions. You do not waste resources making unnecessary inventory or early decisions that will have to—or at least should—change in response to discovery.

Small batches can lead to radical improvement—A pull system implies smaller batches in frequent short cycles. Using the old large-batch push-based processes (based on economies-of-scale thinking that avoided change), more short cycles may increase overall overhead or transaction cost , and hence be viewed as inefficient. The way out of that conundrum is an out-of-the-box radical improvement in processes that can embrace change and small batches efficiently. This is a secret behind Toyota’s efficiency—pull systems with small batches combined with kaizen drive new ways of working that lower the transaction cost of a process cycle. This improvement dynamic is explored in the Indirect Benefits of Reducing Batch Size and Cycle Time.

Thus, in several ways, pull systems support moving towards flow.

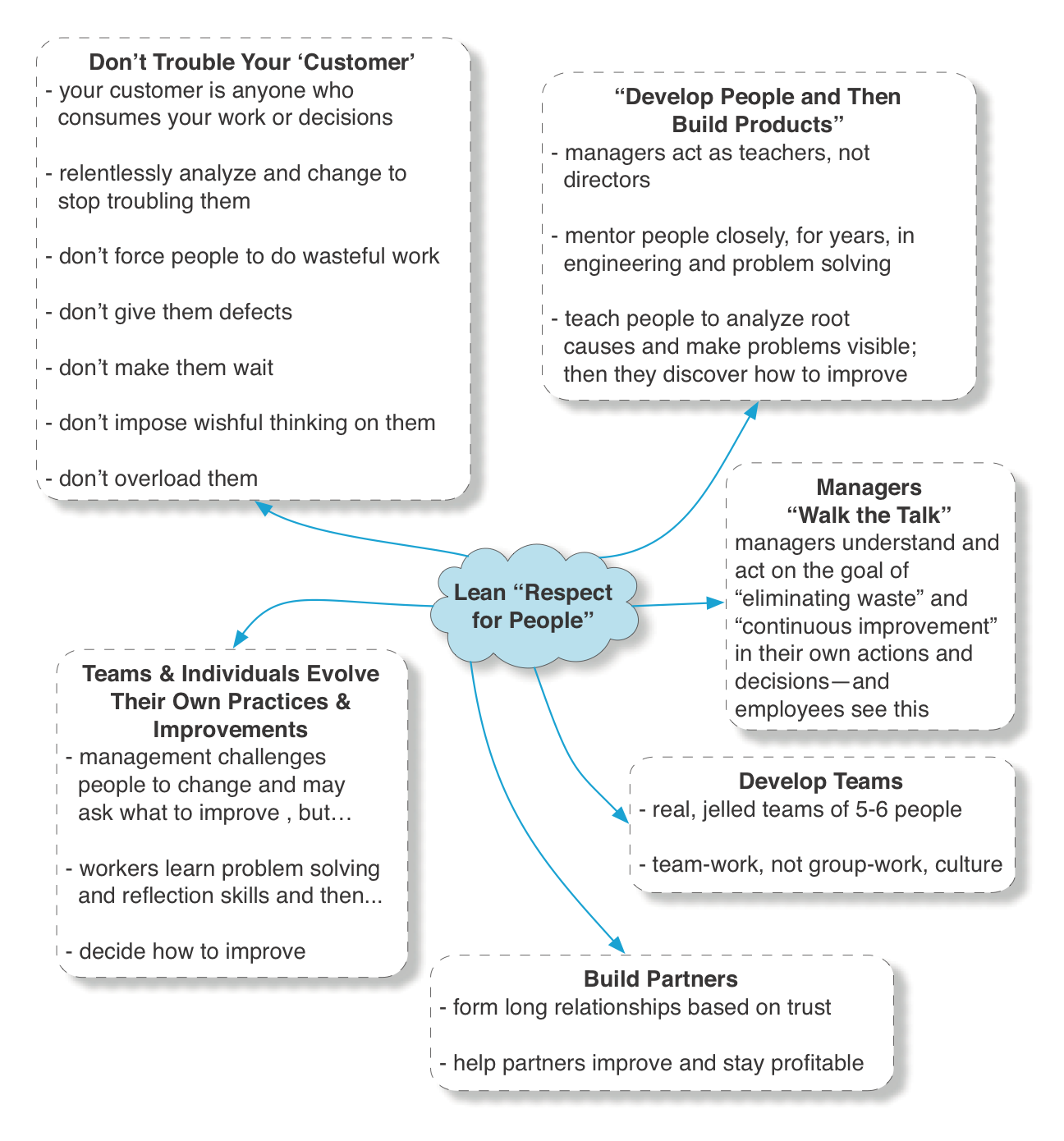

Respect for People

Respect for people sounds nebulous, but includes concrete actions and culture within Toyota. They broadly reflect respect for and sensitivity to morale, not making people do wasteful work, real teamwork , mentoring to develop skillful people, humanizing the work and environment, safe and clean environment (inside and outside of Toyota), and philosophical integrity among the management team.

In terms of continuous improvement, it includes not eliminating jobs because of improvement. Job safety is an important principle at Toyota. If people feel that improvement will lead to the end of their employment, what do you think will happen? However, job safety is not the same as role safety or position safety. Improvement may mean the elimination of overhead or single-function roles, but in a lean culture, new roles are then found for employees.

Respect for people also includes fostering a work culture and morale consistent with research into workplace satisfaction and increased motivation—which will support continuouus improvement. This includes self-directed work, opportunities for challenge and mastery, and a sense of purpose. In LeSS there is a focus on self-organizing teams (self-directed work teams), becoming multi-skilled within a cross-functional team, and connecting directly with real customers and being closer to the business. This is consistent with the research in greater potential for motivation.